Letter from Africa: Why Kenyans are no longer cheering their constitution

- Published

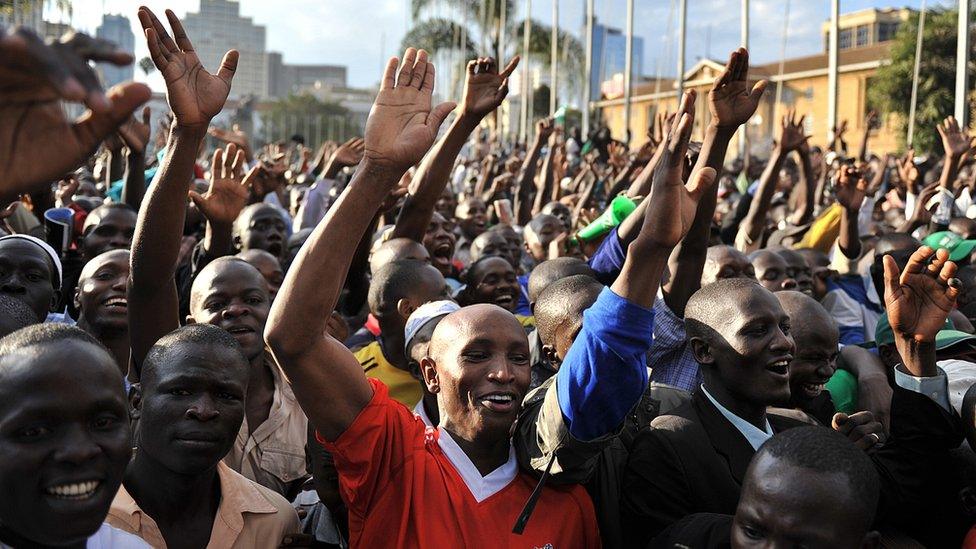

Many Kenyans were jubilant when the constitution was adopted a decade ago

In our series of letters from African journalists, Waihiga Mwaura looks at what has changed in Kenya 10 years after it adopted a new constitution intended to reform how the country was governed and reduce ethnic tensions.

There are many lessons from George Orwell's famous book Animal Farm - the most poignant being that the animals who rebelled against their human farmer hoping to create an equal society ended up being disappointed by what came next.

With the bells of independence chiming across the continent around 10 years after that classic was written, there was great hope that newly achieved African self-rule would lead to the equitable distribution of resources.

Kenya's presidents until August 2010 - from right to left Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel arap Moi and Mwai Kibaki - had been all-powerful

Several decades on that expectation was replaced by disillusion as local oppressors often took the place of the expelled colonial "masters".

This is why Kenyans were so jubilant on 27 August 2010 when a new constitution was adopted.

In the words of former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, the new laws marked the culmination of "almost five decades of struggles that sought to fundamentally transform the backward economic, social, political, and cultural developments in the country".

Imperial-like powers

What changes did the 2010 constitution usher in?

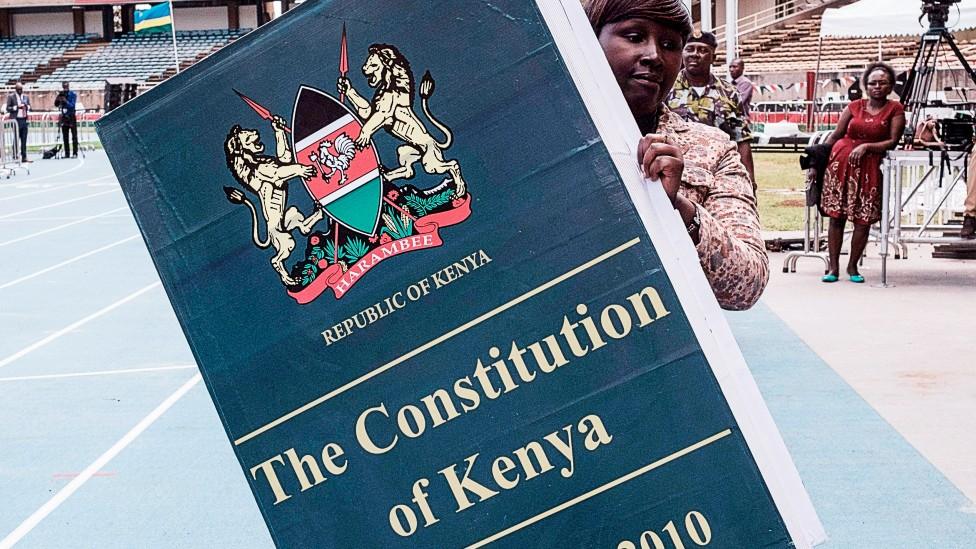

A huge ceremony attended by regional presidents was put on to ratify the new constitution

Well, previously the president operated with imperial-like powers controlling the three arms of government.

He appointed and sacked judges.

He determined the calendar of parliament and could have as many ministers as he liked.

You get the picture.

