Is Africa overtaking the Middle East as the new jihadist battleground?

- Published

British soldiers have been training to join multinational troops in Mali

About 300 British troops have arrived in the troubled West African state of Mali at a time when the epicentre of the Islamic State group (IS) appears to have moved from the Middle East to Africa.

In a three-year mission named Operation Newcombe they are joining a force of around 15,000 UN multinational troops, spearheaded by the French, in efforts to help stabilise a part of the continent known as the Sahel.

Mali is one of several Sahel nations currently fighting jihadist insurgencies and the violence is getting worse.

According to the Global Terrorism Index published on 25 November, the "centre of gravity" for the Islamic State group IS has moved away from the Middle East to Africa and to some extent South Asia, with total deaths by IS in sub-Saharan Africa up by 67% over last year.

"The expansion of ISIS affiliates into sub-Saharan Africa led to a surge in terrorism in many countries in the region," reports the Global Terrorism Index.

"Seven of the 10 countries with the largest increase in terrorism were in sub-Saharan Africa: Burkina Faso, Mozambique, DRC, Mali, Niger, Cameroon and Ethiopia".

The report points out that in 2019 "sub-Saharan Africa recorded the largest number of ISIS-related terrorism deaths at 982, or 41 per cent of the total".

'Next stage in fight against terrorism'

Jihadists have long been active in Africa.

In modern times the late al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden made Sudan his base before moving back to Afghanistan in 1996.

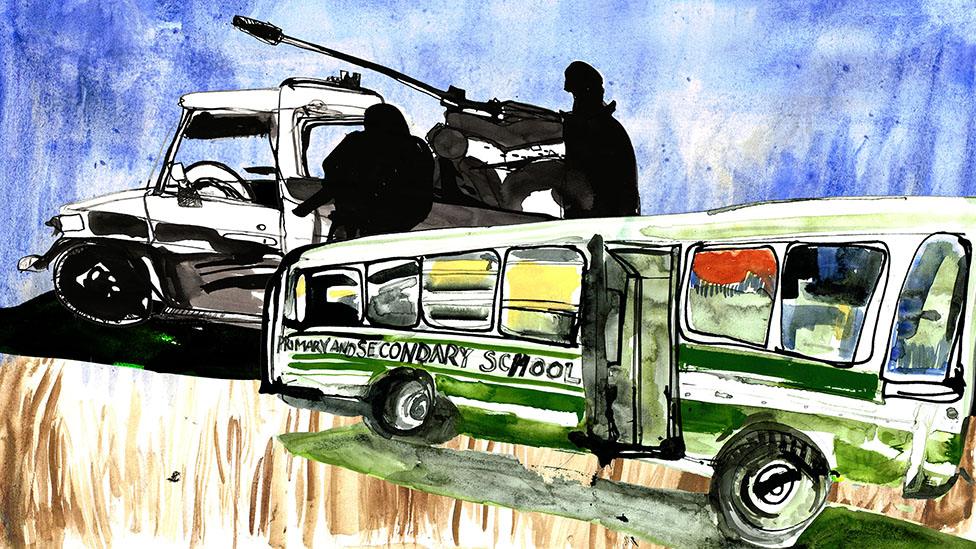

Nigeria's Boko Haram movement, infamous for kidnapping hundreds of schoolgirls at Chibok in 2014, carried out major attacks after declaring a jihad in 2010.

But today, as competition increase between rival jihadist groups, the threat of terrorism in the region is increasing.

The US State Department's coordinator for counter-terrorism, ambassador Nathan Sales, says both IS and al-Qaeda have shifted much of their operations away from their heartland in Syria and Iraq to their affiliates in West and East Africa, as well as Afghanistan.

"Africa", he says, "is a key front in the next stage in the fight against terrorism".

The archaeological site of the Tomb of Askia in Mali is protected by soldiers against a possible jihadist attack

But it is not just a case of governments versus insurgents, there is also a deadly rivalry taking place between supporters of al-Qaeda and IS. This rivalry is becoming so intense that French expert on jihad Olivier Guitta from GlobalStrat Risk Consultancy even predicts:

"Africa is going to be the battleground of jihad for the next 20 years and it's going to replace the Middle East".

