Uganda - where security forces may be more deadly than coronavirus

- Published

Eric Mutasiga's mother, Joyce Namugalu Mutasiga, has to support his family after he was killed by police

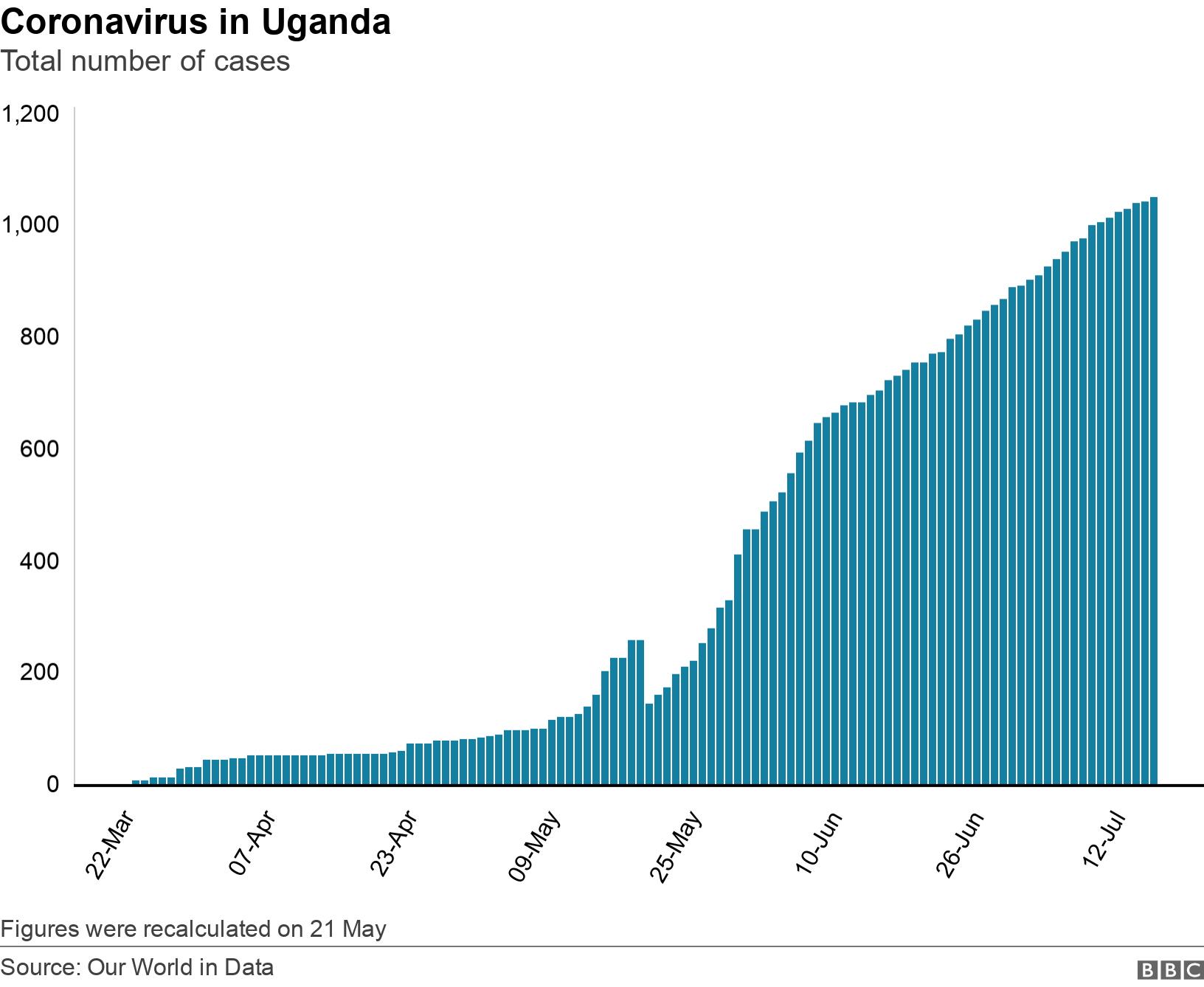

In Uganda, at least 12 people have allegedly been killed by security officers enforcing measures to restrict the spread of coronavirus, while the country has only just confirmed its first death from Covid-19. Patience Atuhaire has been meeting some of those affected by the violence.

Joyce Namugalu Mutasiga speaks to me as she fries small pancakes, known as kabalagala, over a woodfire, her words coming out in short, crisp sentences punctuated with long silences.

