Ethiopia's Tigray crisis: How the conflict could destabilise its neighbours

- Published

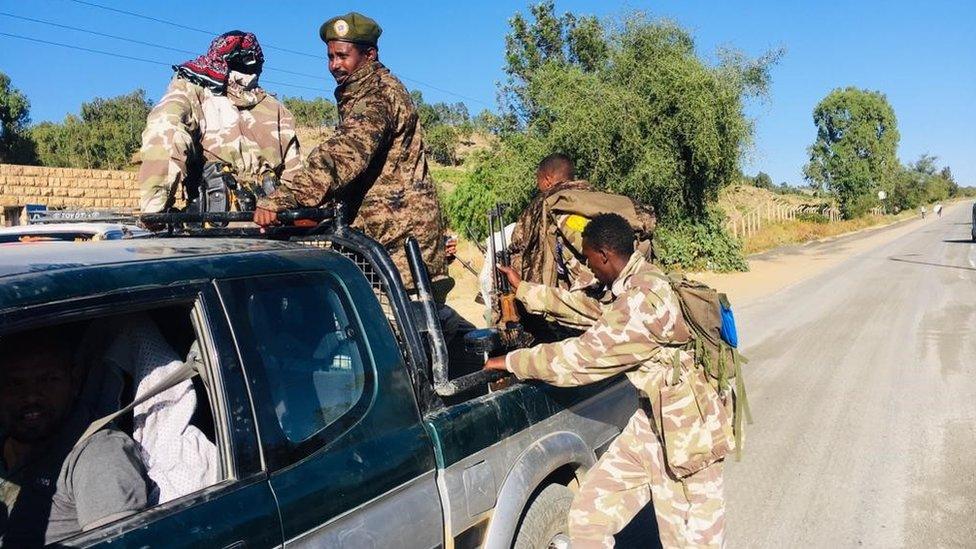

Militiamen from Amhara state, neighbouring Tigray, are fighting alongside the federal army

The fighting in Ethiopia's northern Tigray state may not only have drastic implications for the future of the country but could also seriously affect its neighbours.

Seeking to calm tensions a day after fighting started, UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that "the stability of Ethiopia is important for the entire Horn of Africa region".

With a population of more than 110 million and one of the fastest growing economies on the continent, what happens in Ethiopia inevitably has a wider impact.

Despite this, the federal government has so far resisted calls for diplomatic intervention to end the hostilities with the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), which runs the state.

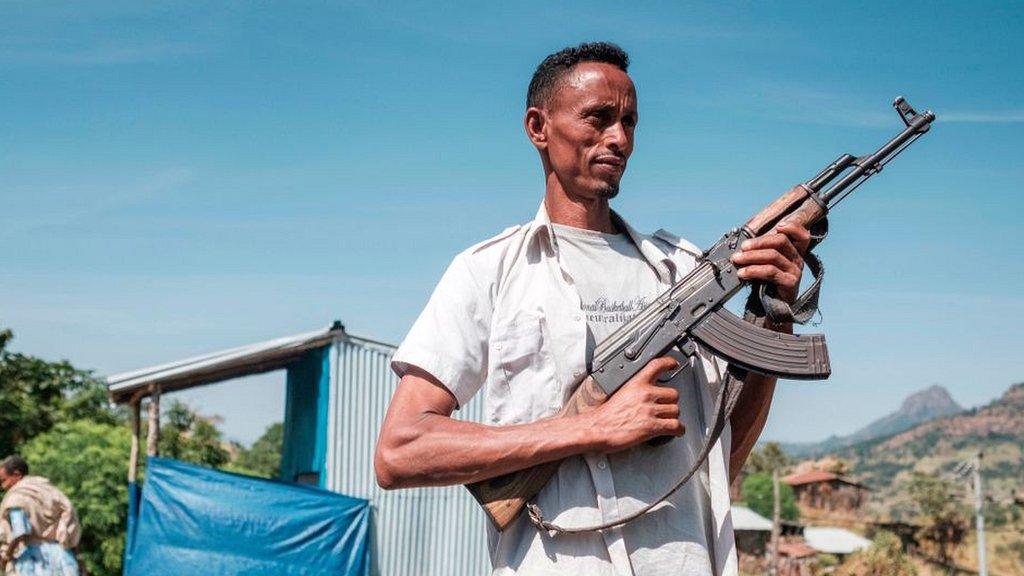

Thousands of refugees have already crossed into neighbouring Sudan

Instead it has launched a charm offensive aiming to persuade the world that this is an internal matter. The government has described the conflict as a "law-enforcement operation" against a "clique" intent on destroying Ethiopia's constitutional order.

This fighting may have been the result of long-standing tensions between the TPLF and the federal authorities, but the thousands of refugees crossing into Sudan indicates how this has spread beyond Ethiopia's borders, whether the government likes it or not.

'The impact is huge'

"The war is already regional," says Rashid Abdi, a Horn of Africa analyst.

"The Sudanese are involved and at some point it will involve other countries in the region, and also beyond, because it is a strategic region. The impact is huge."

He also believes that the conflict has drawn in Eritrea, which shares a long border with Tigray.

