Uganda's Yoweri Museveni overcomes Bobi Wine challenge - for now

- Published

Supporters of President Yoweri Museveni celebrated after the results were announced

The keenly contested Ugandan election that saw the country's long-standing leader defeat a former pop star was not without drama but has it heralded any change? The BBC's Patience Atuhaire reports from the capital, Kampala.

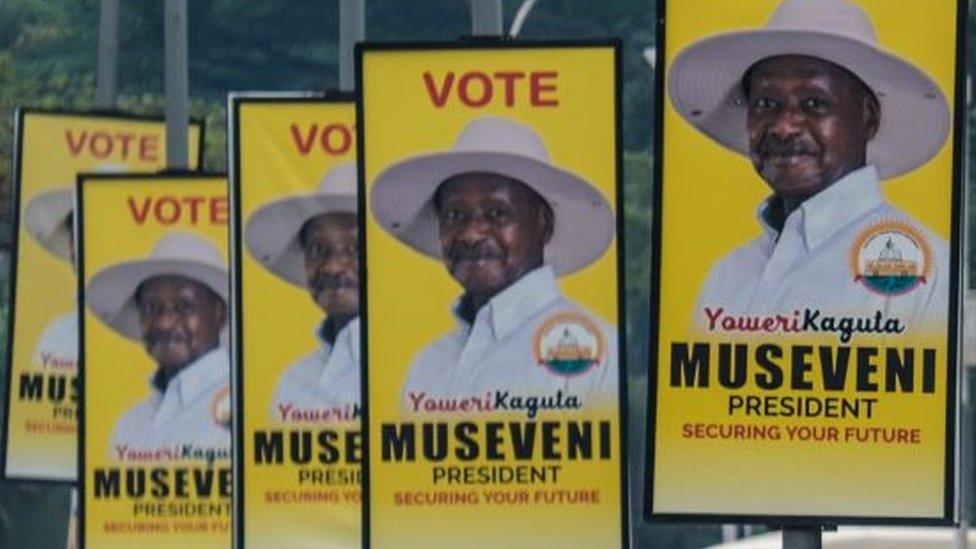

It was billed by some as an election like no other - a 38-year-old musician raised in a Kampala slum was challenging a man who first became president 35 years ago.

When Robert Kyagulanyi, better known by his stage name Bobi Wine, first launched his presidential bid, some in President Yoweri Museveni's ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) dismissed the threat.

They said he was only popular in the capital, but then he kept drawing crowds even in far-flung corners of the country. Then, as a government minister commented, it was claimed that the excitement around him was simply because he was a celebrity.

But it felt like more than that.

Tech savvy and accessible, Bobi Wine used social media to call on young Ugandans - the majority of the population - to work with him towards "a new Uganda". And they lapped it up.

Or so it seemed.

Social media is not votes

The authorities certainly appeared rattled. As the campaigning reached a crescendo, the tear gas, live bullets and arrests meted out to Bobi Wine and his supporters made it clear that the powers that be were leaving nothing to chance.

The NRM relied on incumbency and the full force of the state.

Bobi Wine (L) said he would not be intimidated by the force that his campaign met

Bobi Wine the performer, not Robert Kyagulanyi the politician, was the person on the campaign trail.

He worked the crowds - who gathered despite coronavirus concerns - into a frenzy with the "people power, our power" chant, complete with the arm-waving.

But what he wanted to do with that power was rarely fleshed out at the rallies. Even on the few occasions when the security forces took a break from harassing him, he hardly ever spoke about the issues in his manifesto.

In fact, covering this election was reduced to reporting the violence the opposition were subjected to, rather than the agenda the candidates were presenting to the electorate.

But the "people power" fire that Bobi Wine had lit among Ugandans seemed to burn all the way to the ballot box and then fizzle out.

Official figures, which the opposition alleged had been tampered with, would later show that the large rallies and social media popularity did not necessarily translate into a majority of votes.

