‘Red, red wine': The meaning of African election symbols

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, media and communication trainer Joseph Warungu looks at why colours and symbols are so important in the pursuit of power in Africa as the continent gears up for an election season.

Remember red red wine? No, not the stuff in a bottle that allows you to unbottle your feelings.

I'm talking about Red Red Wine… one of the biggest cover hits by the British reggae group UB40. It reached the number one spot in the UK and the US in 1983.

Thirty-seven years later, Red Red Wine must have a lot of resonance for Ugandan pop star-turned politician Bobi Wine.

The MP, whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi and who is rarely spotted without his signature red beret, wants to run for president in the forthcoming elections.

But Bobi Wine is now seeing red after the electoral commission banned his National Unity Platform party from officially using the colour in the elections, saying another party had claimed it.

The easier the symbol, the better it is for parties to reach out to their electorate"

The power of colour and symbols in electoral campaigning cannot be underestimated in African countries.

"The easier the symbol, the better it is for parties to reach out to their electorate. Some of them think that it is good to have a symbol that people associate with hope and life at the end of the day," says Dr Isaac Owusu-Mensah, a senior lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of Ghana.

He uses the two main parties vying for power in Ghana's December election as an example.

"The opposition NDC party has an umbrella, and the interpretation is that you can be under the shade of the umbrella, especially in difficult times," says Dr Owusu-Mensah.

"The governing NPP on the other hand has the elephant, which is big. They can bulldoze whatever problem you have on your way. When you are in trouble, just go under the elephant and you are good."

'Red is for life'

Dr Mshai Mwangola, a performance scholar in Kenya, says in the West colours seem to have less symbolic meaning.

For example red is associated with the left-leaning Labour Party in the UK but with the conservative Republican Party in the US - and British Conservatives share blue with the US Democrats, who are liberals.

"Here in Africa, people know that those colours are full of meaning… we are very sophisticated in reading political discourse, in a multi-layered, multi-faceted manner," says Dr Mwangola.

These meanings are also read in the national flags of many African countries where there was a freedom struggle and people died, such as Kenya.

"Red symbolises the blood that was lost; black usually symbolises the people of the country and green is tied to the environment or land that they fought for," she says.

This is a view shared by Dr Owusu-Mensah.

"Red is a very important colour for political parties here. The NPP have the red, blue and white. When you go to NDC, they also have red, white and green. Senior members of the parties will say that blood is red; it means that that there is life in the colour and the party therefore has life."

Symbols gain significance even where none is intended.

In assigning symbols to the two opposing sides in the 2005 constitutional referendum in Kenya, the electoral commission went out of its way to find basic benign ones that would not give either side undue advantage.

Africa's election diary

Guinea: 18 Oct

Seychelles: 22-24 Oct

Tanzania: 28 Oct

Ivory Coast: 31 Oct

Ghana: 7 Dec

Central African Republic: 27 Dec

Niger: 27 Dec

Uganda: 10 Jan - 8 Feb 2021

The commission chose two fruits that are commonly available - an orange and banana. But Kenyans still read meaning into them.

The campaign saw all manner of political wrestling, with hilarious claims about what a banana could do to an orange and vice versa.

Kenyans had fun with the fruit symbols chosen for "Yes" and "No" sides of the 2005 referendum

In the end the oranges won and the government-backed referendum was rejected. The bananas lost.

The political grouping that was victorious in that poll adopted orange as the name of their new political party.

Today the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), led by former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, is the main opposition party in Kenya.

'Witchcraft' symbols banned

But not all symbols are welcome in an election as we saw in the 2018 poll in Zimbabwe.

You may also be interested in:

The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (Zec) banned a whole host of things from candidates' logos, including some animals and weapons, external.

You could have a gun in your logo but not a cheetah, elephant or leopard.

In its wisdom, Zec perhaps knew that there are many elections in Africa that are won not by the ballot but through "juju" or witchcraft, otherwise known as rigging.

So cobras and owls - associated with sorcery in Zimbabwe - were on the banned list.