Al-Qaeda and IS share a common loathing for secular, Western-supported rulers whom they call "apostates".

But they also have major differences in their approach.

IS has a predilection for extreme, graphic, violence - as demonstrated by its gruesome beheading videos.

While this certainly attracts sociopaths and convicted criminals to its ranks, it also tends to repel the vast majority of Muslims.

Al-Qaeda and its affiliates often seek to win over the loyalty of local populations who have no confidence in their governments or their police, exploiting regional and ethnic grievances.

Which countries are most at risk?

Mali and the Sahel

Several of the world's poorest nations border the Sahara desert.

This region is known as "the Sahel", an Arabic word literally meaning "the coast".

Mali, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mauritania make up the Sahel countries and all have suffered attacks from insurgents.

What is the Sahel G-5 force?

Parts of the region are afflicted variously with drought, poverty, unemployment, corruption and in some cases large tracts of ungoverned space.

"West Africa", says ambassador Sales, "is a perfect storm, with nation states that don't control their territories, commit abuses by their forces, and have porous borders".

The dominant jihadist group in this region is the al-Qaeda affiliate Jama'at Nusrat Al-Islam wa'l-Muslimin (JNIM).

The group is in direct competition with the IS affiliate Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and this year has seen a number of low-level battles between them.

Nigeria

Nigeria has suffered some of the worst jihadist attacks in the region, with the government struggling to control the north-east of the country where the Boko Haram movement evolved.

According to the Global Terrorism Index, Boko Haram has been responsible for over "37,500 combat-related deaths and over 19,000 deaths from terrorism since 2011, mainly in Nigeria" but also neighbouring countries.

