Ghana's Kojo Marfo: Sell-out show for butcher-turned-painter

- Published

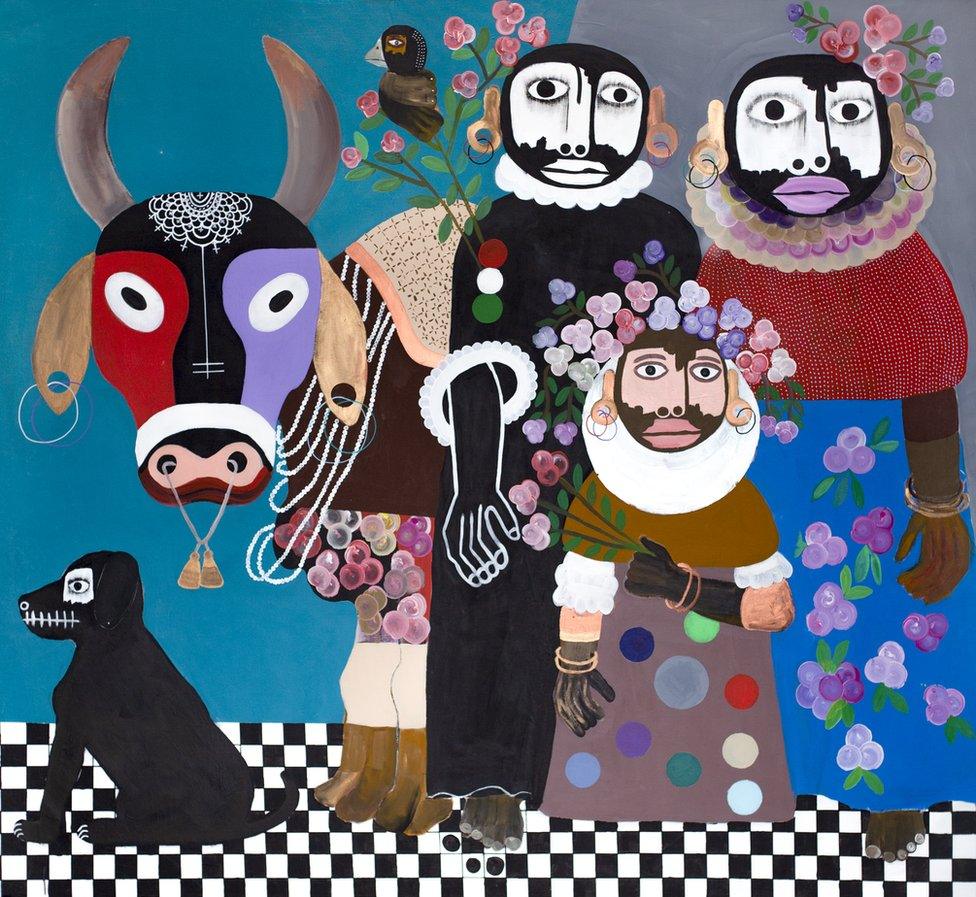

Kojo Marfo is a butcher-turned-artist determined to tell the world about the importance of cows.

"The cow builds civilisations," says Marfo. "In Ghana we use them to plough the land and if you have two to three animals, you can get a beautiful woman to marry you. In parts of India they are treated as Gods."

His appreciation began in childhood in rural Ghana, where he was raised by his mother and grandma, and it grew after moving to New York for work where he fell into a short-term career as a butcher.

"I was actually hopeless. I knew so little about meat, I'd cheat," says the 41-year-old.

"On the wall there were anatomical drawings of the animals detailing each cut and I'd have to use those as a guide. Even then, my boss would catch me and all I would be doing is chatting to customers."

He may have once sold their flesh, but his bovine-inspired canvases now fetch three times their asking price. Marfo's work now graces a range of designer scarves by Aspinal of London.