"Somebody is moving away from you and then you shoot him? At least they would have said sorry, because his life will never be back, and now I am going to struggle with the children," she says, straining to bottle up her emotions.

The 65-year-old is now the main bread-winner for a family of eight.

Mrs Mutasiga wants the police to apologise over the death of her son

Two of her grandchildren, aged three and five, too young to grasp the full scale of what has befallen them, run across the yard pointing to a car in the yard: "Take a photo of daddy's car!"

In June, nearly three weeks after he was reportedly shot in the leg by a Ugandan policeman, Eric Mutasiga died from his wounds. His last moments were in an operating theatre in the country's Mulago Hospital, according to his mother.

The 30-year-old headteacher was one of those allegedly killed by security forces enforcing a coronavirus lockdown.

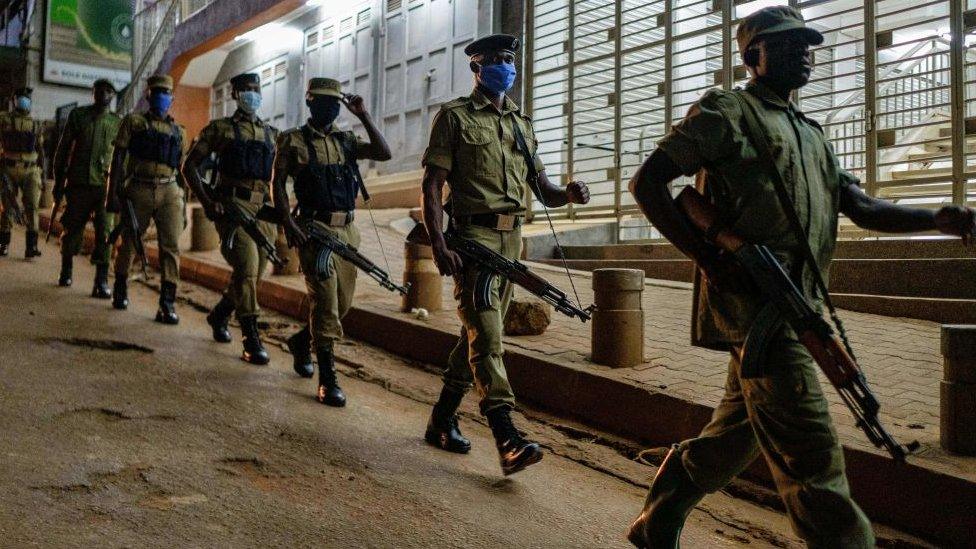

Members of the security forces have been enforcing the lockdown measures

The killings are believed to have been at the hands of policemen, soldiers and members of an armed civilian force called the Local Defence Unit (LDU).

Since March, they have been jointly manning roadblocks to ensure that people stick to the control measures, including a ban on motorcycle taxis (known locally as boda bodas) and a dusk-to-dawn curfew.

Many Ugandans are wary as they approach these roadblocks not knowing what might happen, but on 13 May trouble came to Mr Mutasiga's home.

As well as running the Merrytime Primary school, the father of three had a small shop next to his home on the edge of Mukono, about an hour's drive east of the capital, Kampala.

On that Wednesday, policemen and members of the LDU were arresting people found breaking the lockdown rules by working after 19:00.

'You didn't train me'

Mr Mutasiga's employee, a young man working at the chapati stall outside the shop, had just been detained.

"I begged [the policemen] to forgive him. The two officers debated amongst themselves whether to let him go," the headteacher later explained to local journalists.

Then, as people gathered round, things got heated.

"One of the policemen started to say I wasn't the one who trained him. He said he could even shoot me.

"As I turned to leave, [one policeman] shot in the air. I turned to see what happened, and saw him aim directly at me.

"The bullet went right into my left leg and I fell. They got on their motorcycle really quickly and rode away."

He made those comments as he was being wheeled into hospital - the police have not verified his account.

Some family members have suggested we go to court. But the police have not revealed the shooter's identify, so who would I sue?"

His family had hoped that he would make a full recovery.

"We stayed in hospital awaiting surgery, but every time we asked, the health workers told us that the wound was bad, they couldn't operate," his mother says.

Mr Mutasiga was eventually taken to the operating theatre on 8 June where he died, she adds.

The death certificate shows that he died directly from gunshot wounds.

Mrs Mutasiga stares at the ground, taking a moment to compose herself.

