Coronavirus in South Africa: Why the vuvuzelas fell silent

- Published

It's mid-winter here in South Africa's main city of Johannesburg. The other morning, I put on a woolly hat and scarf to take the dog for a walk. My son came with me, in a T-shirt and flip-flops.

As it happens, we were both correctly dressed.

South African winters are strictly cloudless affairs. For months, here on the high plains in the centre of the country, it is magnificently warm in the sunshine and bone-chilling in the shade.

And yes, there is a metaphor lurking there.

This is, after all, a nation of seemingly irreconcilable extremes. Of hunger and excess. Kindness and corruption. A precarious, miraculous, juggling act of a country that somehow wobbles on.

Swift action

Enter, the coronavirus. At first South Africans seemed to rise, collectively, to the occasion.

Back in March, the government introduced some of the toughest lockdown restrictions in the world.

Borders and schools slammed shut. The economy duly ground to a halt. Even the sale of alcohol was banned.

People were told to stay at home, to self-isolate, indefinitely. Easy enough in the suburbs. Not so convenient for millions living in tin shacks and in poor, over-crowded townships.

But somehow, it worked. The infection rate dropped dramatically.

Coronavirus in South Africa: A day in the life of a contact tracer

Every night you could hear the blare of vuvuzelas - as people honked their plastic horns in support of doctors and nurses.

Even the alcohol ban seemed bearable. It led to a dramatic drop in hospital casualty admissions. And besides, there was always home-brewed pineapple beer to try out.

