Mozambique Palma attack: 'I had to pay a bribe to flee'

- Published

Farida spent 10 days living in a forest after the attack

People desperate to flee a town in northern Mozambique following a jihadist attack have had to pay bribes to leave after security forces set up roadblocks, trapping thousands, the BBC has been told.

There are growing fears of a humanitarian emergency in the area where aid agencies have not been given access.

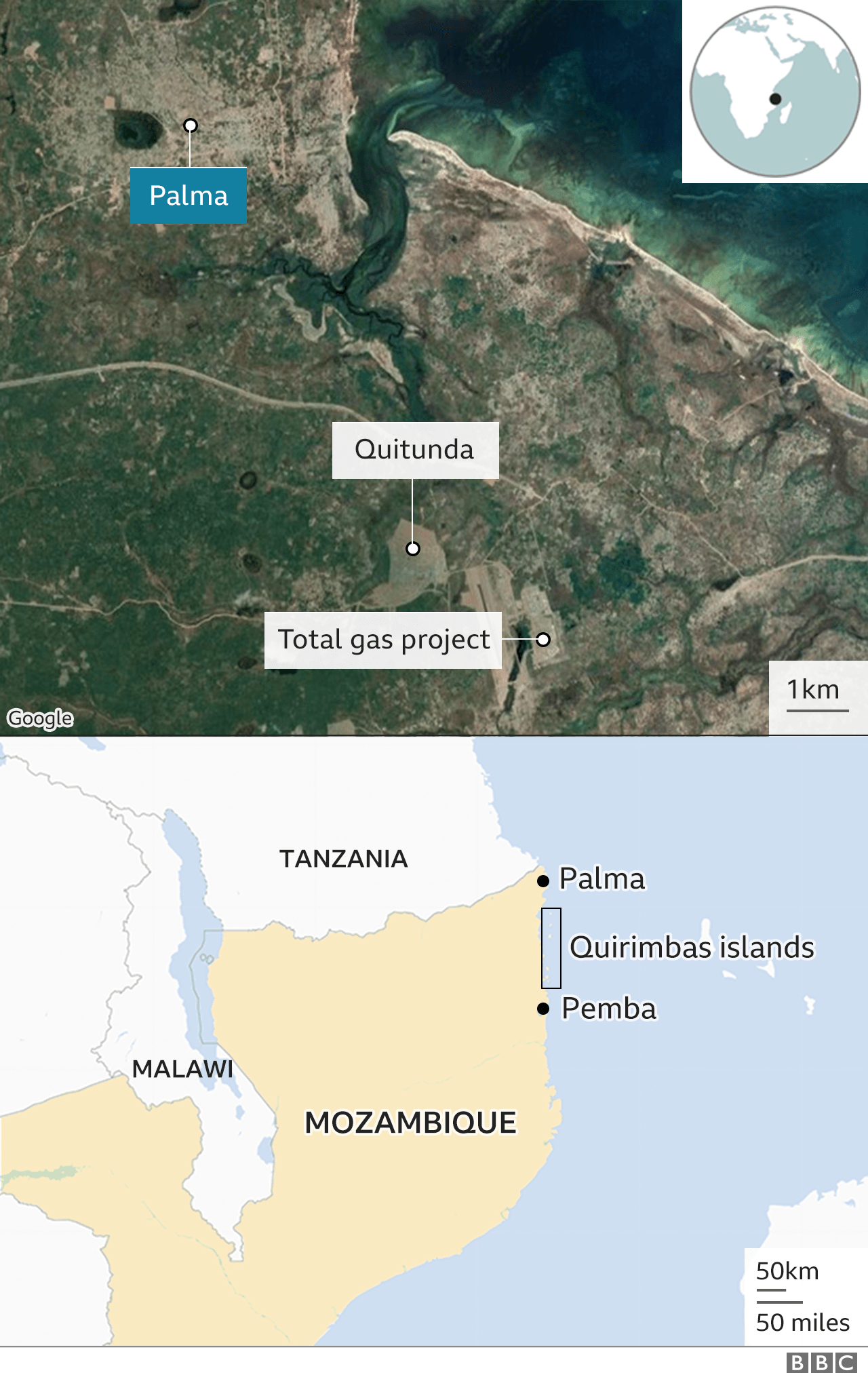

Checkpoints surround the village of Quitunda near Palma, where more than 20,000 people sheltered in the days after the strategic town was overrun by jihadist militants.

Al-Shabab - a homegrown militant group - started its insurgency in Mozambique's resource-rich Cabo Delgado region in 2017. Two years later it pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) group although it is not clear how close the links between the two organisations are.

More than 2,800 people have been killed during the insurgency and nearly 700,000 people forced from their homes.

The group's most dramatic attack was on Palma, a once-sleepy coastal town, that was being transformed into a hub for a burgeoning gas industry. It lies 10km (six miles) away from a liquified gas plant, operated by the French energy giant Total, worth $20bn (£14.5bn) - Africa's biggest foreign investment project - which is now on hold.

'I had to leave my husband behind'

When the militants attacked the town on 24 March - from its outskirts and with infiltrators who had entered the town - Farida, her husband and five young children fled to a forest. "We stayed for 10 days in the woods," she tells me.

Witnesses talk of seeing Palma's streets strewn with beheaded bodies, while some of the dead had also been hacked to pieces.

Thousands have fled to the island of Quirimba to escape Mozambique's Islamist insurgency

The family then joined thousands who ran to the gates of the Total gas plant.

According to the company, some 23,000 people had reached their gates by early April.

