Why Kenyan churches are banning politicians from pulpits

- Published

Kenya's churchgoers have been used to smartly dressed politicians rolling up in flash cars to attend services on Sundays - often with cameras in tow.

They tend to arrive flush with cash donations - carried by their handlers in shoulder bags - which can be used for the construction of mega churches and the purchase of loud music systems.

In exchange for this largesse, midway through the service, the politician takes to the pulpit, where the congregation becomes a captive audience for their message, which often has little to do with the bible.

These "sermons" often make it to TV bulletins to satisfy an insatiable appetite for news about those manoeuvring ahead of the next election, still nine months away.

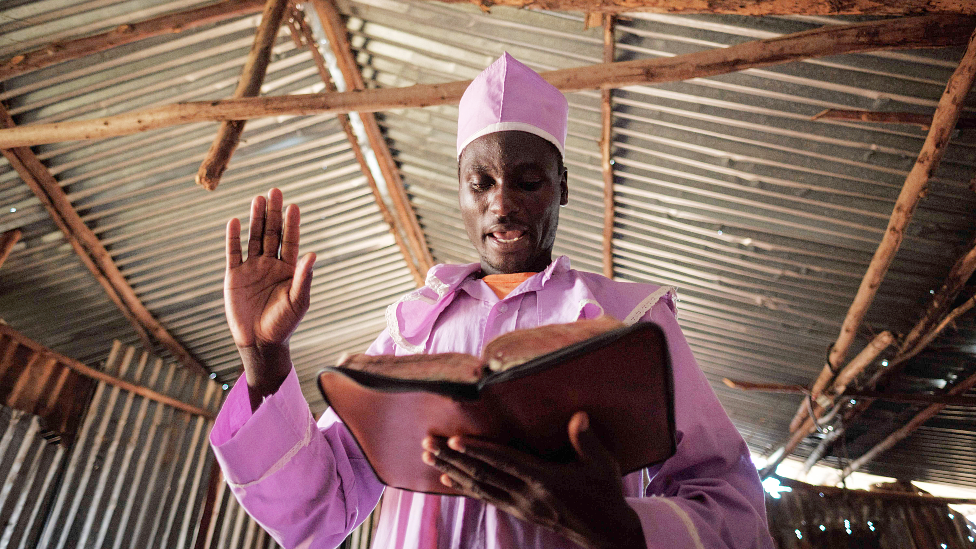

Established churches want the pulpit to be reserved for religious sermons

Some tour around in search of new congregations, leading to some clashes inside churches with politicians accusing each other of invading one another's turf.

Priests have also been known to be invited to politicians' homes to discuss "development affairs" - as part of negotiations to ease these turf wars.

There are allegations - denied of course - that some of the donations are the proceeds of ill-gotten gains.

Now leaders of the established churches have had enough. They have banned politicians from the pulpit, accusing them of making "divisive and unedifying" remarks that "desecrate the church".

President Uhuru Kenyatta (centre-left) and his deputy William Ruto (right) regularly made joint church appearances before they fell out

In order to reduce media attention, the churches will also no longer disclose the amounts donated by politicians towards church projects.

"Partly priests are to blame for the capture of the church by politicians. There was need to return the practice into its purity," Catholic Archbishop Anthony Muheria explained to the BBC.

The head of the Anglican Church in Kenya, Archbishop Jackson Ole Sapit, concurred that it was a "mistake" to give leeway to politicians in churches in the first place.

"I own it 100%. But we can't remain in the same mistake for long. A moment of repentance - a turnaround - is needed," he said when the ban was announced last month.

'Politicians are selfish people'

The move has been welcomed by some - especially these churchgoers I spoke to in the capital, Nairobi.