The watermelon is a juicy and delicious fruit. But in Kenya it has sinister political connotations: a politician without concrete principles - green and hard on the outside and red and mushy on the inside.

He or she is not to be trusted. So, you won't find a campaign poster with the watermelon symbol.

Dr Owusu-Mensah argues that symbols are so powerful, they often replace the candidates' actual identity.

When growing up in a village in central Kenya, I always thought our long serving MP's name was 'Tawa' meaning lamp. That's because the lamp was his symbol in every election"

"I just came from a constituency in northern Ghana where we interviewed respondents about who they will be voting for in the coming elections. About 95% of them just used a symbol of either the elephant or the umbrella. They never mentioned the name of the party or candidate."

When growing up in a village in central Kenya, I always thought our long-serving MP's name was "Tawa" meaning lamp in my local language.

That's because the lamp was his symbol in every election. When his entourage swept through the village, the entire area would be filled with chants of "Tawa! Tawa!"

But I must admit, his lamp was rather faint: it did not illuminate our education and health challenges. It did not bring electricity to the area or improve the roads that were impassable in the rainy season.

Dr Mwangola agrees that while we are very good at getting the meaning of colours and symbols in Africa, we fail by not following through.

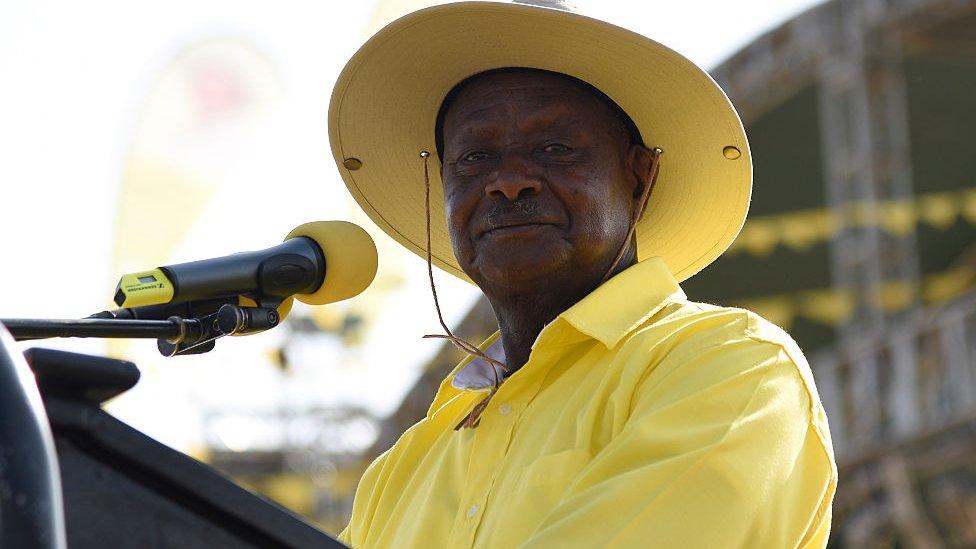

Uganda's President Museveni dressed in "joyous" yellow when he was last on the campaign trail

"We as voters, do not go back and hold the candidate accountable to the symbols. If someone had the symbol of a lamp or he was the axe, tractor or the lion, I no longer care. We don't even hold political parties to the symbols."

The Ugandan government fully understands the power of symbolism. A year ago, it designated the red beret as official military clothing that could land members of the public who wear them in jail. Though Bobi Wine seems determined to ignore this ruling too.

Dr Mwangola believes Bobi Wine may have chosen red as his colour to represent anger to counter the yellow of the governing NRM party, led by President Yoweri Museveni who is seeking a sixth term in office.

"Yellow is sunshine and joy. The other guys are saying: 'No, we're angry!'… it's been countered by the red of passion and commitment," she says.

"Yellow is about prosperity, but the red is saying: 'Prosperity for who?'"

If Ugandan voters do indeed see red come January, Bobi Wine may be sipping red wine from State House yet.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external