Security forces have been stationed near Bobi Wine's home in Kampala

Bobi Wine got a respectable 35%, but this was nearly the same percentage won by the top losing candidate, Kizza Besigye, in 2016. And then, like Dr Besigye, Bobi Wine was confined to his home by security forces.

The aftermath of the election had a familiar feel to it.

Before this, the morning of the vote - when opposition optimists still dreamed of another future - was misty and chilly, quite uncharacteristic for a Kampala January.

'What's the hold up?'

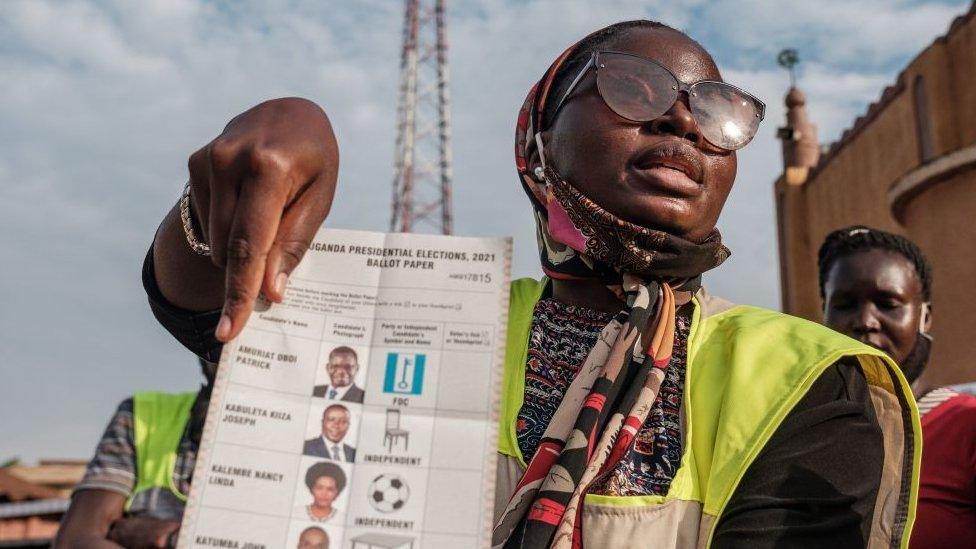

I arrived at a polling area in Nsambya, at the southern end of the city by 07:30, to find huddled groups of voters talking in muted tones.

The large sports field comprised five polling stations. The voting materials had arrived but the casting of ballots was yet to start.

As the queues grew longer, tempers rose with the warming temperatures. A young man shouted out what everyone must have been thinking: "We arrived here at 6am! What is holding us up?"

People queued to vote at polling stations in the capital, Kampala

Several others grumbled, some hurling insults at the polling officials. Either his outspokenness paid off, or the officials just wanted to get rid of him. When voting finally begun, two hours late, he was moved to the front of the line.

I crossed the city to another large polling area in Nansana, on the northern side, where voting was delayed until 10:00. With queues as long as the eye could see, I could read the agitation on people's faces.

"I arrived here and was told this is not my rightful polling station. When I went the other side, I was sent back here. I'm waiting. My friend had a voter location slip, but her name is not in the register. She got discouraged and left," said Fatuma Namuleme.

I recalled similar queues here in 2016, rivulets of sweat running down the faces of voters standing in the mid-morning sun, waiting for materials to arrive. I remembered heavily armed soldiers disembarking from lorries to take charge of an increasingly tense situation.

On that day, the voting process in Kampala was so marred by the late delivery of materials that there were protests in some areas and voting had to be pushed to the next day.

But this time, there were only a couple of baton-wielding policemen ensuring the lines were orderly.

With an internet blackout and limited access to information from other parts of the capital and the countryside, voting day felt like an anti-climax.

Bobi Wine's party says there were irregularities in the results

As updates from the Electoral Commission streamed in, it became quite clear from early on where the poll result was headed - five more years for Mr Museveni.