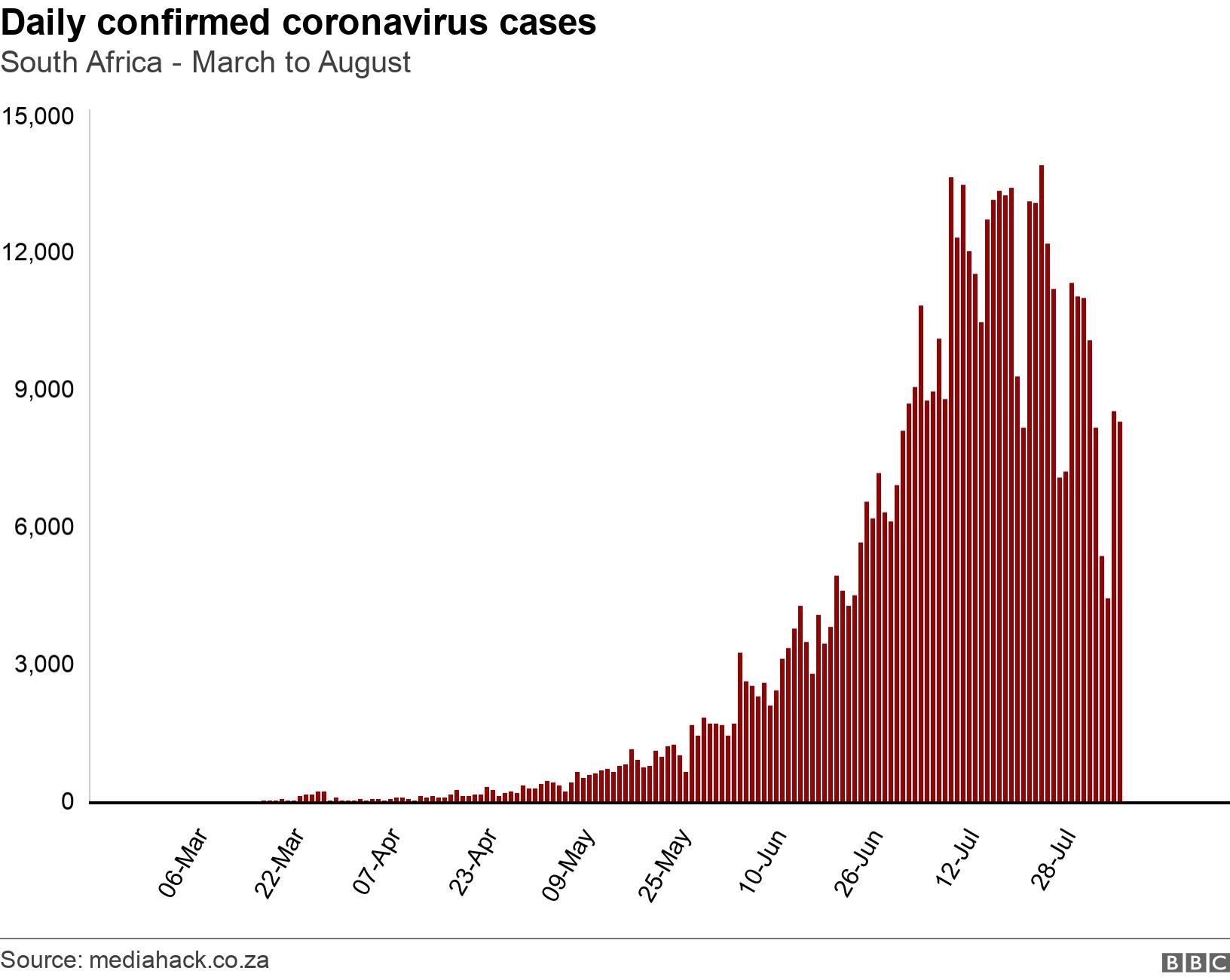

But four months later - with the lockdown eased to help revive the economy - we are now in the thick of the pandemic.

Over half a million infections. And the public mood has soured.

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30

The vuvuzelas have fallen silent. Hunger and unemployment are soaring. Listless men drift through the suburbs, begging for food.

The alcohol ban is being challenged, indignantly, in court, and entirely ignored by most people, who simply buy their booze from a thriving black market.

And above all, a fleeting sense of national unity is being whittled away, not so much by frustration, or impatience, but by the obscene corruption of South Africa's political class.

PPE inflation

It's been a problem here for years.

A bloated, politicised civil service feasting on government contracts. Using friends and family to bid for lucrative tenders.

Looting the state with almost total impunity. Increasingly, the corruption has come to seem not like an aberration, a flaw in the system, but rather the system itself.

Many South Africans seem to believe their president is an honourable man. But his latest announcement on looting was greeted with hollow laughter

So perhaps it was inevitable, when the government began pumping extra billions into the health sector - for PPE, medicine, ventilators - that some of that money would go missing.

But still, how do you explain a 900% mark-up for surgical masks?

Or a councillor stealing food parcels meant for the poor? Or contract after contract going into the pockets of politicians' all-too-well-connected sons and daughters?

President Cyril Ramaphosa recently went on television here to lash out against the crooks who were profiting from disaster.

He called them a pack of hyenas circling wounded prey. And he promised this would be a turning point, that bold, decisive action would be taken.

You may also be interested in:

Many South Africans seem to believe their president is an honourable man. That he wants to end the looting.

But his latest announcement was greeted with, at best, hollow laughter.

The governing African National Congress (ANC) has been promising a clean-up for decades.

The party will renew itself, while still in power, we're told. Which other party has ever pulled off that little trick?

Heroic medical staff

But here's the thing.

For all the miseries I've seen here - these past few weeks in particular - the weary doctors angry that they have no proper masks, grieving families convinced their relatives died unnecessarily, South Africa is still doing a relatively impressive job at defeating this virus.

The upward infection curves are starting to climb back down in most provinces. The death rate appears to have stayed surprisingly low.

Out of sight - cameras are strictly forbidden in Covid-19 wards here - heroic medical staff are managing, in a very South African way, to create some order out of chaos.

And yes, we're all wearing our masks here in public. Almost everyone. Almost everywhere. No complicated exemptions. No real argument. It just feels like basic common sense.

A few days ago, I stood in a vast graveyard on the edge of the tough, troubled city of Port Elizabeth. Cows strolled lazily between the headstones.

A series of hurried burials were taking place, 15 minutes apart.

Strict rules have to be observed for funerals

I thought, briefly, about this country - this continent's - capacity to absorb hardship, to plough on.

And then I watched another group of mourners climb out of a minibus, and soon a snatch of song wafted over towards me.

A little muffled by the masks. But strong, harmonious, hopeful. Rising up into another impossibly blue sky.

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the coronavirus pandemic

GLOBAL TRENDS: Where are cases rising and falling?

TRACKER: Coronavirus cases in Africa

- Published27 July 2020

- Published31 May 2020

- Published9 July 2024