Central African Republic war: No-go zones and Russian meddling

- Published

Russian personnel have been helping government troops

Amid a Russian-backed advance, the growing threat of landmines and improvised explosives in the Central African Republic (CAR) points to a dangerous tactical shift in a new and unfolding guerrilla war.

Earlier this month, a convoy driving across CAR's volatile north-west struck an explosive device, killing an aid worker from the Danish Refugee Council.

Even in one of the world's most dangerous countries for aid workers, who routinely face violence and intimidation, the tragic incident stood out - highlighting a growing and unprecedented threat after years of civil war.

These indiscriminate devices, which can kill or cause horrific injuries, are keeping aid and human-rights investigators out of hotspots - and leaving desperate communities without a lifeline.

"Fighting is happening behind closed doors," said Christine Caldera, from advocacy group the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, adding that it was civilians who were paying the price for the increasing use of explosive devices.

Documented atrocities

While instability has wracked CAR for decades, the origins of this new chapter in the crisis stretch back to 2013 when a rebel coalition seized power, triggering reprisals from militias loyal to the ousted regime amid a spiral of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

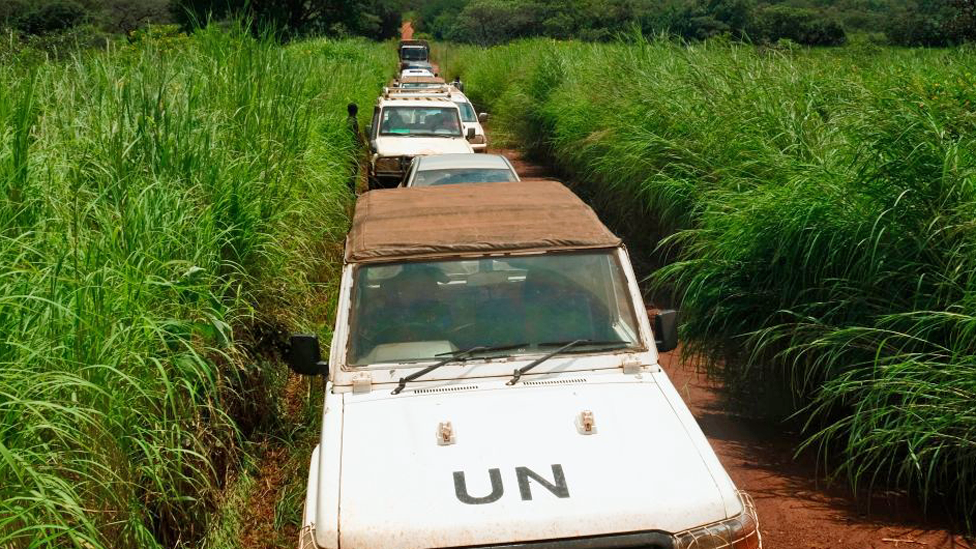

Areas of the north-west have become inaccessible to the UN and aid workers

As the warring parties fragmented, Russia entered the fray in 2017 as part of efforts to expand its influence across the continent - backing the beleaguered government in the capital, Bangui, and giving it weapons, ammunition and 175 military instructors.

Evidence suggests these so-called instructors include Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group, a private military company with combat experience in Ukraine, Syria and Libya - though both governments deny this.

CAR's rebel groups - including Return, Reclamation, Rehabilitation (3R) - are largely drawn from the country's Muslim minority, which has long faced marginalisation.

Ahead of presidential elections last December, 3R joined a loose rebel alliance, causing the collapse of peace agreements signed in 2019.

With Russian help, the armed forces have since driven them back, retaking towns and villages which have languished beyond state control for years.

But according to a recent UN report, external, they have committed almost as many documented abuses as the rebels over the past year, ranging from abductions and arbitrary detentions to rape, torture and summary killings.

Black-market landmines

Compounding this violence is the emerging threat of landmines and IEDs, which are increasingly prevalent in the region, particularly in northern Nigeria, the Lake Chad basin and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The first known use of them in CAR came in June 2020 during a UN-backed offensive against 3R, which began using these weapons in a brutal attempt to cling on to territory.

Muslims in the CAR have long demanded more representation in CAR

Among the devices being laid was a type of anti-tank mine known as a PRB-M3, a powerful, Belgium-made explosive from the 1970s and 1980s.