Despite the long queues witnessed in Kampala, only 57% of over 18 million registered voters cast their ballots, 10 percentage points lower than the last election.

The president's winning percentage has also been steadily declining in the last three elections; from 68% in 2011, to 60.6% in 2016 and 58.6% this year.

And the opposition has kept a hold on Kampala and much of the central region.

Ministers lose their seats

Bobi Wine's newly formed National Unity Platform (NUP) party won most of the parliamentary seats in central region and will have a total of 56 MPs out of more than 500, making it the largest opposition party in parliament.

The NUP has become a home for younger, energetic politicians looking for fresh alliances who could shake things up.

The 2021 election left the same man at the top, but knocked several bricks out of the political house he has built over three decades.

Twenty-five members of cabinet, including Vice-President Edward Ssekandi, lost their parliamentary seats.

And if this election showed us anything, it is that Ugandans do not suffer turncoats. Among those who were voted out are opposition-turned-NRM members who quickly earned themselves ministerial posts upon switching sides.

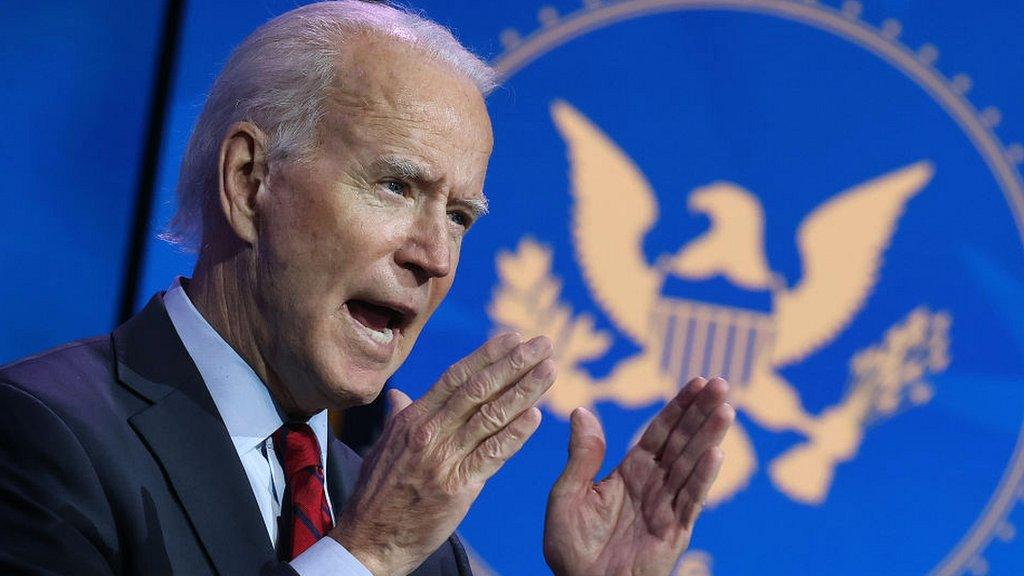

President Museveni spoke to his supporters from an open-top car as he entered Kampala after his win

In his victory speech, Mr Museveni nodded to the need to improve healthcare and education and promised to boost agriculture and manufacturing. He also lashed out at politicians who put their interests before those of the masses.

As for the NUP, its leaders are determined to go to court to challenge the result.

But that may be a struggle as Lina Zedriga, the party's vice-president for the northern region, said that its polling agents who had evidence of vote rigging have either been arrested or have gone missing.

'Not losing hope'

Nevertheless, she is patient.

"We will stay as long as we want change," she said.

"For as long as we want the true reflection of the will of the people of Uganda, we will remain resolved. We have waited for 30-something years. We are not losing hope at all."

The determination to hold on to hope will depend on whether the youth that Bobi Wine has fired up will be prepared to put themselves in harm's way.

Otherwise, the pattern of the last three decades will be repeated, with Mr Museveni and the NRM maintaining their stranglehold on power.

Related topics

- Published22 February 2021

- Published10 May 2021

- Published20 December 2020