Genetic impact of African slave trade revealed in DNA study

- Published

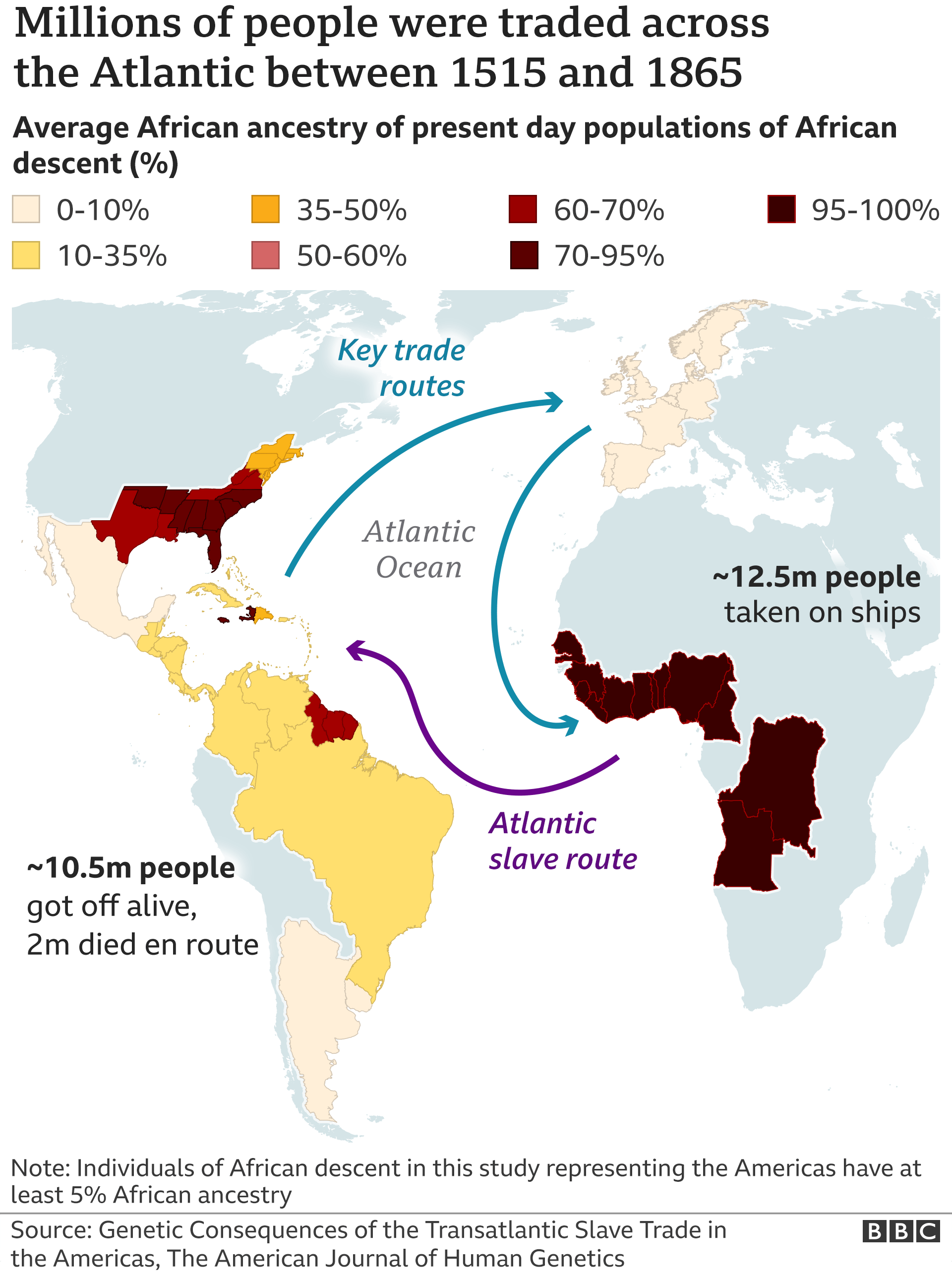

More than 12 million Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic to work as slaves

A major DNA study has shed new light on the fate of millions of Africans who were traded as slaves to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries.

More than 50,000 people took part in the study, which was able to identify more details of the "genetic impact" the trade has had on present-day populations in the Americas.

It lays bare the consequences of rape, maltreatment, disease and racism.

More than 12.5m Africans were traded between 1515 and the mid-19th Century.

Some two million of the enslaved men, women and children died en route to the Americas.

The DNA study was led by consumer genetics company 23andMe and included 30,000 people of African ancestry on both sides of the Atlantic. The findings were published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, external.

Steven Micheletti, a population geneticist at 23andMe told AFP news agency that the aim was to compare the genetic results with the manifests of slave ships "to see how they agreed and how they disagree".

While much of their findings agreed with historical documentation about where people were taken from in Africa and where they were enslaved in the Americas, "in some cases, we see that they disagree, quite strikingly", he added.

Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo creates sculptures of slaves to immerse people in their experience.

The study found, in line with the major slave route, that most Americans of African descent have roots in territories now located in Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

What was surprising was the over-representation of Nigerian ancestry in the US and Latin America when compared with the recorded number of enslaved people from that region.

Researchers say this can be explained by the "intercolonial trade that occurred primarily between 1619 and 1807".

They believe enslaved Nigerians were transported from the British Caribbean to other areas, "presumably to maintain the slave economy as transatlantic slave-trading was increasingly prohibited".