Eritrea has a history of poor relations with the TPLF, with its own scores to settle, and its President, Isaias Afwerki, is an ally of Ethiopian Prime Minster Abiy Ahmed.

There is no doubt that attacking across Tigray's northern border would open up a new flank in the fighting, but so far the Eritrean authorities have denied involvement in the crisis.

There is also a danger that the federal government's focus on Tigray could weaken its involvement in backing the government in Somalia against al-Shabab militants.

Ethiopia has already withdrawn about 600 soldiers from Somalia's western border, though they were not tied to the African Union's mission in Somalia (Amisom), which Ethiopia also supports.

"If the situation deteriorates further and Mr Abiy is forced to pull out of Amisom, that would be catastrophic... it will create an opportunity for al-Shabab to regrow and regroup again," says regional analyst Mr Abdi.

The International Crisis Group agrees, saying that unless the conflict is urgently stopped, it "will be devastating not just for the country but for the entire Horn of Africa".

'End of Ethiopia as a nation-state'

Regardless of the current involvement of Ethiopia's neighbours, some argue that the conflict could weaken the Ethiopian state, which could have damaging regional consequences in itself, with other groups in the multi-ethnic country emboldened to take on the central government.

Mr Abdi told the BBC that "what you will see essentially is the regions drifting away from the centre and the centre becoming weaker, unable to assert itself".

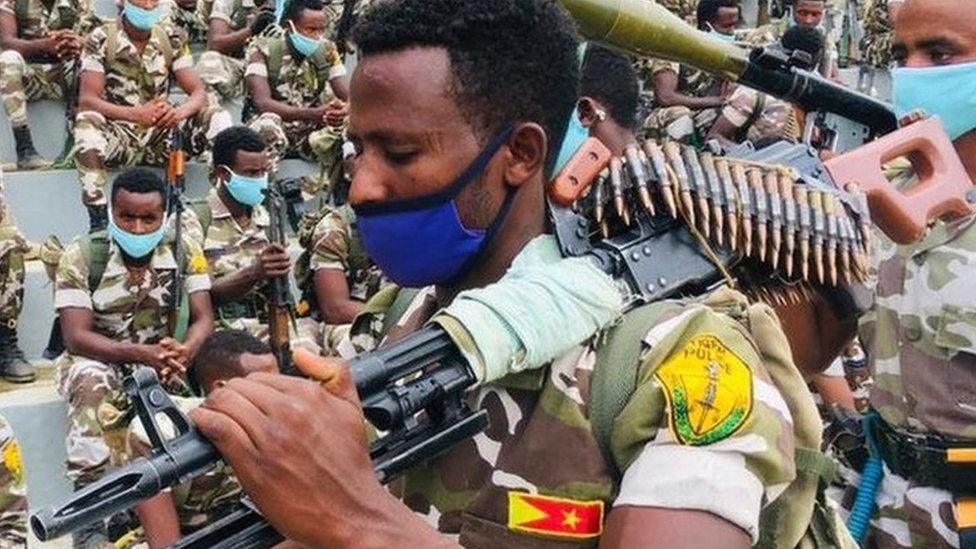

Tigrayan forces have taken control of an army base

But the director of Nairobi-based think-tank the Horn Institute, Hassan Khannenje, understands that Prime Minister Abiy needed to bring Tigray back in line with the federal government to avoid a situation where others could follow its example.

"Mr Abiy sees this as setting a bad precedent for the other regions... a unilateral movement towards a potential secession will mean the balkanisation of Ethiopia, which could mean the end of Ethiopia as a nation-state," he told the BBC.

"His endgame is to bring the state back into the fold and hopefully move into elections next year as a united country. Which is going to very hard to do in practice, but it is not impossible."

In the meantime, the crisis could lead to thousands being forced from their homes either directly because of conflict, or because of the fear of conflict.

More on the Tigray crisis:

Four things that explain the crisis in the Tigray region of Ethiopia.

Growing numbers have been crossing into Sudan and on Friday the UN's refugee agency said that the speed of new arrivals risked "overwhelming the current capacity to provide aid", the Reuters news agency quoted a spokesman as saying.

The Sudanese government has agreed to the establishment of a camp for 20,000 people 80km (50 miles) from the border and more sites are being identified, the UN says.

Added to this is the spectre of food shortages, with the region being one of the worst-affected by a desert locust infestation, with threats of new swarms arriving in the coming weeks, according to a recent UN humanitarian report, external.

Last thing the region needs

About 600,000 people in Tigray - about 10% of the population - already rely on food aid and across the country around seven million people face food shortages, the UN says.

If the fighting does continue, the numbers of people needing assistance would increase rapidly in a region already under pressure on other fronts.

The UN adds that the threat "of uncontrolled diseases and desert locust infestation" reaching other parts of Ethiopia and neighbouring countries "is high".

Ethiopia's size and strategic position in the region means that what happens in the country cannot necessarily be isolated, whether that is the fighting itself or the humanitarian fall-out.

The prime minister is confident that this will be a short conflict and insists that it is a purely Ethiopian issue, but if it is prolonged then it could have serious repercussions for many of its neighbours.

- Published13 November 2020

- Published11 November 2020

- Published10 December 2019

- Published29 June 2019