Covid vaccine in South Africa: Behind the slow rollout

- Published

President Cyril Ramaphosa was among the first to be vaccinated in February but since then the rollout has hit problems

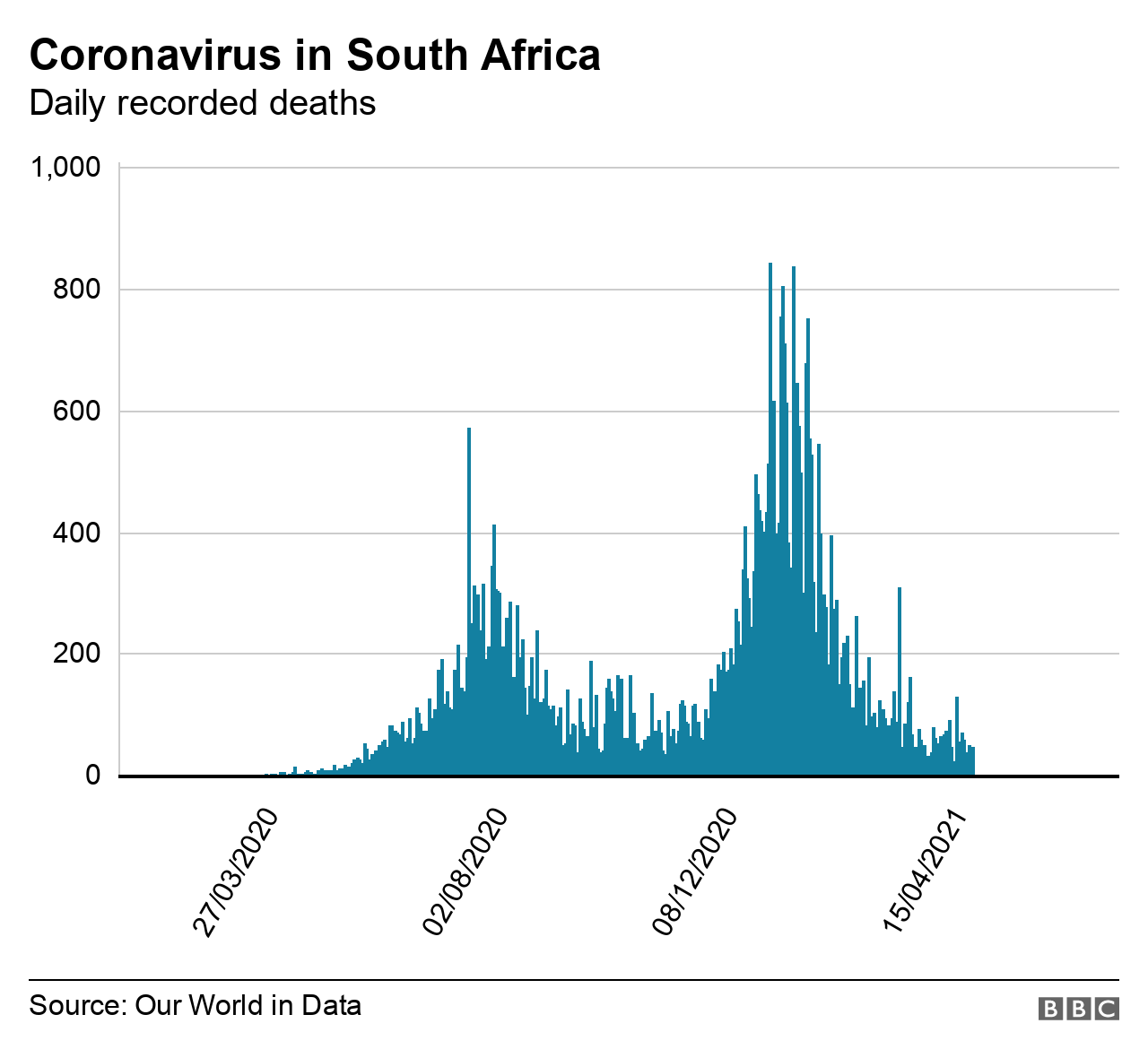

South Africa was swift to impose a strict lockdown and rigorous testing at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, but its vaccination programme can best be described as stuttering - despite it having the worst mortality figures on the African continent.

In January, the country appeared to be finally out of the blocks - and faster than other African countries when it came to getting hold of the vaccines - but the rollout has since faltered.