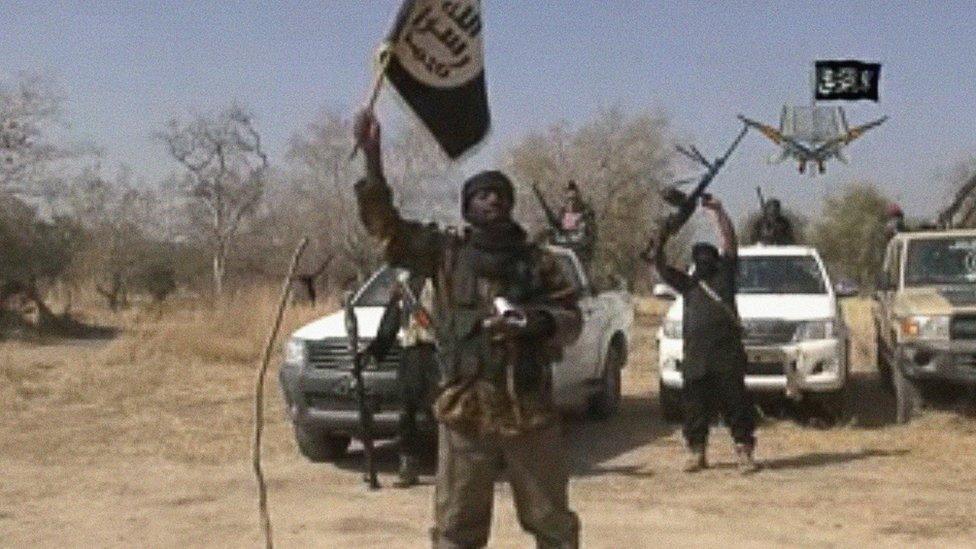

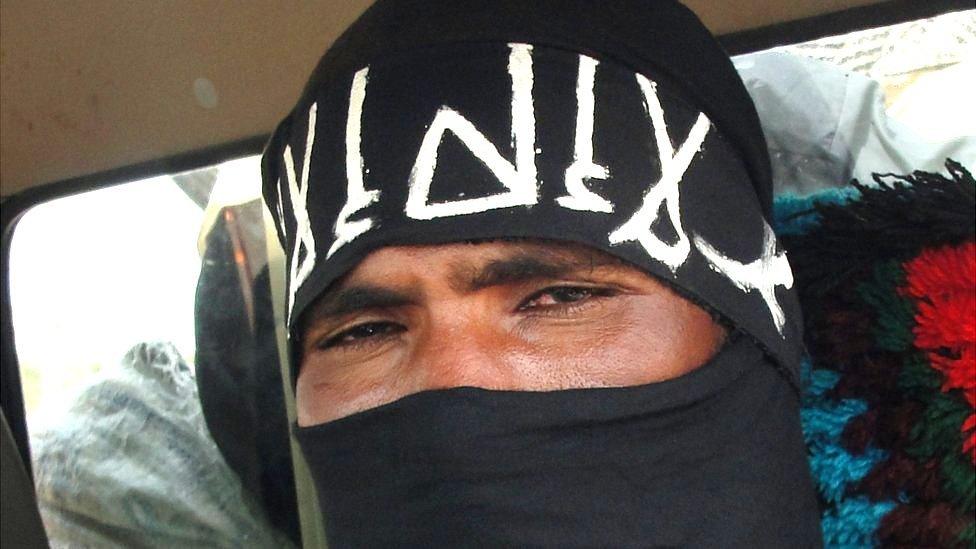

Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS in 2015

In 2015, one faction of Boko Haram pledged allegiance to IS, becoming "Islamic State West Africa Province" (Iswap), crossing borders with ease and capturing a multinational base on the shores of Lake Chad in 2018.

IS has since been heavily promoting this African affiliate.

Attacks are still being carried in Boko Haram's name. A video posted by the group on 1 December claimed responsibility for massacring dozens of farmers in Borno state who it claimed had collaborated with government forces.

Western nations have offered only limited military and intelligence assistance to Nigeria. Western diplomats say they are constrained by the corruption and poor human rights record of the Nigerian military.

These failings have been a major contributor towards mistrust of the government and towards recruitment for Boko Haram and other jihadist groups in the region.

"The corruption angle in Nigeria" says Olivier Guitta, "is ruining everything".

North Africa

Al-Qaeda's insurgency in North Africa started off in Algeria.

So it is no surprise that the newly appointed leader of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) is an Algerian.

The white-bearded 51-year-old Abu Obaida Al-Annabi replaces his predecessor, Abdelmalik Droukdel, who was killed by French troops in Mali in June.

In a microcosm of the wider al-Qaeda-IS rivalry, his appointment has been cheered by al-Qaeda's supporters while rival IS supporters have cast doubt on his jihadist credentials.

Tens of thousands of Tunisians travelled to Syria, pictured here in 2018, to join IS

Tunisia, the smallest country in the region, produced one of the highest numbers of volunteers - 15-20,000 - who travelled to Syria to join IS during its peak years of 2013-2018.

With high unemployment and a proximity to Libya, Tunisia continues to face an ongoing threat from terrorism.

Libya has been in a state of intermittent chaos ever since the Arab Spring revolt of 2011 and the overthrow of the despotic regime of Muammar Gaddafi.

The end of his regime not only released thousands of tonnes of weapons and explosives from government armouries, much of it making its way across the southern border into the Sahel countries, it also allowed IS jihadists to gain a foothold in the east of Libya.

