Viewpoint: Why Ethiopia's Tigray region is starving, but no famine declared

- Published

Despite mass starvation occurring in Ethiopia's northern region of Tigray, senior international aid officials are tiptoeing around declaring a famine nearly a year after the civil war erupted.

Warning: Some people may find a photo in this story upsetting.

A report from Ayder Referral hospital in Tigray's capital city, Mekelle, this week described children dying of starvation.

The doctors provided photographs of small children suffering from acute malnutrition, their ribs and swollen bellies evidence of their plight. Those are the lucky ones as there is still a few weeks' supply of emergency therapeutic food at the hospital.

In Tigray's villages, the situation is grave. The war started last November and just two months later, the Catholic bishop of Adigrat described people perishing of hunger, external.

In June, one village committee compiled a list of 125 people who had starved to death in their isolated community, external.

Families who arrive in Mekelle after trekking for days on foot describe trying to survive on a diet of leaves and roots for weeks.

This is one of the malnourished children being treated at Ayder Hospital this week

The director of Ayder Hospital, Dr Hayelom Kebede, tells how his nurses arrive at work with only a small bag of roasted grain to eat for the whole day. Their own children are malnourished. Because banks have been closed since June, staff have gone four months without salaries. Even as cash dries up, the prices of essentials shoots up.

More than 20% of displaced children were acutely malnourished in August. A recent survey reported by the UN indicated 79% of pregnant and nursing mothers were in the same state. These are levels rarely seen in modern times, comparable to the 2011 Somali famine that claimed more than 250,000 lives.

'Famine-like conditions'

In the months after the war broke out, the data and maps provided by the UN Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Ocha) show a steadily deteriorating humanitarian crisis, culminating in the estimate of 400,000 people being in phase five of the UN-backed Integrated food security Phase Classification (IPC) system. Phase five is "catastrophe" or, when certain criteria for the threshold of populations in specific areas are met, "famine".

This is the basis of the oft-repeated statement that 400,000 people are in "famine-like conditions". Meanwhile the great majority of Tigray's six million people are in need of emergency aid.

In June, the UN activated the Famine Review Committee (FRC), an independent group of food security experts, to assess the available evidence from Tigray. Its report made projections for what would unfold over the coming months, external, with four possible scenarios depending on the scale of fighting and the level of humanitarian aid.

Its worst-case scenario has come to pass: the war has escalated and there is only a trickle of humanitarian aid - less than 10% of needs - along with a near-complete shutdown in the economy with banks closed and essential supplies blocked. The committee assessed the risk of full-scale famine on this scenario as "medium to high" before the end of September and "high" after that.

In its dry, technical language, the FRC report was a call for emergency action - not only a massive humanitarian aid effort but also intensified information gathering so that the agencies know what to supply, where and to whom.

Indeed the FRC devotes whole pages of recommendations to data gathering and analysis, including weekly monitoring, regular analysis updates, and another full assessment within three months.

None of this has happened. In fact, the few international aid workers permitted to travel to Tigray are not allowed to take secure communications equipment or even USB drives, and their smartphones are searched for pictures on their return.

In previous Ethiopian famines, it was journalists who broke the news. Jonathan Dimbleby reported on the "unknown famine" in 1973. A BBC crew with Michael Buerk and Mohamed Amin revealed the 1984 famine, which the then-military government was trying to conceal. Today's government has kept all journalists out of Tigray.

Aid convoy row

In June, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed told the BBC: "There is no hunger in Tigray." Reflecting the sensibilities of the government, the official language of the UN is that famine may be "in prospect soon" and that people may "start to die" for lack of food.

