Niger suffers deadliest raids by suspected jihadists

- Published

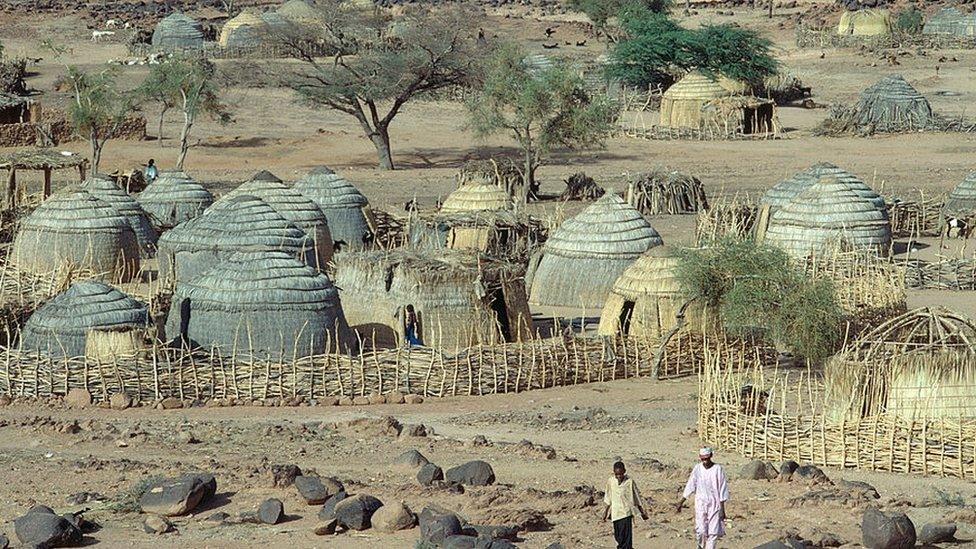

Remote villages in Niger have little security against attackers

The death toll from co-ordinated raids on three villages in Niger by suspected jihadists on Sunday has risen to 137.

"By systematically targeting civilians, these armed bandits are reaching a new level of horror and savagery," the government said.