Weapons experts say these mines are probably being trafficked from Libyan stockpiles or harvested from active minefields in Chad and Sudan before entering the black market.

David Lochhead, a senior researcher with the Small Arms Survey, says CAR's rebels appear to be copying jihadist groups in Mali who have incorporated this type of mine into IEDs alongside other homemade explosives to create bigger blasts that destroy armoured vehicles.

"It's a very worrying trend," he said. "An IED may cost $35 (£26) to build and you can defeat an armoured vehicle that costs $500,000."

After the UN force ended its brief assault on 3R's strongholds, mine-related incidents all but stopped until the government's bid to rout rebels from provincial towns began this year.

In total, between January and August, explosive ordnance killed at least 14 civilians, including a pregnant woman and two children, injured a further 21 as well as two peacekeepers in more than two dozen incidents, according to the UN's humanitarian agency Ocha.

"Access here has been extremely complex - you have shifting conflict lines, poor infrastructure, now the rainy season. But explosive ordinance is a new ballgame," Ocha's Rosaria Bruno said.

3R rebels are based in the north-west of CAR

The impact on civilians is calamitous. Planted on roads and even near schools, the landmines and IEDs cut villagers off from peacekeeper patrols and humanitarian help, and force people from their homes. More than 1.4 million people are currently displaced nationwide - the highest level for five years.

For example, around 1,000 people fled their village in the Nana-Mambéré region after a device exploded there in May; the village remains inaccessible because of the continuing lethal threat.

Some aid has been airlifted in by helicopter, including 1.5 tonnes of medicine, hygiene products and food for the villagers. But such operations are costly and unsustainable in a humanitarian emergency to which the response plan faces a funding gap of almost $190m, external - more than 40% of the required amount.

Smear campaigns

The impact is felt too by the UN's 15,000-strong peacekeeping force (Minusca), which has been hit by numerous sexual abuse allegations.

The beleaguered force has also been the target of smear campaigns from all sides, while its mission has been obstructed by the presence of explosives and also by Russian personnel deployed in the field.

Last month it faced rumours that it was supplying rebels with landmines, even as it was deploying personnel to remove these devices.

The UN has experts in the CAR to deal with unexploded weapons

"Minusca has never used mines," said UN forces spokesman Maj Ibrahim Atikou Amadou, adding that de-mining operations were still at an impasse because of the accusations.

Though it seems responsibility for laying landmines may not lie solely with the rebels.

A UN report in June, external revealed that government troops had warned local communities in two different parts of the country that Russian soldiers had placed mines on a road and near a bridge.

Other sources said this was not the case but that such rumours had been circulated in a bid to deter rebels from launching attacks.

Regardless of whether the bomb presence is genuine, the fear created is real, limiting farming and preventing children going to school, the UN report said.

Pupils in some areas are unable to go to school because of the threat of landmines

Both CAR and Russia deny that their forces have committed human-rights abuses or used landmines or other explosive devices.

While 3R has been widely blamed for planting mines, the group denies this, blaming the Russians.

More than 20 years ago, a global treaty banned the use of landmines targeted at individuals, though Russia is not a signatory and mines intended to destroy vehicles fall outside the convention.

'No military solution'

Experts warn that, despite their breath-taking advance, government forces have not eliminated the rebels, simply pushing them to peripheral areas and forcing them to adopt guerrilla tactics.

Neither have they addressed the underlying grievances that fuelled their appearance in the first place - the state's long-term and violent discrimination against the Muslim population.

"It is clear that there isn't a military solution to this conflict," said Ms Caldera.

"While the security forces are making progress in recapturing territory, they are wreaking havoc on the civilian population and not restoring stability whatsoever."

This week, CAR President Faustin-Archange Touadéra shrugged off criticism of his alliance with Russia, and insisted he was open to dialogue with the rebels, saying, external: "I did not choose this war."

As the country slips deeper into disaster, civilians bearing the brunt of the clashes will be hoping he pursues another course.

Jack Losh is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker focusing on conflict, conservation, humanitarian issues and the crisis in CAR

More about the conflict in CAR:

Why is Russia helping the Central African Republic?

Related topics

- Published22 August 2023