Jacob Zuma: South Africa's ex-president pleads not guilty for multi-billion dollar arms deal

- Published

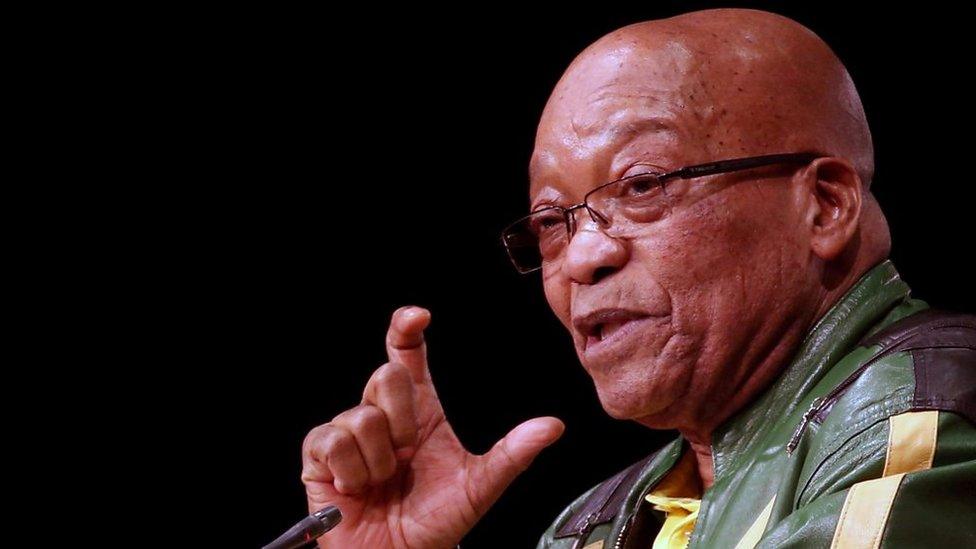

Mr Zuma blames "enemies" in the the African National Congress for his legal troubles

Jacob Zuma, the former South African president, has pleaded not guilty in a corruption trial involving a $5bn (£3bn) arms deal from the 1990s.

He is facing 16 counts of racketeering, corruption, fraud, tax evasion and money laundering.

Mr Zuma blames political enemies in the governing African National Congress (ANC) party for his legal troubles.

The arms deal involved buying new fighter jets, helicopters, submarines and warships.

But questions emerged about the deal months after it was signed, with some critics saying the government should have spent the money on fighting poverty.

Mr Zuma was South Africa's president from 2009 until 2018 when he was forced to resign after a vote of no confidence.

On Wednesday crowds gathered outside the courthouse in Pietermaritzburg city in KwaZulu-Natal province to cheer on Mr Zuma, who still enjoys some popular support.

The former president's defence team called for the removal of state prosecutor Billy Downer, on the grounds that he had "no title to prosecute".

But the presiding judge ruled that the matter would be dealt with on 19 July.

A defining moment for South Africa

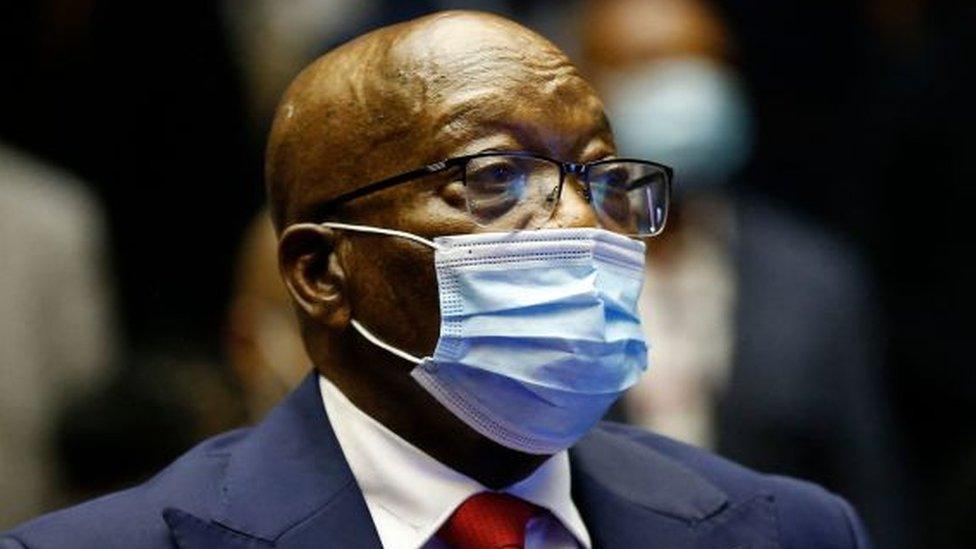

Jacob Zuma looked frail and spoke quietly as he stood in the dock to enter a plea of "not guilty".

This was a moment he had been seeking to avoid for decades, but South Africa's former president is a politically weakened force these days and his legal options have now run out.

It's not clear how long this trial will last, or what the outcome might be. But regardless, this is a deeply symbolic and defining moment for South Africa.

Mr Zuma is now on trial - and is likely to face many other legal challenges in the coming months.

Many of his most powerful allies in the ANC are also facing similar legal problems.

This tips the balance of power in the governing party firmly towards President Cyril Ramaphosa and his campaign to clean up the party and fight corruption.

Powerful ANC critics of Mr Zuma openly refer to him as a "gangster-like figure" who nearly broke this country's young democracy and they warn of a long struggle ahead to undo that damage.

Why was there an arms deal?

Newly democratic South Africa decided its military needed to be overhauled - and five years after coming into power following the end of white minority rule, the ANC government signed contracts totalling 30bn rand ($5bn; £3bn in 1999).

