Coronavirus in South Africa: Scientists explore surprise theory for low death rate

- Published

Infection and death rates in many African countries have turned out to be much lower than initially feared. As the number of infections dips sharply in South Africa, experts there are exploring a startling hypothesis, as our Africa correspondent Andrew Harding reports from Johannesburg.

Crowded townships. Communal washing spaces. The impossibility of social distancing in communities where large families often share a single room...

For months health experts and politicians have been warning that living conditions in crowded urban communities in South Africa and beyond are likely to contribute to a rapid spread of the coronavirus.

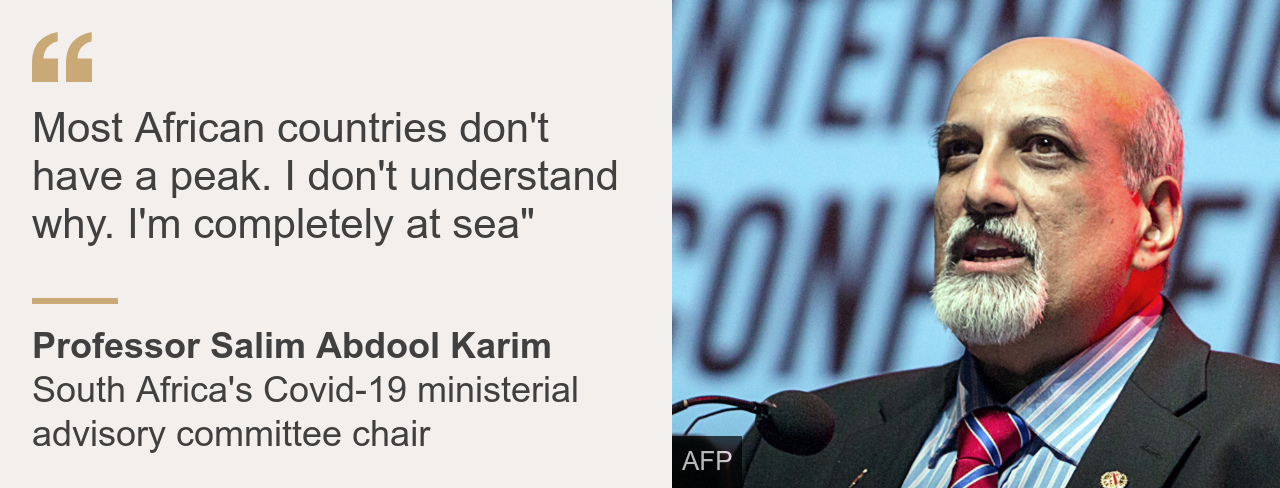

"Population density is such a key factor. If you don't have the ability to social distance, the virus spreads," said Professor Salim Karim, the head of South Africa's ministerial advisory team on Covid-19.

But some experts are now posing the question, what if the opposite is also true? What if those same crowded conditions also offer a possible solution to the mystery that has been unresolved for months? What if those conditions - they are asking - could prove to give people in South Africa, and in similar settings globally, some extra protection against Covid-19?

From early in the pandemic, South Africans were urged to wear masks when outside

"It seems possible that our struggles, our poor conditions might be working in favour of African countries and our populations," said Professor Shabir Madhi, South Africa's top virologist and an important figure in the hunt for a vaccine for Covid-19.

In the early stages of the pandemic, experts across Africa - echoed by many leaders - appeared to agree that the continent faced a severe threat from the virus.

"I thought we were heading towards a disaster, a complete meltdown," said Professor Shabir Madhi.

Even the most optimistic modelling and predictions showed, for example, that South Africa's hospitals - and the continent's most developed health system - would be quickly overwhelmed.

And yet, today South Africa is emerging from its first wave of infections with a Covid-19 death rate roughly seven times lower than Britain's.