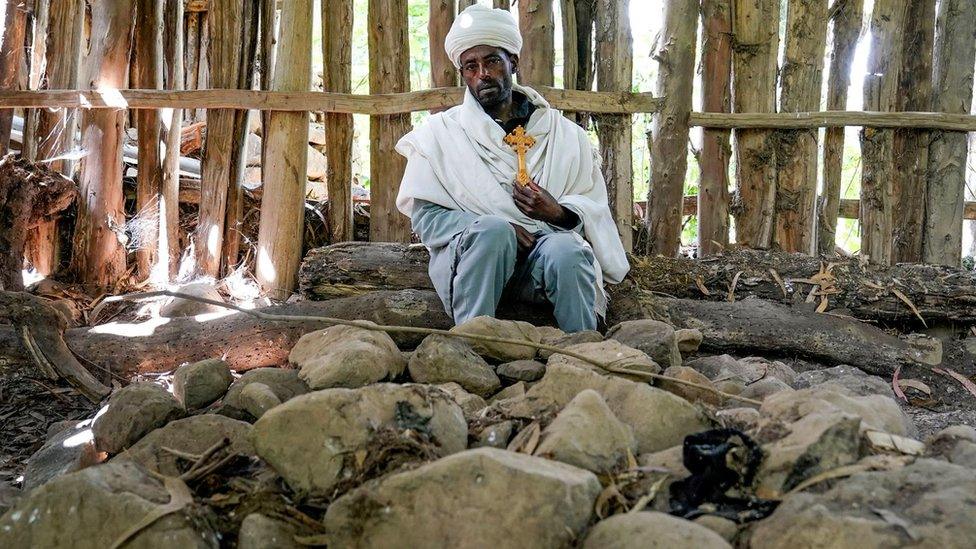

Priest Tiftu Ejigu says his wife and daughter were killed by Tigrayan fighters at a church in the Amhara region, charges the rebels deny

The Ethiopian government says that responsibility for the crisis lies with the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), the ruling party of the region which it has declared a terrorist organisation.

It accuses Tigrayan fighters of advancing into the neighbouring regions of Amhara and Afar and creating humanitarian crises there. Indeed, the UN reports that about a million people in those regions need emergency aid, half of them displaced by fighting - though BBC fact-checkers have found that images on social media purporting to show starvation there are in fact from other places and other times.

There are also reliable reports that the advancing Tigrayan forces have requisitioned food and medicine supplies.

The government also says that the Tigrayan advances have blocked humanitarian access routes. However, there hasn't been any fighting on the main road used by aid convoys from the Afar city of Semera, while aid agencies attribute insecurity to government-aligned militia.

It also says that the reason why so few trucks are able to travel to Tigray is that those who arrive are commandeered by the TPLF for its war effort. Fact-checking by the BBC shows this is not supported by evidence - the aid trucks are stranded in Tigray because fuel supplies have run out.

The government blames the food crisis on a locust infestation last year and points out that a million people needed aid before the war began.

In fact, it was the TPLF's defeat of the Ethiopian army in Tigray in June that made it possible for farmers there to plant crops and aid agencies to travel unobstructed within the region.

The problems of humanitarian access are not within Tigray - but getting there in the first place.

UN officials are increasingly explicit that it is the government policy of blockading the region that is the root of the problem.

On 29 September, Ocha head Martin Griffiths said: "This is man-made; this can be remedied by the act of government." Two days later, the Ethiopian government expelled seven senior UN officials, accusing them of "meddling" in the country's internal affairs.

In an open session of the UN Security Council, UN chief António Guterres condemned the expulsions and explained that they violated the terms of the UN's agreement with Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian representative to the UN, Taye Atske Selassie, then made a series of allegations that UN staff were TPLF sympathisers and, in a step almost without precedent, Mr Guterres took to the floor a second time to challenge him to provide evidence, saying that he had personally spoken twice with Mr Abiy on the topic, without the prime minister providing details to back up the allegations.

Mr Griffiths' predecessor at Ocha, Mark Lowcock, has been more candid since his retirement in June. Last week he was asked by PBS Newshour, external, "Is the Ethiopian government trying to starve Tigray?" He answered simply: "Yes."

Mr Lowcock continued: "There's not just an attempt to starve six million people but an attempt to cover up what's going on."

There is no question that Tigrayans are starving. But because there are no nutrition and mortality surveys of the type that are standard in such emergencies, the UN is hesitating to call it a famine. That is a technical nicety that is increasingly difficult to defend.

Speaking at the G7 summit in June, US special envoy Jeff Feltman warned, we "should not wait to count the graves" before declaring the crisis in Tigray what it is: a famine. That was a warning. Without immediate action it will be a forecast, and a verdict.

The question is no longer whether there is famine in Tigray, but how many people will starve to death before it is stopped.

Alex de Waal is the executive director of the World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in the US.