Africa's free-trade area: What difference will it make?

- Published

This factory in Kenya makes face masks but many African nations buy their face masks from China

Africa's free-trade area became reality on 1 January 2021, promising to make it easier to do business across the continent.

The idea, which has been talked about for years, is to create one of the world's biggest free-trade areas, opening up a market of more than 1.2 billion people, with a combined GDP of more than $3 trillion (£2 trillion). This would create business opportunities - and jobs - across Africa, while reducing the cost of some goods in the shops and markets.

The launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area follows years of negotiations and preparations, and more recently faced months of delays due to the global coronavirus pandemic.

What happened on 1 January?

From that date, the 41 countries that had submitted their plans to reduce tariffs, or taxes on imported goods, were able to trade goods under the new rules. Each state or regional trade bloc makes their own plans and that information is eventually hosted on the Africa Trade Observatory (ATO) website, external.

Under the trade deal, tariffs on 90% of goods will be phased out within 10 years and more for the remaining 10%. This is being done in stages and so could take up to 2035, according to the AfCFTA secretariat.

So has the price of goods in the shops changed?

No, not yet.

For the prices in the shops and markets to change, the taxes on imported goods must go down first. While many of the countries have officially reduced the taxes, and so some of the goods are eligible for the lower tariffs, this is yet to take effect.

The price of these South Africa oranges might soon fall in Kenya

This is because countries are first required to gazette (or publish in an official record) the specific changes on tariffs and this information is published on the ATO website. Because this process is not yet complete, the duty or taxes being paid has largely not changed. Besides, not all countries that have offered to reduce the import taxes have finalised their customs processes, such as the procedures for presentation, identification and clearance of goods.

"In most cases," David Luke, a trade policy expert at the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa says, "the duty will be refunded [later] since the process, including gazetting is in progress".

But once the reduction in taxes does take effect, which depends on when individual countries complete their processes, the prices of goods should fall.

For example, oranges imported from South Africa for sale in a supermarket in Kenya currently attract a 25% tariff, according to the African Trade Observatory. So if Kenya removes this tax, and all the required processes are ready, the price of those oranges should significantly fall.

Andrew Mold, the head of regional integration and the AfCFTA cluster at Uneca, reckons the price reduction will be quite modest for goods such as food and building materials but there will be more pressure to reduce service sector prices.

"With greater competition, we should see prices come down for services like telecoms, business services and finance," he says.

What difference will it make to traders?

It could potentially make a big difference to people trying to export goods from one African country to another.

Mabel Simpson is a creative fashion entrepreneur in Accra, Ghana, who makes items with African prints such as handmade laptop bags, hand bags and pillows. Most of the raw materials she uses are imported and she says that taxes on them make the final products too expensive to sell elsewhere on the continent.

If I need to ship an item to the US... it's going to be $25 but if I need to ship the same item to Uganda, it's going to be $60"

Her biggest export markets are currently the United States and the UK, as factors such as import taxes and other costs make goods too expensive to sell elsewhere in Africa.

"If I need to ship an item to the US, if I ship an item that weighs one kilo, it's going to be $25 but if I need to ship the same item to Uganda, it's going to be $60. So, which is cheaper? The USA."

If she was able to sell her goods profitably in Uganda, and other African countries, she says she would, potentially creating more jobs for her employees in Ghana, and those selling her products elsewhere.

She also says an African free trade area could make her products cheaper because she currently pays taxes on those goods she imports.

"This [AfCFTA] means we are going to be able to produce in numbers and more people are going to be able to afford our products and we are going to be able to be more competitive in Africa," she says.

What about bigger firms?

With a large and seamless market for goods, the free-trade area is expected to attract more domestic and foreign investment, fostering industrial growth in the continent.

This is one of the objectives of AfCFTA, which will be the world's largest free trade area by number of countries once it is fully operational.

Could a free-trade deal be a new dawn for Africa?

However, some smaller companies may be worried they will not be able to compete with continental giants and multinationals. The AfCFTA is negotiating a protocol on competition policy this year which aims to create a level playing field for all firms.

The UN and World Trade Organization's joint agency, the International Trade Centre, says that the free trade area could also make it easier for small companies to expand into neighbouring countries., external

Small firms could find niche markets but can also specialise as part of the supply chain of larger firms.

Some obstacles still remain, including poor physical infrastructure such as road and railway networks, customs systems, security issues and communication barriers that may yet still pose a problem for the free movement of goods within the continent.

Why is the African Union so keen on a free-trade area?

