After Desmond Tutu, a time for new South African heroes

- Published

The last of South Africa's moral giants is being laid to rest after a week of national mourning

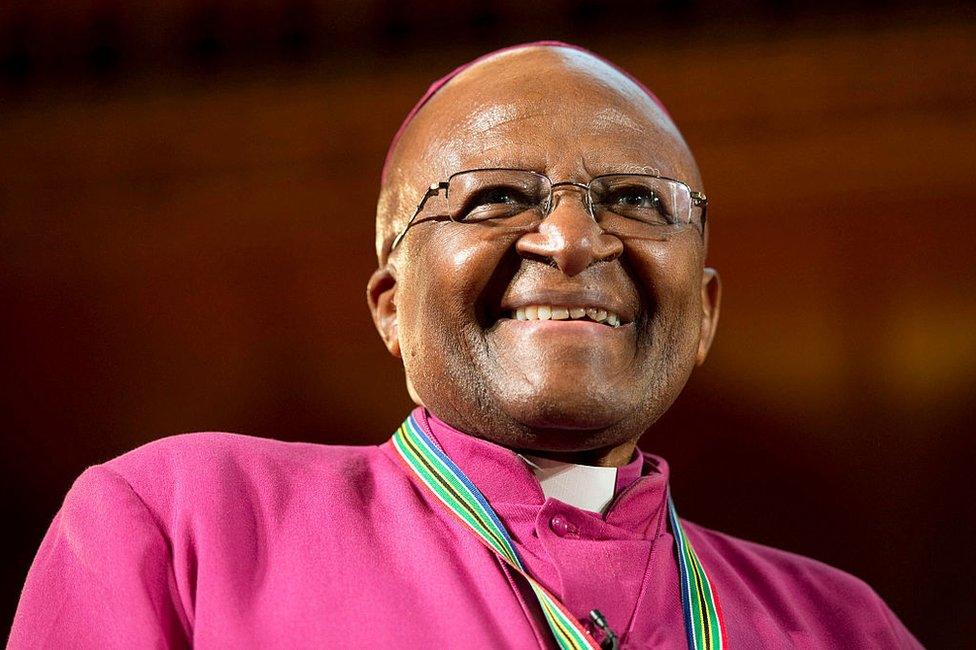

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was the last truly global figure from an era when South Africa taught the world what courage and reconciliation could achieve.

The last of an extraordinary generation of moral giants - of men and women who, in the 1980s and 1990s, steered a turbulent, traumatised country away from cruelties of racial apartheid and the cliff-edge of civil war.

With Desmond Tutu gone, South Africa finds itself not quite rudderless or leaderless, but fully untethered, at last, from the years of its greatness.

The contrast between those times of sacrifice and glory, and today's far shabbier political realities can certainly appear stark.

The country Tutu finally leaves behind is a troubled one, gripped by deep economic malaise, by chokingly high unemployment and enduring inequality, and governed by a former liberation party, the African National Congress (ANC), which is at open war with itself.

Tutu was too frail to comment on the political violence that erupted in July this year - as supporters of the disgraced former President Jacob Zuma responded to his imprisonment for contempt of court by orchestrating an attempted insurrection.

But the Archbishop had, for years, made clear his growing disillusionment with the ANC and its slide into factionalism and corruption. Those close to him spoke of his deepening concern that so many of the hard-won achievements of liberation were being squandered.

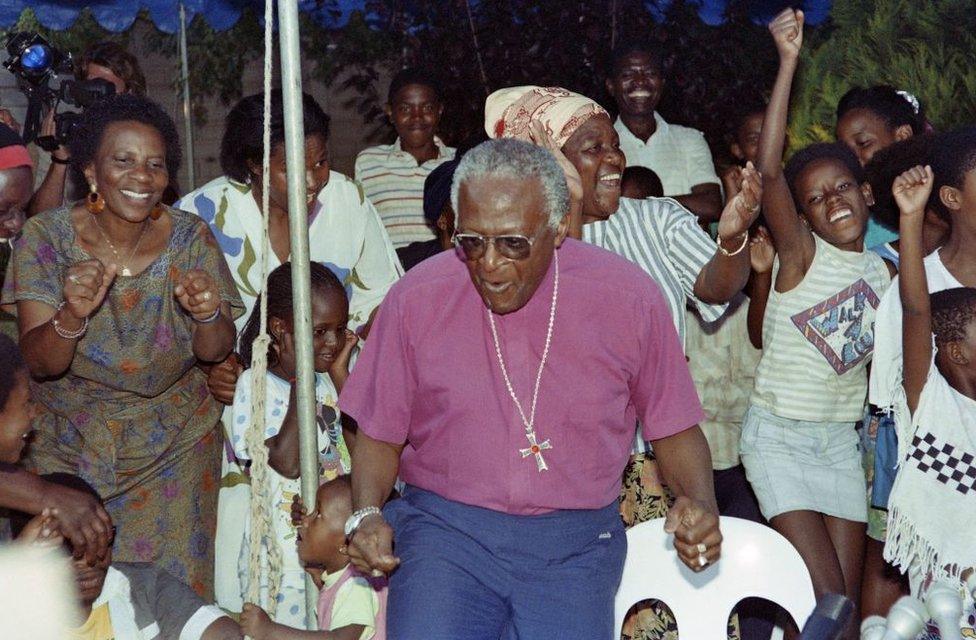

Archbishop Desmond Tutu jubilating as fellow anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela is freed from prison in 1990

Disappointment is, perhaps inevitably, the price one pays for longevity.