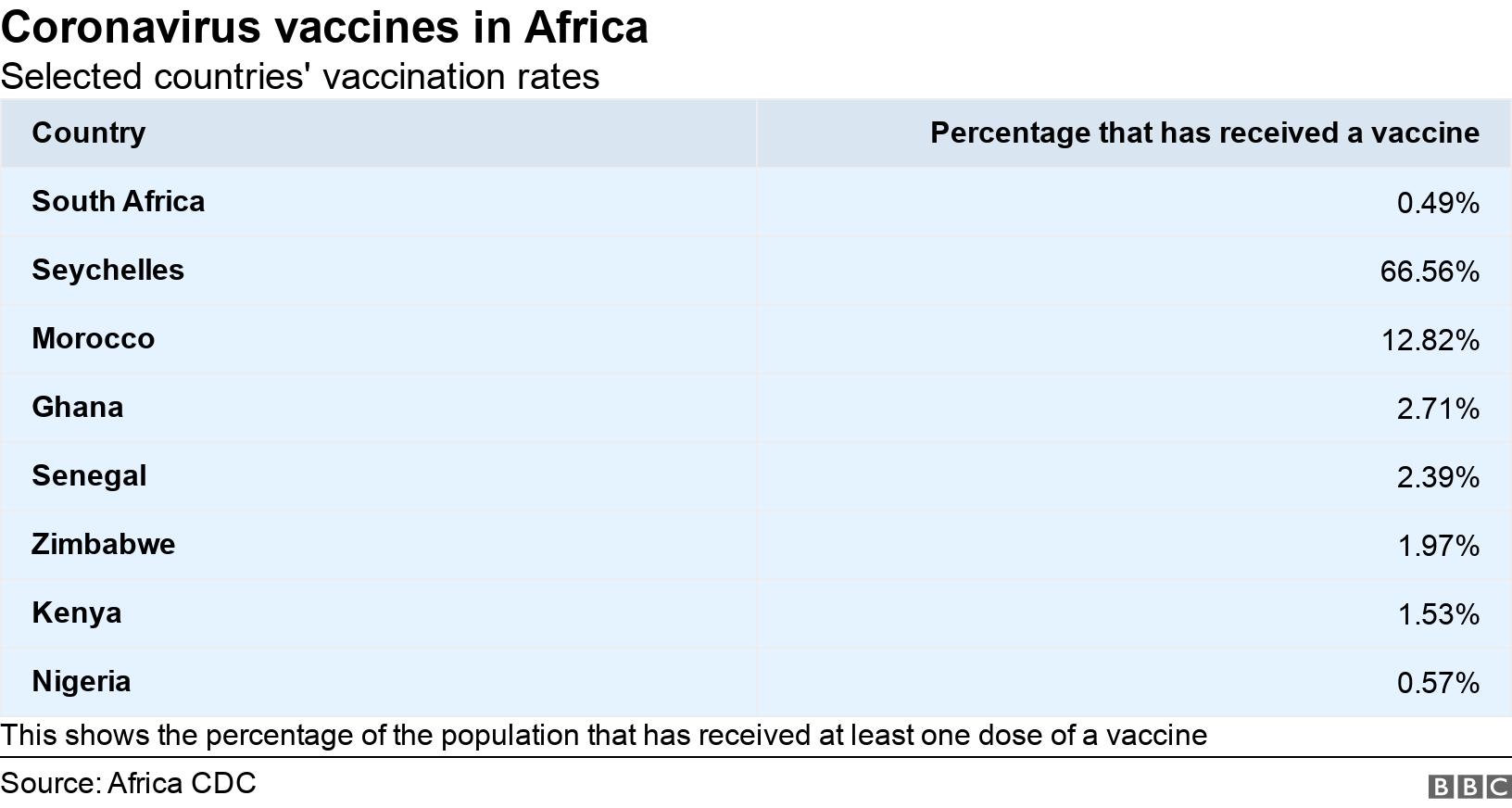

With only 0.5% of the population vaccinated, South Africa lags behind the likes of Senegal, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Zimbabwe and Botswana.

The government has had to push back its target of injecting 40 million South Africans, about two-thirds of the population, by December to next March.

And with winter fast approaching there are concerns about a third wave of coronavirus infections - particularly as not all frontline health workers have yet had a jab.

Critics say that had officials planned better, millions of South Africans - instead of just 300,000 - would be vaccinated by now.

Last year, the government talked tough about how seriously it was taking the virus and how closely it was following the science. Yet when it came time to securing vaccines, the country seemed to rely on getting them through the global Covax scheme.

The idea behind the initiative was to pool resources to support the development of vaccines with a view to ensure that all countries received a fair supply of effective vaccines.