An assessment in April by the United Nations' International Organisation for Migration found 11,104 people living in the compound of EPC de Quitunda, a school close to the gas installation.

The report says the "internally displaced persons are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance. Thirty per cent of the households are currently sleeping outdoors, whilst the remaining 70% currently live in makeshift shelter".

Farida, whose name we have changed to protect her identity, was desperate to get her family out of Quitunda. With limited options to escape - either a boat journey of several days or military evacuation flights - her husband managed to raise 5,000 meticals ($80; £60) to get her and their children put on a list for departure and then onto a plane out. The emergency flights are meant to be free.

"At the beginning they didn't charge pregnant women, sick and children. Then they started carrying people who were on the list," she says.

I met Farida in the regional capital Pemba, where she's still struggling to look after her children, although she is relieved that they are out of harm's way. Hadijah, whose name we have also changed, is in Pemba too - she also admits to paying 5,000 meticals to board an army flight.

"We had no money and we were hungry and the children were sick. To leave Quitunda, I spoke to my husband and he spoke to his boss, who sent us the money via M-Pesa [mobile money transfer]," Hadijah tells me.

The two women say that there are many more left behind unable to leave, including Farida's husband.

Human Rights Watch (HRW), a campaign group which has been interviewing survivors from the Palma attack, says it's also spoken to people who admit to paying bribes to board evacuation flights or to get on to boats to leave Quitunda.

"Can you imagine people that have no food, nothing to buy, that have lost everything during this conflict being forced to use the last money they have to be able to board their relatives on to a plane and be taken to safety?" says Zenaida Machado, a senior HRW researcher.

The BBC approached Mozambique's Ministry of Defence about the allegations that displaced people are having to pay bribes to flee Palma, but it has not responded.

'Dynamic situation'

We asked several international aid organisations to speak about the unfolding humanitarian crisis in Quitunda and the wider Palma district and the fact that for now they cannot access the area. Two global agencies told us they could not speak on the record because they did not want to jeopardise delicate negotiations with the government.

Some local aid groups have managed to reach people stranded in Quitunda

The World Food Programme (WFP), which offers relief to more than half a million people displaced by the Islamist insurgency in north-eastern Mozambique, says it is working with the government to ensure the right security conditions on the ground.

"There are people in urgent need of humanitarian assistance in Palma and Quitunda," acting WFP country director Pierre Lucas told the BBC.

"WFP requires safe humanitarian access to reach the people most in need. There is a situation probably on the ground that is still dynamic and my understanding is that it's a work in progress."

Humanitarian workers based in Pemba have told the BBC they are worried about the lack of medical support in Quitunda as the only clinic is barely functioning.

Two months after the attack on Palma, there are concerns families are running out of food, with survivors who have made it out telling stories of widespread hunger.

You may also be interested in:

Communication lines to Quitunda have been mostly off since the end of March and it's hard to speak to people on the ground.

The police and army did not grant permission to the BBC to access the area.

But a military source told us the government was stopping people from leaving because of concerns insurgents had infiltrated those displaced - and evacuations could allow them to spread easily across the region especially to the regional capital.

"The government's main obligation is to protect its people and not hide behind excuses like insurgents are mixed up with the population and there's no safety for humanitarian agents to go there," Ms Machado says.

"If there's no safety for humanitarian organisations to go to Palma, then that safety doesn't exist also for people to remain there. They [the government] should step up their efforts to evacuate those who want to leave Palma, for free, immediately."

At the weekend President Filipe Nyusi told his party's members that security forces had stopped an attack on Olumbe village, also in Palma district.

There are regular reports of shooting in Palma and fires in the night. Many believe that those in Quitunda could get caught up in future attacks.

The Mozambican defence ministry has not responded to BBC questions about why people are not allowed to leave Quitunda and what security challenges are preventing aid organisations from getting to the area.

Nearly 60,000 people have fled Palma since the attack in March, accelerating an already worsening humanitarian situation in the Cabo Delgado region.

In April last year 172,000 people had been displaced by the fighting - that number is now about 700,000.

'I lost my baby'

Nearly 33,000 of them are sheltering on the paradise islands of the Quirimba archipelago just off the coast of Mozambique in the Indian Ocean.

The soft white sandy shorelines surrounded by azure-blue waters used to be a popular destination for international tourists who paid hundreds of dollars a night to stay at luxury beach hotels.

Quirimba is now home to refugees, rather than tourists

Today, on one of the islands - Quirimba - rows of white tarpaulin tents line the white sandy beaches. We are the first international journalists to arrive here since the attack on Palma. More than 9,000 people from different parts of Cabo Delgado are seeking shelter here.

Thirty-two-year-old Mamo Sufo from Palma and her three young children arrived at the island just days before we did.

By this point, it was nearly two months since the town was overrun but she's spent all that time travelling to Quitunda and other villages before taking a boat to Quirimba where she hopes other family members will join her.

She started her journey seven months pregnant, but while out at sea she went into pre-term labour and her son died.

Mamo Sufo spent two months before she reached safety

"The weather and the conditions of the boat accelerated the arrival of the baby and there was no help during the delivery. He had health complications just after he was born," she told us.

Out on the islands the relative safety from the fighting has allowed aid organisations to offer food, shelter and medicine.

But the number of people in need in Cabo Delgado is growing fast, outstripping government and humanitarian agencies' resources.

Related topics

- Published17 April 2021

- Published4 April 2021

- Published29 March 2021

- Published2 June 2018

- Published29 March 2021

- Published25 October 2024