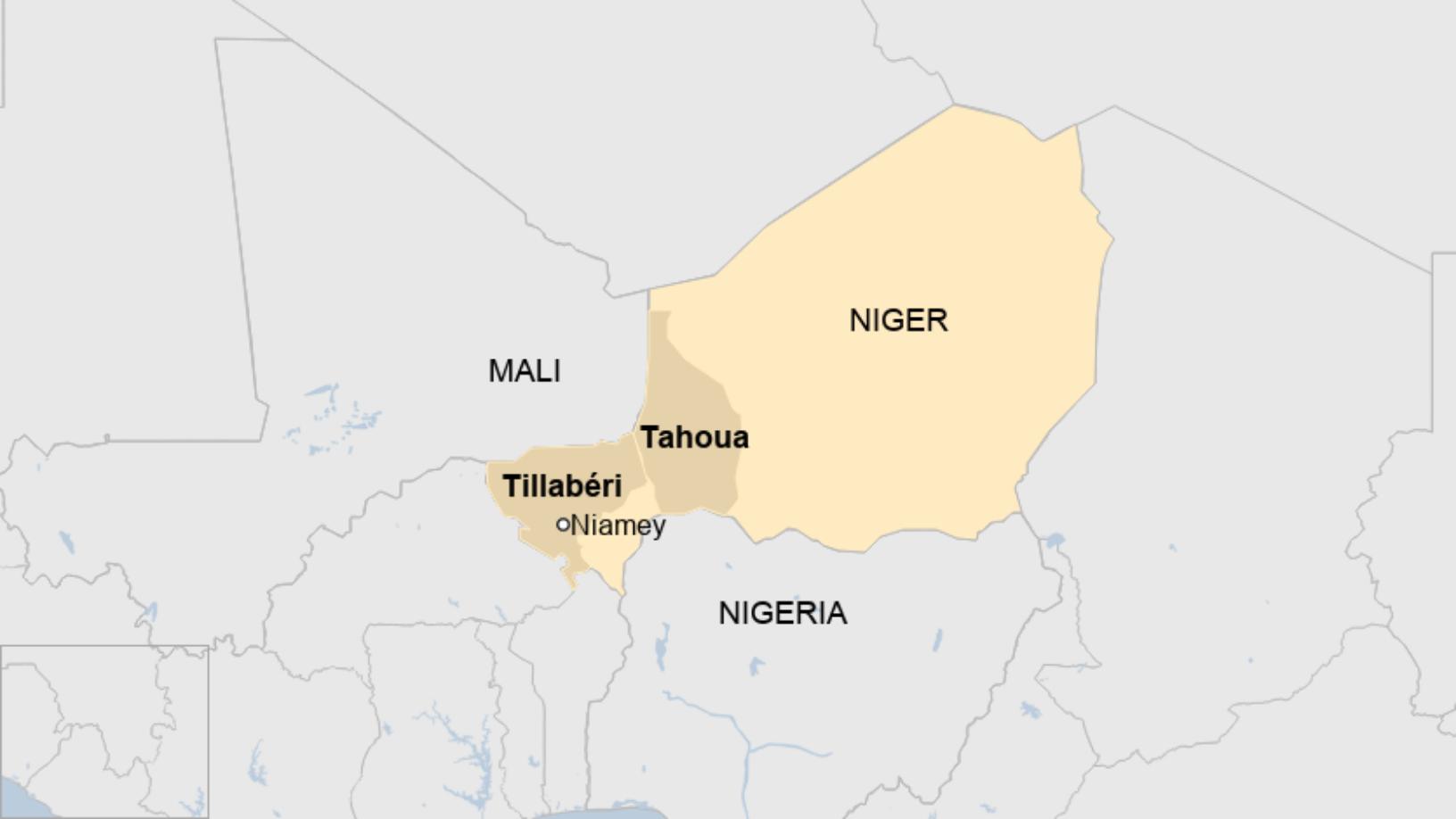

Earlier a security source blamed militants linked to the Islamic State (IS) group for the attacks in Tahoua region near Niger's border with Mali.

It is the deadliest massacre in Niger by suspected militants.

The West African nation is facing an upsurge in suspected jihadist violence, with an estimated 300 people dying this year in attacks.

Last week, at least 58 people returning from market were killed in Tillabéri region, also in the south-west near the Mali border, when gunmen targeted their bus.

Militants linked to IS and al-Qaeda are active in the Sahel region - a semi-arid stretch of land just south of the Sahara Desert which includes Mali, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

The Boko Haram group is also active on Niger's south-eastern border with Nigeria.

What happened?

In Sunday's attack in the Tahoua region it was initially thought that 60 people had been killed.

The gunmen, travelling on motorbikes, targeted the villages of Intazayene, Bakorat and Wistane.

They were "shooting at everything which moved", the AFP news agency quotes a local official as saying.

Adam Sandor, a Canadian academic who researches insecurity in the Sahel, told the BBC that most of those believed to be behind Sunday's raids were members of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) group, which is active in Mali and Niger.

There were also reports, he said, that militants from a Boko Haram offshoot - Islamic State West Africa Province (Iswap) - had provided reinforcements.

What do the militants want?

Dr Sandor said ISGS operated differently to other IS affiliates whose aim was to form a caliphate, a state governed in accordance with Islamic law.

Regional and international security forces have been unable to contain the Sahel insurgency

"Unlike those groups in the Middle East this group is extremely predatory and doesn't really provide any type of governance function to the population of the Sahel," he told the BBC's Newsday programme.

There is also an ethnic dimension to the conflict. Cattle raiding too is an element.

The communities from which ISGS gathers its support are mainly from the Tolobe clans of the Fulani ethnic group, says Dr Sandor.

"In this area of the borderlands - that community has been marginalised for several years - as a result they've grafted themselves on to local jihadist groups that have become ISGS."

This has meant that local militias have formed to defend themselves from ISGS.

"We can understand this attack as a sort of reprisal attack - score-settling violence - because of the collaboration those localised militias were providing to the Niger security and defence forces," Dr Sandor said.

Why are jihadists active in the Sahel?

The security crisis in the region started in 2012 - after the fall of long-time Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

It is suspected that jihadists were able to escalate insurgencies in countries like Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso thanks to weapons looted from Gaddafi's arsenal.

Weapons and drug smuggling along with fuel trafficking and cattle rustling are key to the survival of many groups.

French and other international troops, plus a large regional force, have been unable to contain the insurgency in the region.

Mohamed Bazoum, Niger's new president, won elections last month with a pledge to fight the insecurity caused by armed groups.

Related topics

- Published14 August 2023

- Published13 January 2020