But wealthier nations have seemingly stymied its effectiveness by doing deals with manufacturers guaranteeing themselves a supply meaning Covax has struggled to obtain enough doses.

AstraZeneca vaccines rejected

Covax aside, South Africa's vaccine programme had other problems.

The country eventually secured a deal in January to buy the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine from the Serum Institute of India, paying more than double the amount charged to the European Union.

Then in February a study in South Africa involving some 2,000 people found that the vaccine offered "minimal protection" against mild and moderate cases of the coronavirus variant that is most common in the country.

As a result, the vaccine programme was put on hold, and South Africa sold its one million doses to the African Union.

Selling our AstraZeneca vaccines was a miscalculation by our government; one that has set us back by several months"

Prof Shabir Madhi, who led the AstraZeneca trials in South Africa, said the sale was a mistake, as the vaccines already acquired should have been used for high-risk people.

"The AstraZeneca will still protect against severe disease, even if it didn't protect against mild and moderate case," local media quoted him as saying.

"Selling our AstraZeneca vaccines was a miscalculation by our government; one that has set us back by several months in terms of our vaccination rollout."

In February the country did become the first in the world to administer the single-dose Johnson & Johnson (J&J) vaccine after studies showed it had a higher protection rate against the South African variant than other jabs.

Johnson & Johnson delay

It was issued before its licence was granted as part of a trial, known as the Sisonke study, to vaccinate heath workers

Though this too hit a hurdle early in April when the US Food and Drug Administration suspended it after it found six people had developed a rare blood clot after having the vaccine.

South Africa followed suit, saying it needed time to consult local health experts on how to procced.

The vaccination programme was halted while the J&J vaccine was checked

The suspension was lifted later in the month, yet unlike the US, South Africa had not had the luxury of changing to another vaccine during the J&J suspension.

"The lesson here is to truly consider the benefit-risk ratio before taking such a decision," the Businesstech website quotes Prof Madhi as saying.

It is a sentiment shared by Dr Mvuyisi Mzukwa from the South African Medical Association, an advocacy organisation for doctors.

More on South Africa's Covid crisis:

"At the time of the US decision we had our own data from more than 200,000 health workers who were part of the Sisonke trial," he told the BBC.

"What the government should have done was look at that data first and see whether there had been any reports of a similar problem instead of simply copying and pasting what the US were doing and stopping the trial abruptly."

'Delays create suspicion'

Dr Mzukwa is concerned that the way the J&J issue was handled may contribute to vaccine hesitancy.

"It may cause more suspicion now. The government will need to make a concerted effort to assure communities, in their own language, that the vaccine is safe to take. If they don't, we may find ourselves facing vaccine hesitancy and we can't afford that in vulnerable communities."

And some do have the jitters, like Johannesburg-based insurance salesman Langa Mavuso, who told the BBC he would not get the injection unless it became mandatory, despite the World Health Organization saying the vaccines are safe, with some experiencing only mild side effects.

"I personally don't want to be the first to get the vaccine. What if there are irreversible problems?"

Even physiotherapist Donna Dudley, whose family has a history of blood clots, is nervous but may get the injection to protect her patients.

For Johannesburg estate agent Eniel Noeth it all comes down to safety: "I'm happy about the delays because I believe that testing still continues during this time and hopefully when improvements have been made to the vaccines."

Health Minister Dr Zweli Mkhize denies that the pauses were an overreaction and rejects accusations that the vaccination programme has been haphazard.

Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines started arriving in South Africa earlier this week

And he does not foresee further delays, recently announcing that the country had now secured a total of 51 million jabs from various manufacturers to be delivered in tranches during the course of the year:

J&J - 31 million (single dose required)

Pfizer/BioNTech - 20 million (two doses required) - the first batch arrived on Sunday night and a local drugs plant will also start releasing the vaccine later in May.

The vaccinations will then be done in three phases:

From beginning of May - all health workers not already jabbed

From 17 May - people aged over 60 and those with other health problems

From around November - the general population.

But for some, the plan is just too slow.

Reality Check:

"Hundreds of people come in and out of the shop every day. Yes we take measures to protect ourselves but I want the vaccine so I'm sure I've done everything to protect my family," Thembeka Mnisi, a retail store manager and mother of two, told the BBC.

Prof Thumbi Ndung'u, deputy director of the African Health Research Institute, says there is an urgency in light of new waves and mutations.

"We need to be vaccinating people at a much faster rate than we are doing currently," he told the BBC.

"It is important that our government learns some lessons from other countries such as India on how devastating this virus can be."

Related topics

- Published15 July 2020

- Published24 August 2020