Coronavirus in Algeria: 'No-one could travel to say goodbye to grandpa'

- Published

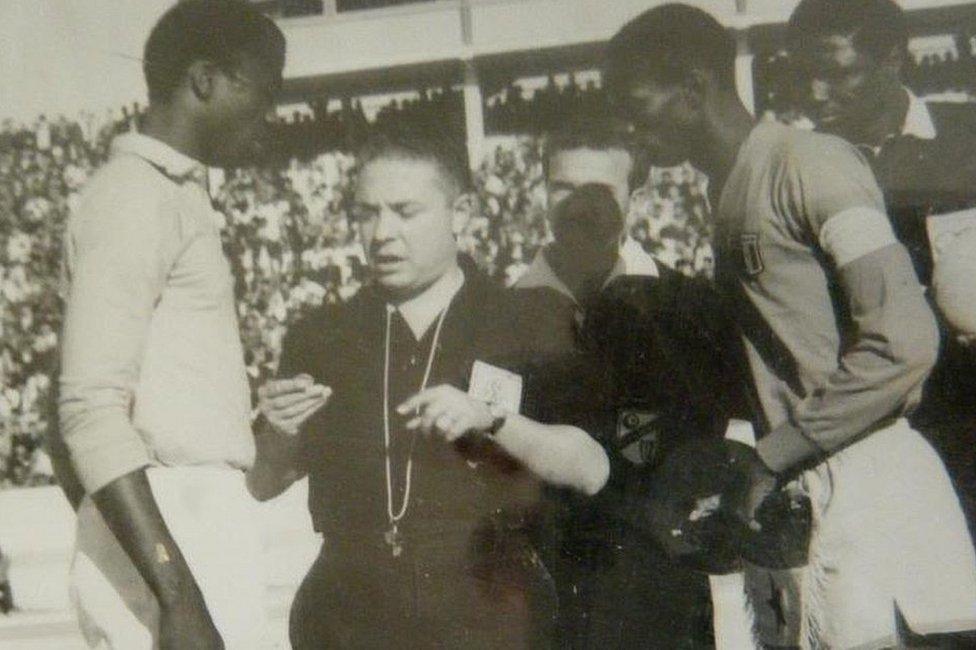

Maher Mezahi's grandfather, seen here at the Africa Cup of Nations in 1965, was a prominent Algerian referee in the 1960s

In our series of letters from African journalists, Algerian-Canadian journalist Maher Mezahi reflects on how coronavirus has increased the separation between families around the world.

Funerals are incongruous events - an act of both separation from one we loved and solidarity with those left behind.

Unloading the burden of loss is only seemingly possible by sharing it with others.

There are more than six million Algerians dispersed across the Mediterranean region and in pockets across North America. For those of us from the diaspora, it is not uncommon to miss the funeral services of our loved ones.

In Algeria, the custom is to promptly bury the deceased.

Burial rites are usually completed by the next day's Asr (or mid-afternoon) prayer, so they are virtually impossible to attend from other continents.

I slowly grew into the role of logistics officer, especially during family tragedies. It is a duty I take pride in, despite the petty procedural difficulties"

When my maternal grandmother passed away, for example, my mother flew in from Canada, but arrived two days after her mother was laid to rest in the family cemetery.

Although she could not properly mourn, my mother stressed the importance of being able to help host the overwhelming waves of guests that rolled in for couscous and coffee.

After leaving Canada five years ago and moving to Algeria to pursue a career in football journalism, I slowly grew into the role of logistics officer, especially during family tragedies. It is a duty I take pride in, despite the petty procedural difficulties.

On 17 March last year, when Covid-19 cases began sky-rocketing in Algeria, the government decided to close land, sea and air borders.

Domestic flights have resumed in Algeria but people can still not fly in from abroad

Many countries temporarily employed similar methods, but Algeria remains one of a handful of African nations that is yet to re-open commercial travel to its own citizens.

I remember hoping, at the time, that neither of my two elderly grandparents would contract the virus.

My paternal grandmother was 85 years of age and my paternal grandfather was 92. They both suffered from hypertension and my grandfather was diabetic.

Growing up in Canada, I had always shared an awkward relationship with my grandfather. He was well-dressed, sophisticated and enjoyed listening to the traditional Andalusian malouf music of Mohamed Tahar Fergani.

Our one area of common interest was football.

Mohamed Mezahi (behind the men holding the wreath) officiated at a 1956 North Africa cup match

He was a pioneer in the game — one of Algeria's first international referees.

He officiated some of Africa's first World Cup qualifying matches, the third-fourth-place match of the 1965 Africa Cup of Nations, as well as some of the biggest domestic fixtures in early Algerian footballing history.

So in the summer months when he would fly to Canada, or we would visit Algeria, both of us could sit in front of the television for hours and muse over dribbles, goals and assists.

'Could be bad'

In mid-August, I received a WhatsApp message from my mother, informing me that both of my grandparents were sick and that both were exhibiting Covid-19 symptoms.

"It could be bad," she wrote.

After checking in on them, I began to mentally prepare myself to act as a liaison between Canada and eastern Algeria, where my family is from. But it slowly dawned on me that, this time, my services would not be needed.

My grandfather, Mohamed Mezahi, passed away on Friday, 20 August. The following day, his PCR test came back Covid-positive.

I called my father to tell him I was sorry. He seemed lucid when responding: "I am going to take time off work and book a flight, can you drive me to Constantine?"

I agreed, but insisted he made sure travel was possible. He booked a flight with a European airline online, only for it to be cancelled the very same evening. He was offered a voucher instead.

Mohamed Mezahi was also an official at the 1966 Algerian Cup final

My father immediately tried booking for three days later. Again, on the eve of the flight, the airline informed him that his flight was cancelled.

His final attempt was for three weeks later, but I could tell that this time it was an empty gesture.

My grandfather was already buried in a downtown Constantine cemetery adjacent to my great-grandmother and great-uncle.

Sure enough, the final flight reservation was cancelled and a voucher offered instead.

"It's tough," I told him, "but all Algerians abroad are going through exactly the same thing."

"I hope the decision-makers have a clear conscience," he replied.

My grandmother, thankfully, recovered.

As of now, approximately 3,000 Algerians in Algeria have died from coronavirus, according to official statistics.

That is at least 3,000 funeral services where Algerians in the diaspora have not been able to unload the burden of loss by sharing it with loved ones.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

Related topics

- Published23 May 2020

- Published9 September 2024