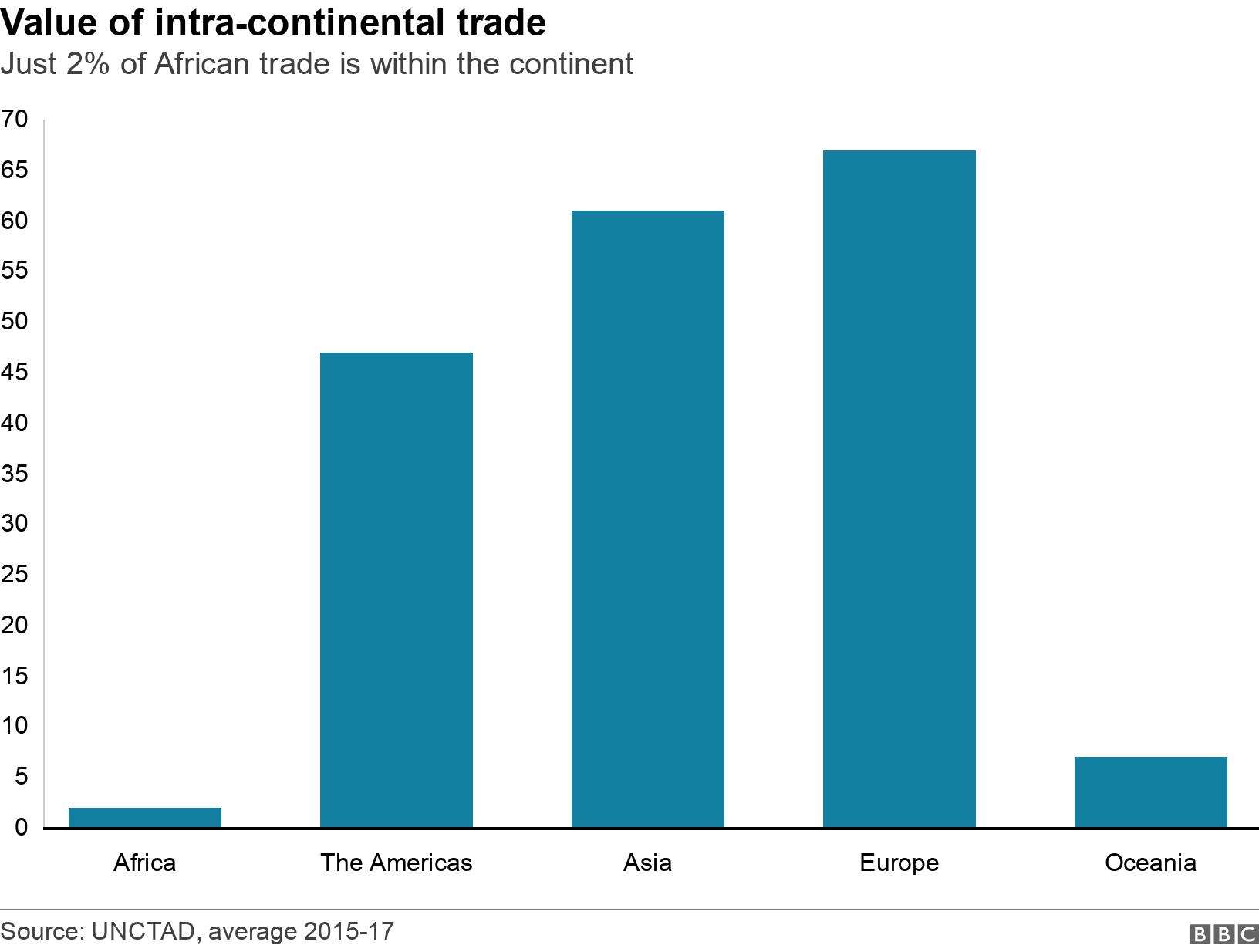

Basically because trade between African countries is relatively low.

Poor infrastructure and customs delays are other reasons why intra-African trade is so low

For example, Kenya is a major flower exporter but Nigeria imports flowers from the Netherlands. Similarly, palm oil in Kenya is likely to come from Malaysia, rather than Nigeria.

The idea behind the free-trade area is to see Kenyan flowers on the streets of Lagos and Nigerian palm oil for sale in Nairobi.

Across the continent, just 2% of trade was with other African countries in the period 2015-17, compared to 47% in The Americas, 61% in Asia, 67% in Europe and 7% in Oceania, according to UN trade agency, Unctad.

Many countries still do more trade with their former colonial power than they do with their neighbours.

The theory is that if African countries did more business with each other, they would all benefit, creating more jobs and so raising living standards across the continent.

The trade area also seeks to resolve the challenges of multiple and often overlapping membership of regional trade blocs, such as the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa), Ecowas in West Africa, Sadc in the south and the East African Community.

So what happens next?

This is just the start of a journey, which could last up to 2035.

The deal, signed by 54 of the African Union's (AU) 55 member states, and ratified by 34 so far, commits countries to remove tariffs on 90% of products within a five-year period.

You may also be interested in:

Trade under AfCFTA cannot yet commence on the remaining 10% of goods, whose negotiations are yet to be finalised, according to Mr Mold of the Uneca.

He notes that the implementation of the free-trade area is a process rather than an event that will take quite some time to fully implement.

Negotiations continue this year, he says, including on the services sector, before the negotiators move to the Phase II issues - such as rights of investors, competition policy, and intellectual property.

"All this is part and parcel of a gradual harmonisation of African trade and investment policies to facilitate much greater levels of intra-African trade and investment," he told the BBC.

Why was it delayed?

The global coronavirus pandemic pushed back the implementation of the trade deal that was meant to start in July 2020.

Negotiations have taken years, since 2012 when the African Union launched the plan for establishing a free-trade area.

Africa's leaders signed up to the African free trade deal in 2018

The closure of economies around the world due to the pandemic, however, is seen as increasing the need for intra-regional trade and integrating African economies which have been heavily dependent on imports from China, Europe, US and elsewhere.

"Covid-19 has demonstrated that Africa is overly reliant on the export of primary commodities, overly reliant on global supply chains," said Wamkele Mene, secretary-general of the AfCFTA secretariat during the launch of the free-trade area.

"When the global supply chains are disrupted, we know that Africa suffers."

Are all countries on board?

In 2018, 44 countries signed the deal while 10 including Africa's biggest economy Nigeria, were initially reluctant to sign, before later agreeing to join up.

Of the 55 countries in the continent, only Eritrea remains to be part of the trading bloc.

A total of 34 countries have ratified the deal and 41 countries and customs unions have submitted their offer to reduce tariffs. That means that nearly all favour the agreement, though countries have made varying levels of commitment.