She feels let down by the entire government system, saying: "Some family members have suggested we go to court. But the police have not revealed the shooter's identify, so who would I sue?"

Farida Nanyonjo is angry.

Her brother, Robert Senyonga, died after being beaten.

Around midday on 7 July, she received a call from his employer. She was told that she had to get to the eastern city of Jinja fast, as Mr Senyonga had been repeatedly struck by the butt of a gun wielded by someone believed to be from the LDU for riding a motorcycle.

You may also be interested in:

The beating left the 20-year-old, who worked as a farm manager with multiple fractures to the skull.

Ms Nanyonjo got to him late at night and then returned with him to the capital, where he was referred to hospital.

"We made it to Mulago at about 2am, and spent the rest of the night on the ward floor. I approached a medical worker for help, but was asked for money. He was finally given a bed in the morning," she says.

It took a lot of haggling, and a couple of days, before Mr Senyonga could be scheduled for surgery. And by then, it was too late.

'Died in my arms'

"I am extremely angry. They beat him, but even the top hospital in the country could not give him proper medical care," Ms Nanyonjo says.

"My brother died in my arms."

For this family, the void left by their departed will be impossible to fill.

The LDU earned notoriety in the early 2000s when it was first created. Its personnel were accused of carrying out extrajudicial killings or of turning into gunmen for hire.

In the end it was demobilised. Ugandans were therefore apprehensive when it was revived in 2018.

Recruitment for the Local Defence Unit attracted huge interest in 2018

Critics say the force puts guns in the hands of young, poorly trained people who are unable to reduce the tension in a confrontation.

The army has now withdrawn all LDU personnel from deployment, for retraining.

President Yoweri Museveni and other senior officials have condemned the reported attacks but when the BBC contacted the various security agencies implicated, none of them wished to give us a statement in response to the allegations.

Rights groups argue that the problem is systemic.

"We've found that security forces have been using Covid-19 and the measures put in place to prevent its spread as an excuse to violate human rights," says Oryem Nyeko, a researcher for Human Rights Watch.

But these problems have been known for many years, he says, and "we need to explore reforming a system that emboldens people to commit abuses".

Families say the judicial process is often too convoluted to navigate, but there have been successful prosecutions in two cases in the last five months. One involving a soldier and the other a member of the LDU.

The soldier who killed Allen Musiimenta's husband was jailed by a military court for 35 years after being found guilty of murder four days after the incident.

But she is not satisfied.

"The soldier got his punishment, but I won't get my husband back," Ms Musiimenta says.

Benon Nsimenta, who was due to be ordained as a reverend in November, was gunned down on a highway in the western town of Kasese on 24 June.

He and his wife had set off for their village home on a motorbike. They had a document from a local councillor indicating that the vehicle was theirs and not a motorcycle taxi.

"The soldiers who stopped us didn't even take a minute to ask questions. One of them crossed the road, raised his gun and shot my husband in the neck," Ms Musiimenta says.

"We did our family projects together, talked through everything. We made plans for our children's future. How I am supposed to pay for their education by working our small farm?" she trails off, overcome with emotion.

Football coach Nelly Julius Kalema survived his alleged brush with the security forces - but only just.

On 8 July he was rushing a friend's sick girlfriend, Esther, to a clinic on a motorcycle. It was already curfew time.

You may also want to watch:

'The police are killing us, not coronavirus'

They were allowed through a roadblock, but then some people on a motorcycle, who he says were policemen, waved them down.

Mr Kalema says he asked if he could find a safer place to stop just ahead. He says one man took out a baton and hit Esther hard on the neck. She screamed, and fell.

"I lost balance and rammed into a concrete slab, on which I hit my head," he says, lying in a hospital bed.

The accident left him with a deep cut on the head, the scalp hanging by a few inches, that had to be stitched back. Esther survived with a broken leg and had to undergo surgery.

Nelly Julius Kalema's wound on his skull can be clearly seen

The police declined to comment on his allegations.

When we met, Mr Kalema had been in hospital for nearly a week, his head constantly throbbing.

"I have been lying here thinking I shouldn't have to feel lucky, because I had no fault in the accident. How many of us must die or be maimed before the security forces change their methods?" he wonders.

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the coronavirus pandemic

GLOBAL TRENDS: Where are cases rising and falling?

TRACKER: Coronavirus cases in Africa

- Published15 July 2020

- Published6 November 2018

- Published14 June 2020