Kenyans were clear in terms of what they wanted.

They were keen to see clear a separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary.

They wanted their rights more definitively enshrined in the constitution, they wanted gender equality and they wanted the devolution of resources - away from central government to the 47 counties that were created.

'Too progressive'

So a decade on, it has been a time of reflection, looking back at the gains made - like more respect for human rights - but also at the missed opportunities.

You may also be interested in:

Inside the world of Kenya’s ‘killer cop’

And - according to an Infotrak poll commissioned by several civil society organisations, including Amnesty International Kenya - the views are mixed.

Only 23% of Kenyans are satisfied with how it has been implemented and 77% are either dissatisfied or disinterested.

Kenya's Chief Justice David Maraga recently said: "In my view the constitution of Kenya is one of the best constitutions in the world, if only we could implement it."

Senior lawyer Ahmednasir Abdullahi believes the problem is that the constitution is just too progressive for the political elite, saying they have only rolled out what is convenient to them.

One of the most striking failures can be seen in the sea of male faces in parliament - the requirement that not more than two-thirds of MPs be of the same gender has clearly not been implemented.

Many Kenyans feel the constitution has done little to end corruption

The judiciary says its funding is not in line with what was promised in the constitution.

And the executive and judiciary have certainly not seen eye to eye since the Supreme Court annulled the August 2017 election over irregularities.

When the Supreme Court was due to hear another case seeking to delay the rerun in October 2017, not enough judges turned up - one was unable to come as her bodyguard had been shot by gunmen earlier in the week - meaning the vote, boycotted by the opposition, went ahead as planned.

Judges also accuse the executive of regularly flouting court orders.

Poorer counties are still poor while a bill is languishing in parliament that would give them access to a $240m (£182m) fund for development projects.

Elections in 2017 again saw clashes that polarised the nation

The much-vaunted land commission that was to review past abuses has had little impact as it has been dogged by leadership problems.

Corruption is still a major issue - with Kenyans currently focused on the alleged theft of millions of dollars meant for the purchase of medical supplies to combat the Covid-19 pandemic that has turned into a vicious political battle.

And there is a concern that the constitution did not satisfactorily ensure the independence of the police.

'Building bridges'

So is there a way forward?

Some, including the leader of the opposition ODM party, Raila Odinga, who served as prime minister in the government of national unity that brought in the constitution after deadly post-poll violence, feel some of the laws need amending.

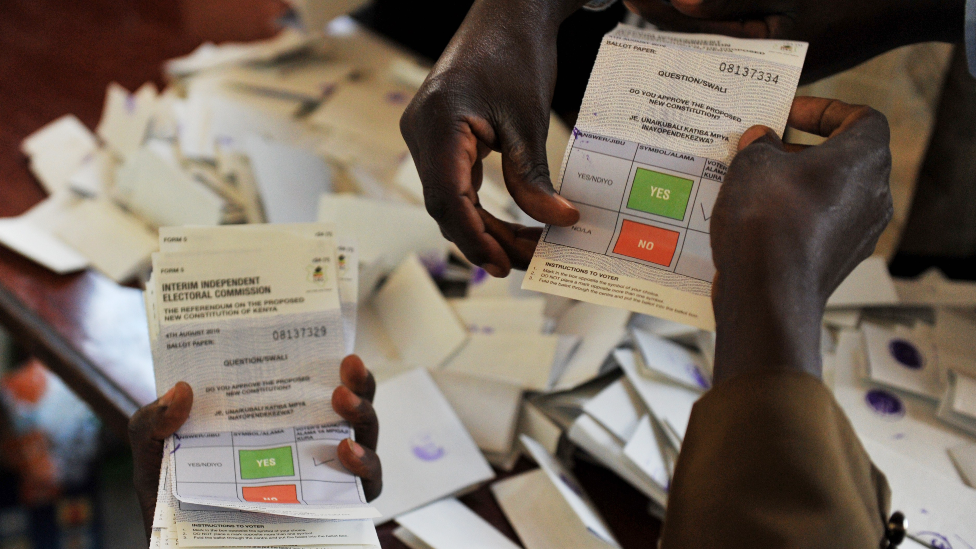

In the August 2010 referendum, 67% voted in favour of the new constitution

He has joined forces with President Uhuru Kenyatta to champion change under an initiative dubbed "Building Bridges".

The two rivals kissed and made up - metaphorically - two years ago to end tensions following another disputed, deadly and divisive election season.

They agreed to put together a team to find a way to end such instability looking at nine issues - including ethnic antagonism, corruption and devolution - thought to be among the greatest challenges since the country became independent in 1963.

And this taskforce is expected to release its final report soon.

Yet the Infotrak poll shows that 60% of Kenyans are not keen on another constitutional review, wanting instead the constitution they voted for in a referendum in 2010 to be respected.

They would prefer their politicians to rule in accordance with the laws they have, agreeing with Russian writer Leo Tolstoy who once said: "Writing laws is easy, but governing is difficult."

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external