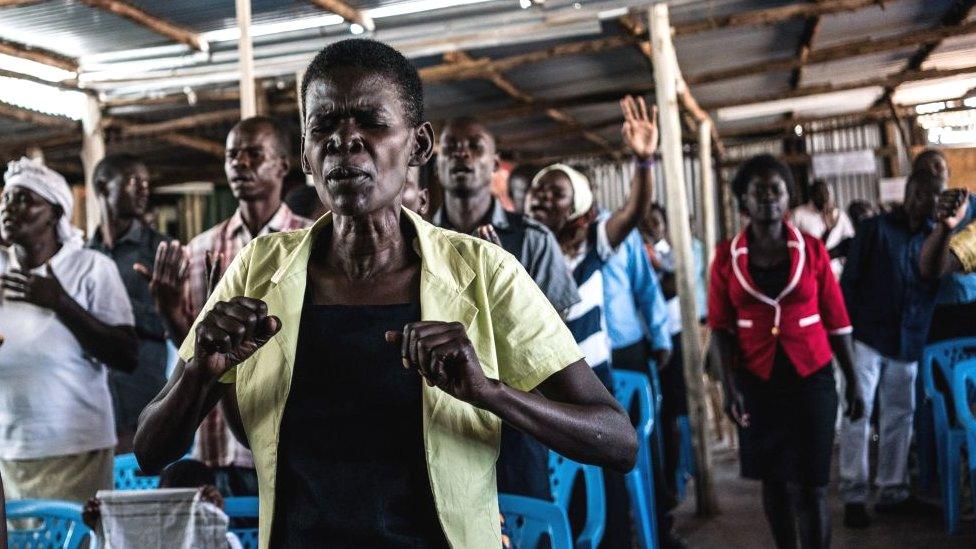

Most Kenyans now worship at evangelical churches

"To be honest it was a distraction. I have been waiting for church leaders to deal with it," said Eunice Waweru.

Janet Nzilani agreed: "I'm glad the decision was made because politicians are selfish people. They are not there to inspire people or to call for unity. They don't value people at all. Pastors should just recognise their presence [in church] and nothing else."

Florence Atieno said that politicians should be treated with respect, acknowledged by a pastor if they were in the congregation and be allowed to greet congregants after a service.

"My only problem is when they start campaigning and abusing each other in church," she said.

But these women all attend evangelical churches whose clerics may not necessarily agree with the pulpit ban.

It is being led by the Anglican, Catholic and Presbyterian churches and is facing resistance from those ministries where allegiance to self-proclaimed prophets and faith healers is huge.

Big business

Kenyans are predominantly Christian - 85.5% of the country's 50 million people, according to the 2019 census, external - with most now going to evangelical churches. The Catholic Church is the next most popular denomination.

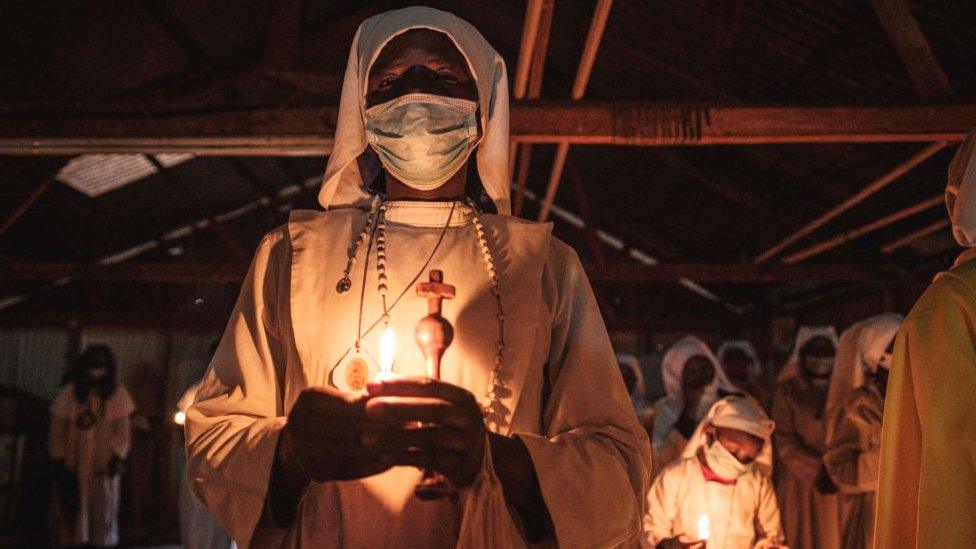

The pandemic has made it difficult for churches to raise money as congregations were banned for more than a year

The faith economy is big business - and a fundraiser with the right politician can greatly improve the fortunes of a church.

Many churches have been left cash-strapped as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, so it is no surprise that some evangelical clerics have opposed a blanket pulpit ban.

"I don't think it will take root because we have churches that are opportunistic, they are looking for politicians who will give them money, sometimes they even invite them themselves," media commentator Barrack Muluka told the BBC.