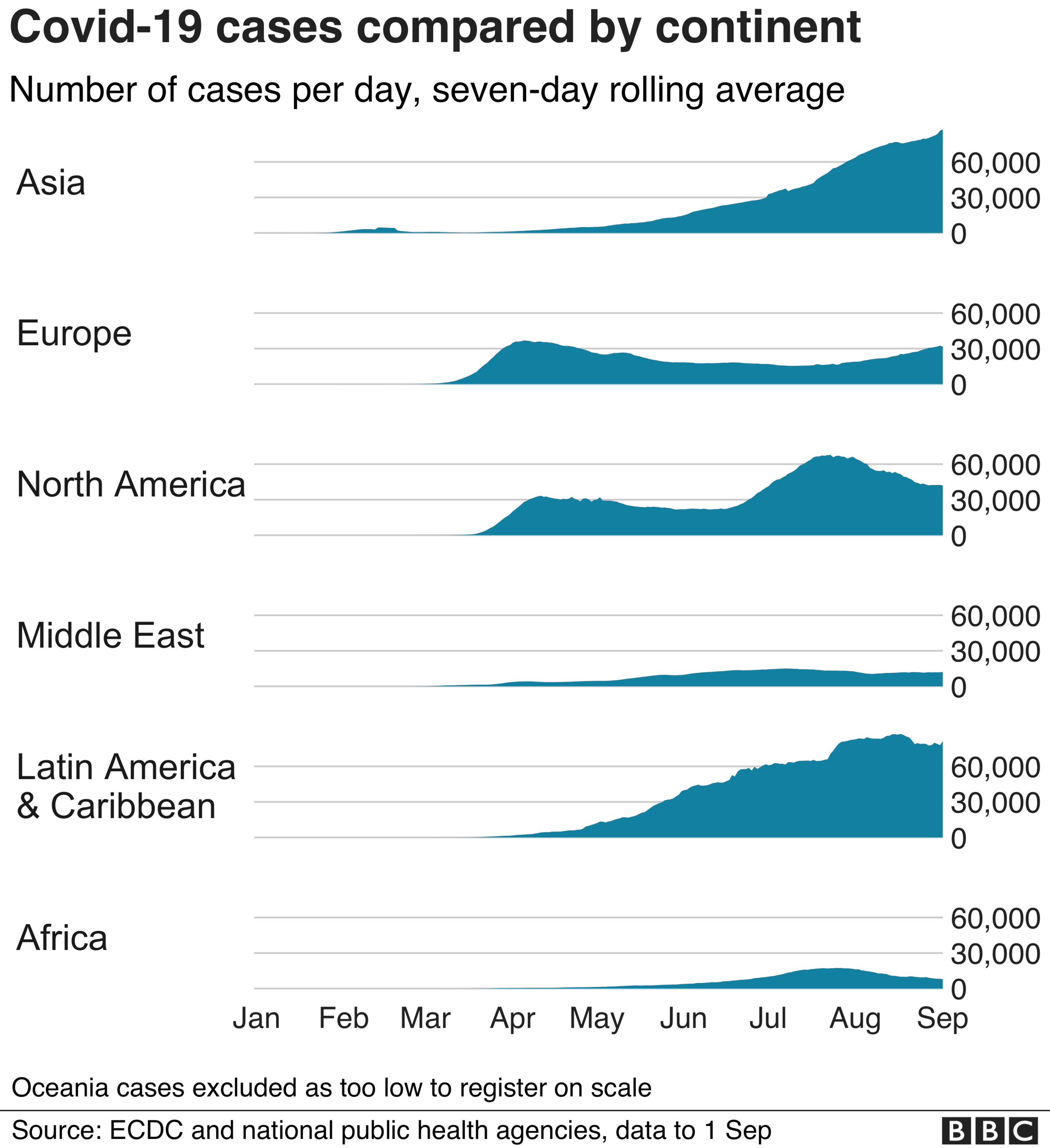

Scientists acknowledge that reliable data is not always easy to come by and all these figures are likely to change. But even if deaths have been under-reported here - perhaps by a factor of two - South Africa has still performed impressively well, as have many other parts of the continent, where many hospital beds remain empty, and where infection graphs have almost entirely avoided the pronounced peaks and sharp angles seen in so many other parts of the world.

"Most African countries don't have a peak. I don't understand why. I'm completely at sea," admitted Professor Salim Karim - widely seen as a leading voice on the pandemic response in South Africa and across the continent.