Somalia

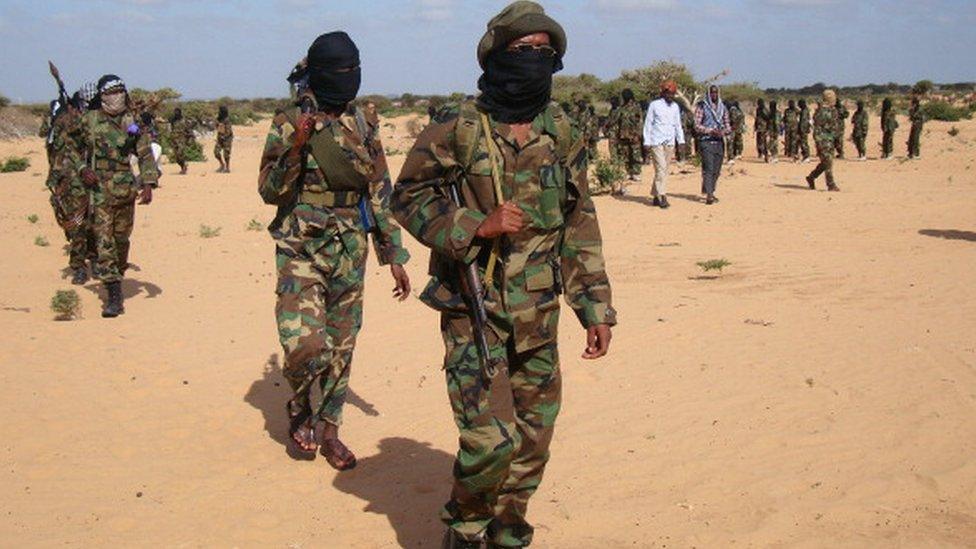

Somalia's al-Shabab group - Arabic for "the young men" - has been one of the most persistent and dangerous jihadist movements on the entire continent.

"Al-Shabab" says Nathan Sales, "sees itself as al-Qaeda's most successful group".

Al-Shabab has survived military efforts to stop its activities

It has survived concerted multinational military campaigns to eradicate it yet it has been able to strike across its borders in Kenya and Uganda as well as detonating massive bombs in the Somali capital, Mogadishu.

US Special Operations raids and drone strikes, launched from neighbouring Djibouti, frequently kill al-Shabab leaders and yet the group has been able to keep regenerating itself.

It has also succeeded in beating back a challenge from the local IS affiliate which is now largely confined to the north-east tip of the Horn of Africa.

Mozambique

The foothold gained by IS in the northern district of Cabo Delgado under the banner of "Islamic State Central Africa Province" (ISCAP), could well be an example of a full-blown insurgency arranged almost entirely over the internet.

Counter-terrorism officials believe that the jihadists operating in this gas-rich part of Mozambique have been recruited online with some input from across the border in Tanzania but largely without the physical presence of recruiters sent from the IS heartlands of Syria and Iraq.

WATCH: The Mozambique conflict explained

There are conflicting reports as to the veracity of some of the recent atrocities carried out in the name of IS in Cabo Delgado, such as the alleged massacre of around 50 villagers on a football field.

But IS does appear to be getting the upper hand against the government.

"IS" says Olivier Guitta, "is moving around within Mozambique unhampered by other forces".

Hostage ransoms

This is a hugely contentious issue.

In June 2013 all seven leaders at the G7 summit at Loch Erne signed up to an agreement not to pay ransoms to proscribed terrorist organisations.

Seven years on and the reality remains that European citizens tend to be eventually released for undisclosed amounts while British and American hostages are the most likely to get executed.

Several French citizens have been released from jihadist captivity in the Sahel, most recently in exchange for the release of a large number of dangerous jihadist prisoners in Mali.

Analysts have put the total amount paid to jihadist kidnappers in North and West Africa over the years at more than €100m ($120m; £90m).

This ransom money is then used by the jihadists to buy more weapons, more explosives, better vehicles, night vision goggles, communications equipment as well as funding their recruitment efforts and providing bribes to corrupt officials.

No quick fix

So, is Africa, as some are predicting, really set to overtake the Middle East as the primary theatre of violent jihad?

This will depend on many factors but chief amongst them is the quality of governance.

The long-term solution to the challenge of jihadist insurgencies is not just about better policing and stronger borders.

It comes back to the age-old challenge of creating the economic opportunities and political stability that eventually steer people away from a life of violence.

- Published5 May 2020

- Published20 November 2015

- Published22 December 2017

- Published11 May 2020

- Published23 November 2020