Likewise, the researchers were surprised to find an underrepresentation from Senegal and The Gambia - one of the first regions from where slaves were deported.

Researchers put this down to two grim factors: many were sent to work in rice plantations where malaria and other dangerous conditions were rampant; and in later years larger numbers of children were sent, many of whom did not survive the crossing.

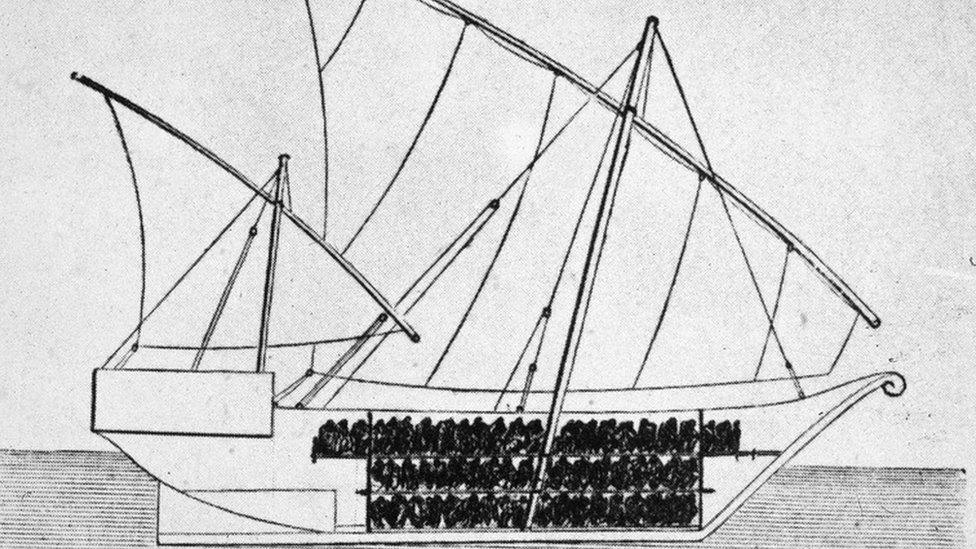

Some two million people did not survive the horrendous conditions aboard ship

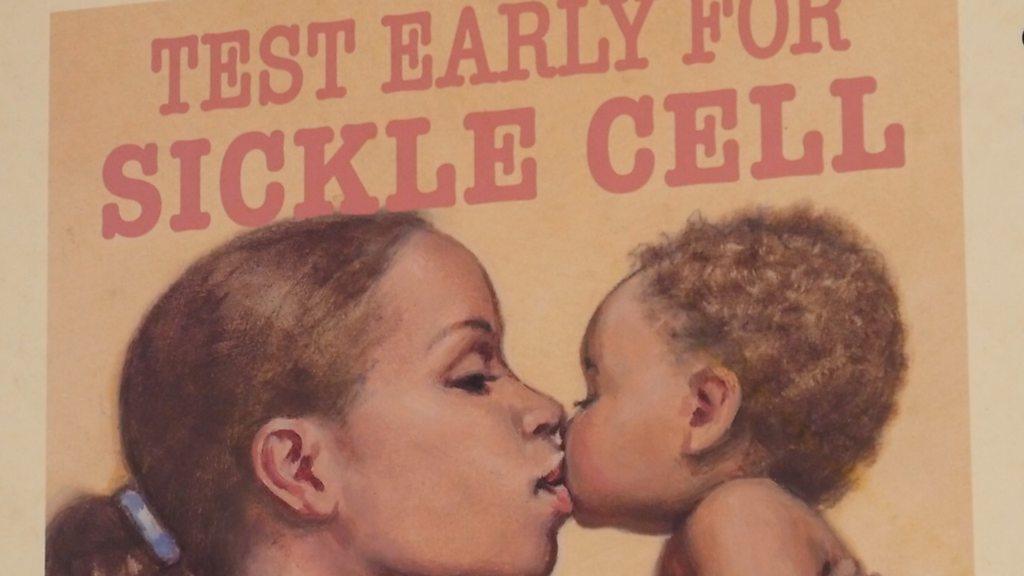

In another gruesome discovery, the study found that the treatment of enslaved women across the Americas had had an impact on the modern gene pool.

Researchers said a strong bias towards African female contributions in the gene pool - even though the majority of slaves were male - could be attributed to "the rape of enslaved African women by slave owners and other sexual exploitation".

In Latin America, up to 17 African women for every African man contributed to the gene pool. Researchers put this down in part to a policy of "branqueamento", racial whitening, in a number of countries, which actively encouraged the immigration of European men "with the intention to dilute African ancestry through reproduction".

Although the bias in British colonised America was just two African women to one African man, it was no less exploitative.

The study highlighted the "practice of coercing enslaved people to having children as a means of maintaining an enslaved workforce nearing the abolition of the transatlantic trade". In the US, women were often promised freedom in return for reproducing and racist policies opposed the mixing of different races, researchers note.

What do we do with the UK's symbols of slavery?

The Black Lives Matter movement has shone a light on the damaging legacy of colonialism and slavery on African Americans and other people of African heritage around the world. Statues of colonial-era slave traders have been pulled down as protesters demand an end to the glorifying of symbols of slavery.

- Published24 August 2019

- Published19 July 2020

- Published31 October 2019

- Published10 July 2020

- Published11 June 2020

- Published18 June 2020