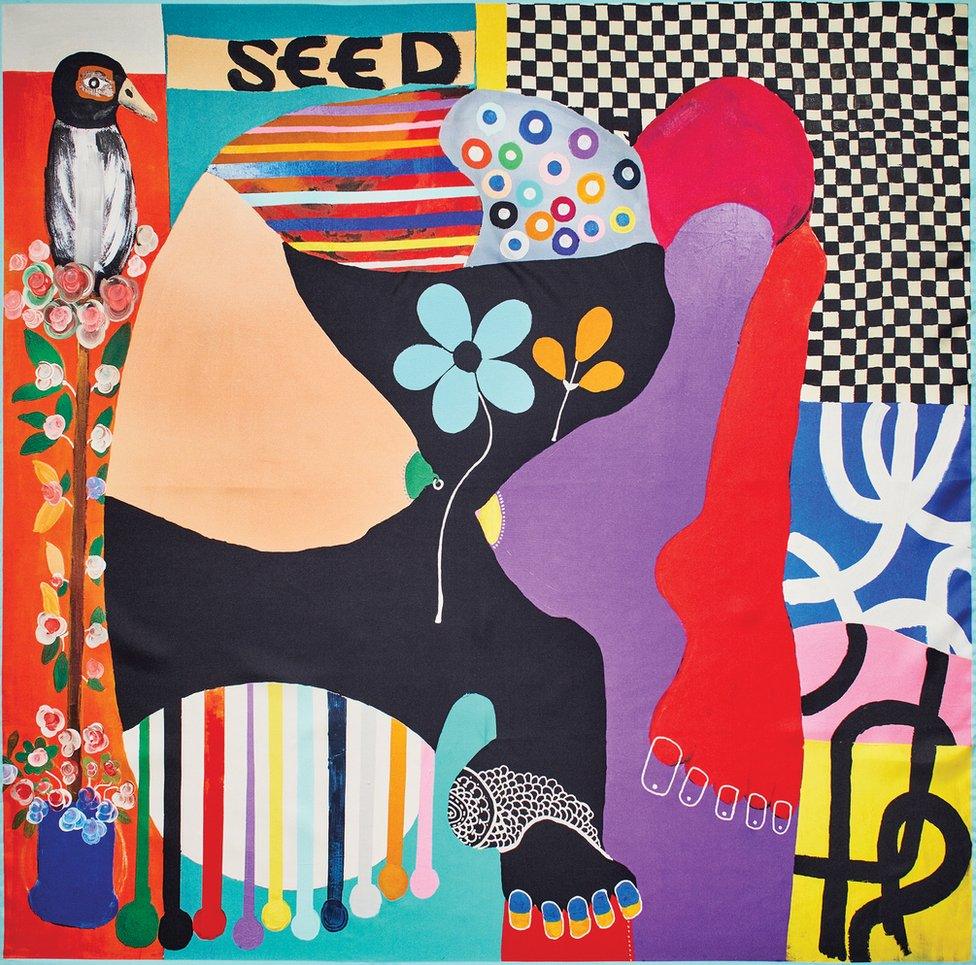

Other topics close to the artist's heart are the power of womanhood, the value of single parenting and the beauty of vitiligo.

His work at first glance feels vividly African - he grew up in the mountainous town of Kwahu, about four hours from Accra - but each piece is a careful patchwork of different continents.

Renaissance ruff collars from Britain, sacred cows from India and fertility dolls from Ghana all feature.

"We live in a great melting pot - it has many cracks in it," he says. "But I want to bring people together and for everyone to see their culture reflected."

Marfo remembers spending his formative years in the local library looking at pictures of Picasso and watching the craftsmen of Accra sell their wares to tourists, but says his own artistic ambitions initially got no further than the riverbank.

"I felt I should be becoming a doctor or an accountant, but I would go to the river's edge and collect the tough clay or get berries and crush them into dyes.

"I would put Vaseline on paper to create tracing paper to trace from art books or magazines. But it wasn't until I left Ghana that my work became serious."

Eventually he found his way from New York to the UK, where he worked in his aunt's grocery shop in London.

During the 2000s Marfo admits he gave up on his art but was drawn back in once inspiration returned.

"I wanted to show how positive a single-parent lifestyle could be," he says.

"In the mountains, women are the hardest-working people there and women alone raised me. A staunch feminist once told me that men were always in charge, that women were always victims. But women are always in charge where I'm from."

His work also began to toy with ideas of beauty - giving all his characters vitiligo on their faces. The medical condition sees paler, unpigmented patches develop on a person's skin.

"The faces, which look like a collage cut, I got those ideas from a person that I know that had vitiligo," Marfo said in a recent interview, external.

"When I tried it, it worked for me. I always say to myself that I don't want to paint beautiful art... I just want to paint something that I could use to talk about issues."

Being raised by a Jehovah's Witness mother also fed his curiosity about religious symbolism.

"An African understanding of art is completely different to Europeans'. Europeans can play with art and express themselves but, in Africa, they look at it from a different angle.

"If you paint a beautiful figure, a man or a woman or nature - it is accepted. But the moment you delve into spirituality and voodoo, everyone says: 'This guy is dangerous!' Even good friends will say: 'How can you reference these things, you cannot play with this stuff'."

Marfo began selling pieces online, then sent his work to an open call-out for developing artists, called Isolation Mastered.

Their vibrancy and edge caught the attention of judges - including Sotheby's art historian David Bellingham and art collector and Gavin Rossdale, from British rock band Bush, who bought one of Marfo's paintings for his personal collection.

Suddenly all of Marfo's work was selling.

"I don't know if it was because of the Black Lives Matter background," says Marfo.

"I hear two things from buyers: They see something different in my work - 'there's no-one doing what you're doing,' they say - and they like the personal stories I attach to them."

Such stories include Coronation, which features a couple staring intently ahead. You notice on second glance that the female figure is wearing a boxing glove clenched into a fist. This, says Marfo, is an ode to a woman he knows who discovered her partner was having an affair during lockdown.

At his first exhibition at London's JD Malat Gallery, all of his works sold out in the first month. At his second exhibition, Dreaming of Identity, all of his works were snapped up by the end of the first day.

But Marfo, a boy from the mountains, cares nothing for the money. It's all about getting by.

"In Kwahu the land is no good for growing things, so you learn to make your own way. In Ghana, if you are from Kwahu, you are considered a money-grabber but I've always been made to feel grateful just for what was in my pocket."

And he hasn't entirely written off swapping his paintbrush for the butchers' knife again either.

"I am still fascinated by the work of butchers, I'd like to learn the skill and do it properly."

Additional reporting by Natasha Booty

Kojo Marfo's Dreaming of Identity is currently showing at the JD Malat Gallery in London

Related topics

- Published7 July 2021

- Published2 December 2020