Viewpoint: Why Kenya's giant fig tree won over a president

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, media and communication trainer Joseph Warungu looks at the power trees seem to have over Kenyan politicians.

Governments are not always known to listen to their people.

If they did, the streets of Uganda's capital, Kampala, would not have been filled with so much violence recently as the strong arm of government rained down blows on its people to silence the voices demanding change amid their electoral season.

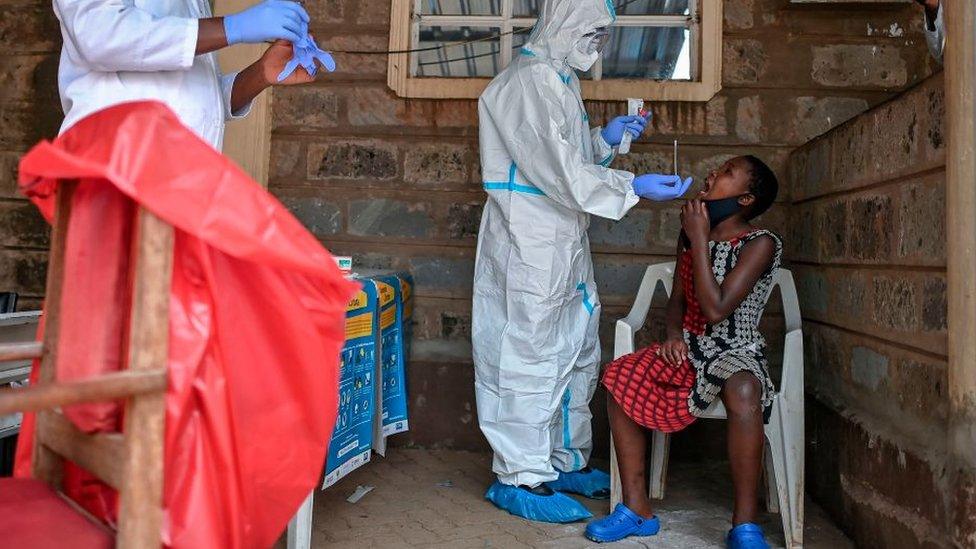

In Kenya, people have been pleading with government and politicians to help stop the spread of Covid-19, by abandoning their political rallies aimed at persuading people to endorse a possible constitutional referendum.

Coronavirus cases have spiked recently in Kenya

If the referendum does go ahead and is approved by the people, it will allow a major change to the constitution, that will restructure power and create more political offices, including a huge increase in the number of elected parliamentarians - all at the expense of the taxpayer.

Politicians in the governing party as well as the opposition, which also backs the referendum, refused to listen, with massive rallies in recent weeks attracting huge crowds, including many people who had abandoned their face masks.

This has been blamed for the worrying Covid-19 situation in Kenya where coronavirus infections have shot up with many more people dying now than in previous months.

So, it came as a big shock to Kenyans when one tree spoke and the government listened.

The Kikuyu do not allow a fig tree to be cut down - they believe such an act could spell disaster"

But it is no ordinary tree.