Author and scholar Peter Kimani explains that the clergy of the established churches no longer have the control they did in the 1990s.

"It is no longer a unifying force… The evangelicals are briefcase operations and have no organising principles," he told the BBC.

Religious studies scholar Josephine Gitome notes that many worshippers may not be that bothered by the politicians' behaviour.

Most Kenyans may be churchgoers, but are not that religious day-to-day: "There is concern about whether their behaviour between Monday and Saturday concurs with their behaviour on Sunday."

Moral 'failures'

The pulpit ban seems to signal that mainstream churches want to regain some moral authority.

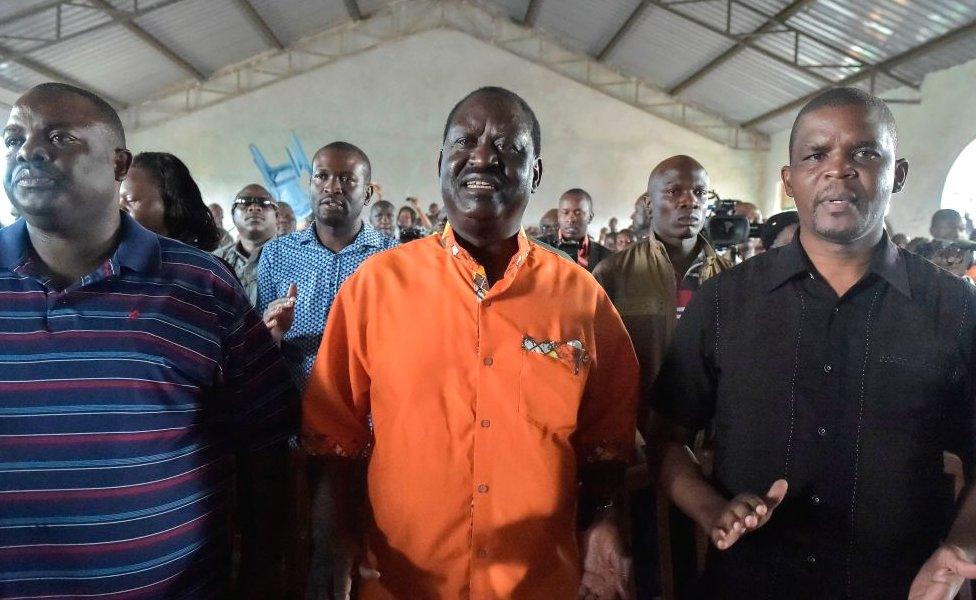

Kenyan opposition leader Raila Odinga (centre) seen in church in October 2017 before getting up to address the congregation

Previously church leaders had clout when speaking out on public affairs and over human rights issues - they pushed for a return to multiparty democracy in the 1990s.

But public confidence has dwindled over controversial positions taken over the last two decades.

Opposition lawmaker Otiende Amollo believes the churches missed the mark on three major occasions:

By failing to speak out strongly enough at the height of the post-election violence between 2007 and 2008

By opposing the new constitution, introduced after a referendum in 2010 to ease ethnic tensions

And by failing to mediate between political factions after the Supreme Court nullified the August 2017 presidential election results.

"These events significantly reduced the standing of the church and it will take quite some time for it to regain that standing," Mr Amollo, who was among the lawyers who convinced judges to cancel the first 2017 poll results, told the BBC.

Pandemic restrictions were partially lifted for church congregations in June - though campaign rallies remained banned, meaning churches became inundated with politicians.

President Uhuru Kenyatta, a practising Catholic, has recently further eased restrictions allowing churches up to two-thirds of their capacity, though rallies are still prohibited.

So the pulpit ban does not sit well with campaigning politicians, like Deputy President William Ruto, who is eyeing the presidency.

"We come as Christians to support church projects," he was quoted as saying at an evangelical service in central Kenya, external where he reportedly donated two million Kenyan shillings ($18,000; £13,000).

Mr Amollo thinks the churches should go further and ban politicians from fundraising events too.

But church leaders are at pains to say Bible-wielding politicians themselves are not banned.

"Politicians are still welcome to pray but without any preferential treatment to address congregants," Ferdinand Lugonzo, head of the secretariat of the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops, told the BBC.

"The church building is consecrated for purposes of worship only."

More on Kenyan religion and politics:

Meet the Kenyan priest rapping about religion