The deal involved companies from Germany, Italy, Sweden, Britain, France and South Africa.

Why was it controversial?

Even before the allegations of corruption, the spending of billions of dollars on new fighter jets, helicopters, submarines and warships was contentious in a country where millions lived in poverty.

Others also pointed out that there was no credible threat to South Africa's sovereignty to justify the spending.

Questions emerged within months, leading to official investigations into allegations of conflict of interest, bribery and process violations in the purchasing of equipment.

What was the outcome?

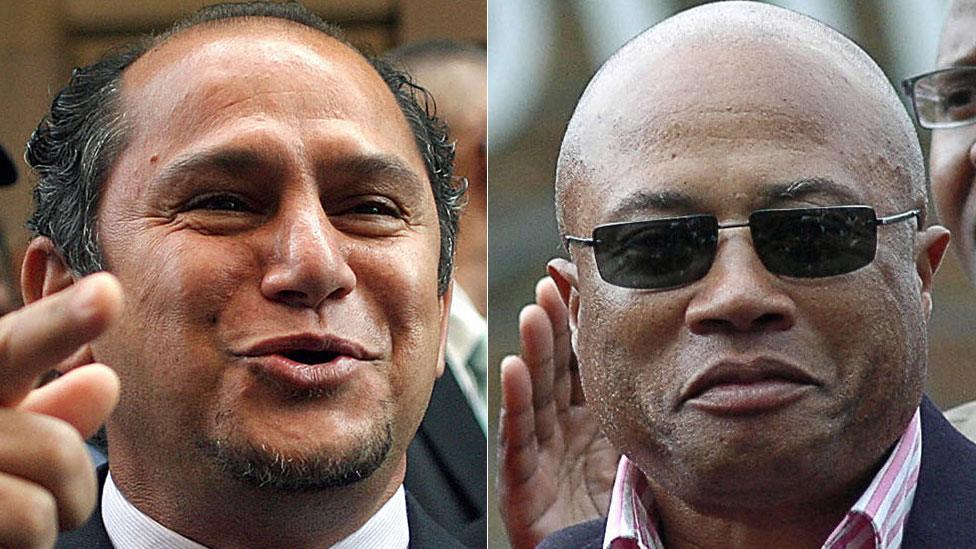

Schabir Shaik (l) spent four years in jail and Tony Yengeni (r) served five months

There have only been two convictions:

The ANC's chief parliamentary whip at the time, Tony Yengeni, was found guilty of fraud after it emerged he had received a large discount on the purchase of a luxury car from one of the firms bidding for a contract. He also lied to parliament about the benefit. After various appeals he was jailed in 2006, although he only served five months of his four-year sentence, external.

Financial adviser and businessman Schabir Shaik was jailed for 15 years in 2005, external for soliciting a bribe on behalf of Mr Zuma from Thint, the local subsidiary of French arms company Thales. He was released on medical parole in 2009.

The allegations also formed part of US and British inquiries into BAE Systems. In 2010 the UK military contractor pleaded guilty to charges of false accounting and making misleading statements and paid more than $400m in penalties to end the investigations into questionable payments made to win contracts.

The following year Swedish firm Saab admitted that 24m rand was paid to secure a contract for fighter jets, but said the payments had been made through BAE Systems.

A new South African commission of inquiry into the deal, formed in 2011, concluded in 2016 that no new charges should be brought.

But a week later the High Court ruled, in a case brought by the opposition, that Mr Zuma should face charges over the deal. They had been dropped weeks before he became president in 2009.

What is Mr Zuma's alleged involvement?

The arms deal, among other scandals, dogged Jacob Zuma's presidency

He is alleged to have received bribes from a French arms firm via his financial adviser in order to protect Thales from scrutiny.

He was first charged in 2005, but a trial has never come to fruition - thanks to many challenges, other technicalities and backing from a strong faction within the ANC.

But the arms deal, among other scandals, dogged his presidency.

In 2018, the Supreme Court backed the decision that charges be reinstated and he now faces 16 counts of corruption, racketeering, fraud and money laundering. In total, he is accused of accepting 783 illegal payments.

Why did the courts order the charges be reinstated?

Jacob Zuma still has many supporters despite his legal problems

A High Court judge said the decision by the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to drop the charges in 2009 was "irrational".

The NPA had done so after receiving phone-tap evidence from Mr Zuma's lawyers, which suggested there had been political interference in the investigation.

But the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) pursued the case after Mr Zuma became president, winning a court battle to make the sealed recordings public and then arguing there was no evidence to warrant the charges being dropped.

Zuma arms deal timeline

October 2005: Charged with corruption

September 2006: Trial is struck from the court list when the prosecution asks for yet another delay to gather evidence

November 2007: The court of appeal opens the way for charges to be brought again when it rules that the seizure by police of incriminating documents from his home and office was legal

December 2007: Ten days after Mr Zuma becomes ANC president, prosecutors bring new charges of corruption, racketeering and tax evasion

September 2008: A judge declares that the prosecution was invalid and throws out the charges on a legal technicality

January 2009: Appeals court overturns the ruling, just months before general elections

April 2009: The chief prosecutor drops charges against Mr Zuma after phone-tap evidence suggested there had been political interference

April 2016: High Court rules Mr Zuma should face the charges and prosecutor's decision was "irrational"

October 2017: The Supreme Court backs that ruling

April 2018: He is charged with corruption - two months after resigning as president.

May 2021: Mr Zuma pleads not guilty as trial resumes

Related topics

- Published6 April 2018

- Published6 April 2018

- Published15 February 2018

- Published6 April 2018

- Published14 February 2018

- Published6 February 2018

- Published15 December 2017

- Published16 March 2018