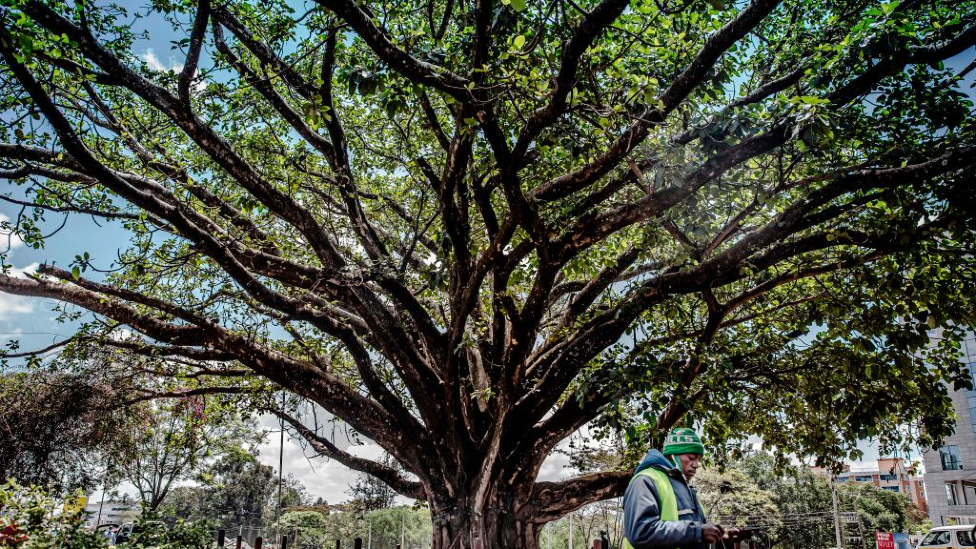

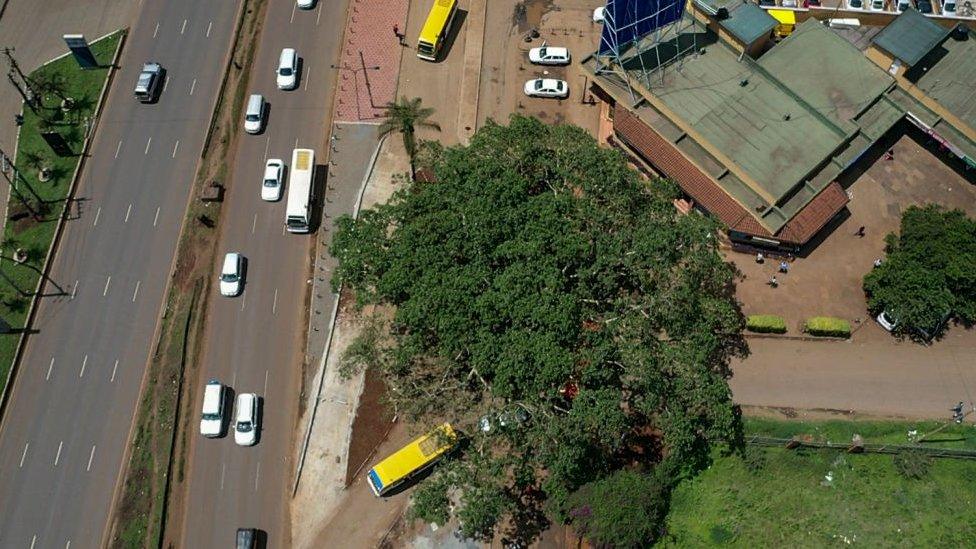

The majestic fig tree, which is 100 years old and towers over a section of Waiyaki Way in the west of Nairobi, had been sentenced to death to make way for an expressway that is under construction.

The 27km (16-mile) road will link the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport to the Westlands area of Nairobi, joining Waiyaki Way, the main road that leads to western Kenya and Uganda.

'Beacon of cultural heritage'

No-one quite knows why exactly the president changed the mind of government and issued a decree to spare the fig tree.

The plan was to chop down the 100-year-old tree to widen the road

He simply described it as a "beacon of Kenya's cultural and ecological heritage".

Indeed, the tree has huge cultural and religious significance for Bantu-speaking communities.

Some sections of the Luhya community in western Kenya, such as the Maragoli, revere the "mukumu" or fig tree. It was traditionally a courtroom under whose branches, cases would be heard and determined by elders. Fig trees are also used as landmarks in Maragoliland.

Signal to transfer power

For the Kikuyu people of central Kenya, the most populous ethnic group in the country, the fig tree known as "mugumo" has traditionally been a shrine, a place of worship and sacrifices.

The Kikuyu do not allow a fig tree to be cut down - they believe such an act could spell disaster.

When a fig tree withers or falls to the ground naturally, the Kikuyu see it as a bad omen or a signal to transfer power from one traditional age set or generation to the next. Each generation rules for about 30 years.

You may also be interested in:

A solution that's slowing desertification on the front lines of climate change

President Uhuru Kenyatta, who is himself Kikuyu, may have been the bearer of some bad news for Kenyans in his political life, but I'm not sure he fancied carrying the cultural and spiritual burden of a dead mugumo tree.

While environmentalists campaigned to stop the destruction of the tree, Kikuyu traditionalists watched with bated breath and stood with the tree and against the destruction of their culture.

This is not the first time that a stubborn government has been stopped in its tracks by nature as it attempted to erode the environment.

In the late 1980s the then ruling party - the Kenya African National Union - came up with a grand plan to build a massive skyscraper as its headquarters in the middle of Nairobi's famous Uhuru Park.

Protesters mounted a campaign to save the fig tree

At 60 storeys, the Times Media Complex with offices, shopping malls and parking for hundreds of cars, was going to be the tallest building in the East Africa region.

Environmentalists led by the late Nobel Peace Prize laureate Prof Wangari Maathai launched a campaign to fight the building and save the park.

In the end, Daniel arap Moi, who was then president, grudgingly listened to the voice of Uhuru Park and its trees.

Without fanfare, the skyscraper was scrapped and today many residents of Nairobi still have a serene green space for family outings and picnics.

'Chinese bewilderment'

The Waiyaki Way fig tree too can breathe easy as it has also been spared.

When I visited the site this week, the workmen had drawn plans for how the trenches they were digging would skirt around it.

Trenches are now being dug around the Waiyaki Way fig tree

One taxi driver told me: "After the president's decree, the Chinese [contractor] came, stared at the tree, stared at the tunnel that was meant to cut through the tree and walked away shaking his head."

The Chinese might have wondered what kind of powerful language the mugumo tree spoke to force engineering to stop, listen and detour.

The Kikuyu word for tree is "muti" and they use the same word for ballot.

The fig tree has won the vote to stay alive and keep the Chinese-funded expressway at bay.

Many Kenyans wish many more trees will stand up and vote "no" to selfish political moves that could endanger lives in a time of coronavirus - and their pockets if the referendum passes.

But will the government listen?

Let's wait for the trees to speak.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published4 July 2023