Rediscovering the African roots of Brazil's martial art capoeira

- Published

Brazil is well known as the home of the dance-like martial art capoeira, but its roots in fact lie across the Atlantic. In Angola, one man is trying to resurrect an older style to help people reconnect with their heritage, writes Marcia Veiga.

Three times a week, in the late afternoon heat Lucio Ngungi gets buzzed into a bright coral compound in Angola's capital, Luanda.

He follows the footpath to the small basketball court, which, as the sun starts to go down, echoes to the sound of clapping, singing and drumming, led by musicians.

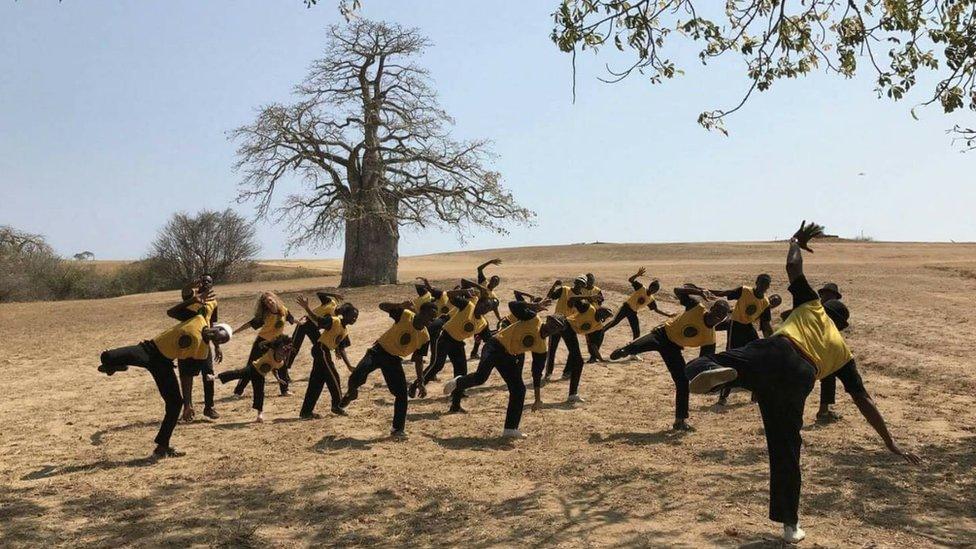

Encircling them, protectively, students, wearing yellow T-shirts that display traditional masks are eagerly waiting to step into the middle in pairs.

In synchronicity, they begin swinging low left to right, in a move known as the Ginga.

Among them, almost trance-like, is Ngungi, the leader, lost in the chant: "There is no more or less, there is just different knowledge."

This is Capoeira Angola, a version of the martial art that is rarely practised either in Brazil or Angola itself.

But its name speaks to the origins of the art that reaches back centuries - before people were enslaved and transported from the southern African coast to South America.

The music plays a key role in capoeria

It was developed in what is now Brazil using rhythms and call-and-response singing found in the African traditions. The inclusion of instruments was crucial for distracting onlookers.

African influence downplayed

Capoeira Angola has a ritualistic feel and the movements are predominantly low to the ground, with the focus on precision. This is why the music is slower than in the dominant version, known as Regional.

The difference between Capoeira Angola and Capoeira Regional is subtle, but Capoeira Angola includes more instruments and its practitioners feel it is more spiritual.

Ngungi's mission is to make this version more popular again.

Nearly two decades ago, he started training in Capoeira Regional, but after seven years, he heard about Capoeira Angola and instantly knew Regional was no longer for him.

"I constantly asked myself, why would I keep training Regional when I can go to the roots of my country?" the 36-year-old said.

I sometimes feel a little angry when I think about how Angola's contributions to capoeira get dismissed"

With limited information available, he sought out Brazilian Pedro Trindade - otherwise known as Mestre Moraes - who he had learned was the Capoeira Angola master responsible for resurrecting it in the 1980s.

"I sometimes feel a little angry when I think about how Angola's contributions to capoeira get dismissed," Ngungi says.

Mestre Moraes says the African influence was deliberately downplayed, partly because of racism.

"It was recognised as a part of African culture and labelled as aggressive because of the slave association," he explains.

Capoeira was originally developed as a way to make it appear that people were dancing

In the mid-16th Century, while working in the fields, slaves created what later became Brazil's earliest form of capoeira, disguising fighting techniques as folk dancing.

Following the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888, the government banned capoeira, fearing its use could make any revolt by freed slaves more difficult to overcome.

It went underground, and many black people continued to practise what is now recognised as Capoeira Angola in hidden spaces, using nicknames to protect their identity.

Around 1930, Reis Machado, better known as Mestre Bimba, developed a way of teaching capoeira that made it easier to learn.

Then after persuading the authorities about the cultural value of the martial art, the ban was lifted, and he opened the first capoeira school in Brazil.

However, capoeira was still looked down upon, especially by upper-class Brazilians.

In response, Mestre Bimba set new standards - he introduced clean white uniforms, required students to show good posture and brought in a system of grading.

As a result, capoeira began to attract a new audience who became interested in practising capoeira indoors.

This was the beginning of Capoeira Regional.

Capoeira Angola has a slower pace than Regional

As some practitioners continued to follow the older form, they agreed on the name Capoeira Angola to differentiate it. But over time it was marginalised and largely forgotten.

Regional has a faster pace than Capoeira Angola. Mestre Bimba also simplified the use of instruments relying on only the panderios (tambourine) and one berimbau (bowed instrument).

'It relieves my anger'

Despite the name, the claim that capoeira originated in what is now Angola remains a matter of speculation, as the slaves that left the Luanda docks came from across southern and central Africa.

It has, however, been linked to Angolan traditions like N'golo - where two young male combatants mimic the movements of fighting zebras to compete for the hand of a bride.

But whatever the exact background, Ngungi was determined to reconnect to a history that preceded slavery and instil pride about their past into Angolans.

He went into exile at the age of 15 during Angola's civil war, but on his return in 2014 he wanted to help bring about change in the country.

Ngungi became a social worker, and also opened the country's first Capoeira Angola school, the Escola de Capoeira Angola Okupandula, which means "thank you to you and your ancestors".

I feel proud to take part in something so liberating that stemmed from slavery, as a free man"

He earned the rank of Contramestre, and has a small but keen cohort of students.

The hypnotic sounds of the instruments - agogô (bells), atabaque (drum) and berimbau drifting across the school's neighbourhood have acted as a magnet.

"I was peering out of the veranda trying to figure out where the sound was coming from when I first saw the Contramestre," says Kelly, a 17-year-old student.

Similarly, Marcos, 18, discovered Capoeira Angola through hearing the rhythmic playing from his balcony five years ago.

"I train Capoeira Angola five days a week and love how it relieves my anger, helps me find balance, cope with stress, and forget the outside world," he says.

The notion of teaching students about Angola's historical significance outside European culture is imperative at the school.

'Part of something bigger'

"I've learnt more about my culture and country through Capoeira Angola than at school," says the youngest student Aguinelo, 15,

Mestre Moraes compares Capoeira Angola to the infinity symbol, reflecting that inside the circle the capoeirista feels there are no boundaries or authority.

"It teaches you that you're a part of something bigger," he says.

Ngungi's students are living proof of this.

"I feel proud to take part in something so liberating that stemmed from slavery, as a free man," says Marcos.

Ngungi's dream is to one day buy enough land to build an academy and to keep inspiring the youth using Capoeira Angola.

"I care a lot about my people and constantly remind myself that giving back isn't an obligation but a duty."

- Published26 November 2014

- Published24 July 2020