"This is an enigma. It's completely unbelievable," said Professor Shabir Madhi.

Coronavirus in South Africa: A day in the life of a contact tracer

For a while now, experts have cited a youthful population as the best explanation for Africa's relatively low infection rates. After all, the average age on the continent is roughly half that in Europe. Far fewer Africans live into their 80s, and so are less likely to succumb to the virus as a result.

"Age is the highest risk factor. Africa's young population protects it," said Tim Bromfield, a regional director of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

But as the pandemic drags on, and the statistical evidence builds up, analysts appear increasingly reluctant to give demographics all the credit for this continent's successes.

"Age is not such a big factor," said Professor Karim.

Early, and aggressive lockdowns here in South Africa and elsewhere on the continent have clearly played a crucial role. Clear messaging about masks and the provision of oxygen supplies have also been important.

You may also be interested in:

Other theories - about the impact of altitude or warmer temperatures - have generally been pushed aside. Some experts warn that the virus could still strike hard in the coming months.

"I'm not sure whether one day the epidemic is going to spread like crazy here," said Professor Karim.

Other coronaviruses

It is almost certain that many factors - particularly the quick lockdowns as well as youthful demographics - are likely to have contributed to South Africa's successes in tackling the virus thus far.

But in recent days, scientists at Vaccine and Infectious Disease Analytics unit, at Baragwanath hospital in Soweto, have been wondering if one missing factor might lie inside a glorified chest freezer in their laboratory, on the outskirts of Johannesburg.

The freezer - whose temperature is kept at minus 180 degrees centigrade, thanks to liquid nitrogen - contains metal cannisters storing five-year-old human blood samples. Or to be more specific, extracts from blood cells - known as PBMCs - acquired during an earlier influenza vaccine trial in Soweto.

![Quote card. Professor Shabir Madhi: "The protection might be much more intense in highly populated areas, in African settings. It might explain why the majority [on the continent] have asymptomatic or mild infections"](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/1280/cpsprodpb/4DDB/production/_114213991_582e7b78-fee5-45f6-b228-e649c598eff5.png)

The idea is that, by studying the PBMCs, the scientists might find evidence that people had been widely infected by other coronaviruses - those, for instance, responsible for many common colds - and that, as a result, they might enjoy some degree of immunity to Covid-19.

"It's a hypothesis. Some level of pre-existing cross-protective immunity… might explain why the epidemic didn't unfold (the way it did in other parts of the world)," said Professor Madhi, explaining that data from scientists in the United States appeared to support the hypothesis of some pre-existing immunity.

Colds and flu are, of course, commonplace around the world. But the South African scientists wondered whether, because those viruses spread more effectively in over-crowded neighbourhoods where it is harder for people to self-isolate, there might be an extra degree of immunity towards Covid-19.

"The protection might be much more intense in highly populated areas, in African settings. It might explain why the majority (on the continent) have asymptomatic or mild infections," Professor Madhi said.

"I can't think of anything else that would explain the numbers of completely asymptomatic people we're seeing. The numbers are completely unbelievable,"he said, expressing cautious hope that some of the challenges that have so often held back poorer communities might now work in their favour.

Sceptics - and there are plenty with any hypothesis like this - might point to countries like Brazil, with its crowded favelas, and its high infection rate.

Scientists are investigating the high numbers of asymptomatic infections in Africa

Unfortunately, as the scientists began preparing to test the PBMC samples in their laboratory, they spotted a problem. A quality-control test revealed that the icy temperature inside the cryo-containers had fluctuated over time - too much for the rigorous standards required for such an important, and delicate experiment.

"We're very disappointed. We were all ready but unfortunately this thing happened," said Doctor Gaurav Kwatra, who was leading the experiment.

The team is now busy hunting for new samples to test, but that may take months. In the meantime, South African scientists continue to hunt for new explanations for their nation's relative success in tackling the virus.

Update: The headline and article have been amended to better reflect what the scientists said. It was not our intention to cause offence.

GLOBAL SPREAD: Tracking the pandemic

How not to wear a face mask

- Published8 August 2020

- Published3 July 2020

- Published9 June 2020

- Published9 July 2024