Not surprisingly, some prominent figures in the ANC have chosen to stay silent in recent days, rather than joining those offering sometimes hypocritical tributes to a man who spent so much time berating them as "worse than the apartheid government" - a man some of them chose to ignore or insult, or simply told to "shut up".

But this week, others have chosen to hit back and to attack Tutu - on social media, in particular, of course - as some sort of "sell-out," as a man who prioritised reconciliation over justice, the sensibilities of white people over the needs of the black majority. The accusation is not new. But it is worth noting.

For years, some politicians here have sought to exploit the frustrations of impoverished South Africans - those who have gained the least from democracy and years of economic stagnation - by accusing Tutu and also Nelson Mandela of being too quick to compromise with apartheid's leaders and business magnates.

They accuse the two men of enabling white South Africans to keep hold of their ill-gotten wealth, and apartheid's death squads to enjoy comfortable retirements.

In short, they have accused Tutu of over-selling the idea of a "rainbow nation" - the phrase he coined and championed.

Desmond Tutu's detractors accused him over-selling the idea of a "rainbow nation"

The allegation is widely contested and debated here in South Africa.

But it touches on something very specific to both Tutu and Mandela as leaders - on their astonishing capacity, vital in those tense and desperate years before and during the fall of apartheid, to bring people together and to achieve international appeal. Mandela depended on a certain easy grandeur, sprinkled with wit.

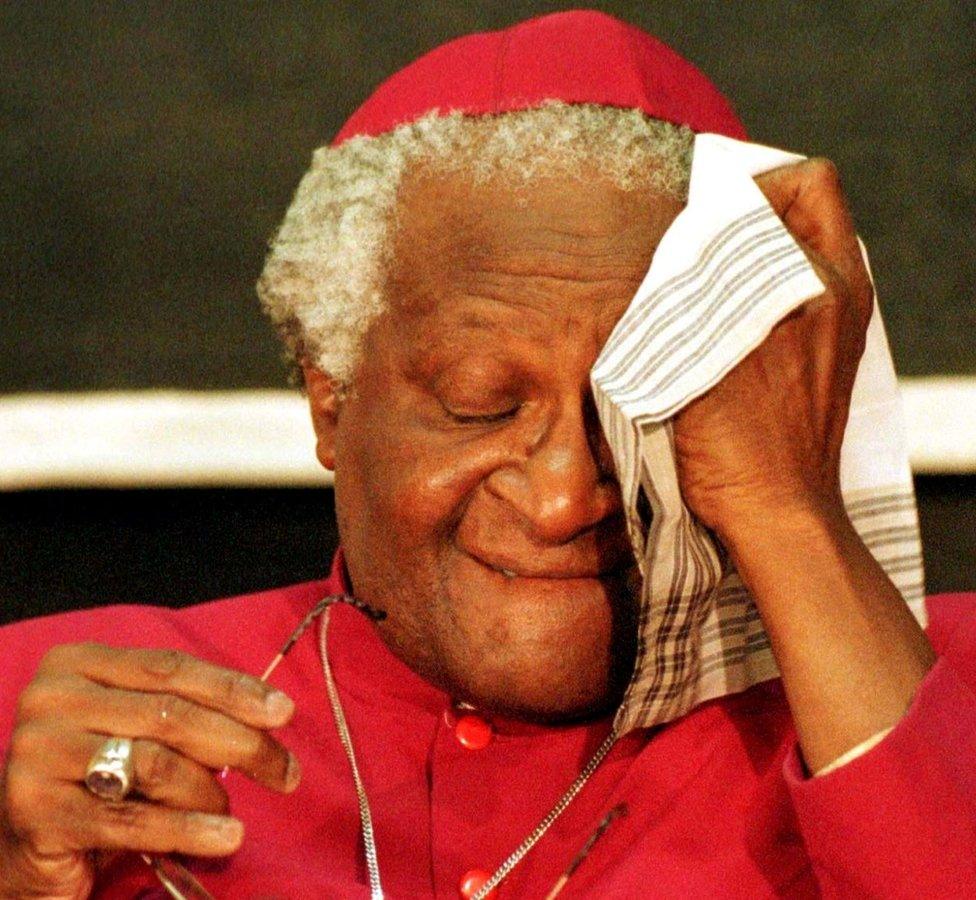

Tutu's appeal relied on a more raucous form of humour, balanced by his readiness to show vulnerability and deep emotion.

He would mock apartheid's leaders, urging them to join "the winning side, before it's too late," and drawing laughter from angry crowds in South Africa's embattled black townships. And Tutu would cry publicly, in the mid-1990s, at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which he led, channelling the grief and trauma of millions of people who watched on television as the daily revelations of torture and abuse suffered at the hands of apartheid security forces emerged.

Tutu was often moved by the disturbing testimony at the landmark Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The TRC was imperfect - and contested by many in the ANC, including Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, who was found to have committed terrible crimes and felt she was unfairly equated with her oppressors as a result. But it was part of a healing process considered vital at the time and would have been impossible without Tutu's presence.

Put simply, what Tutu and Mandela had, in abundance, was charm. And, channelled in different ways, that charm was vital to South Africa's journey and to its successes. As were the compromises made during the tortuous negotiations that enabled the country to avoid a racial civil war.

Those now seeking to rewrite history, free of context, and to chip away at Tutu's legacy are in a minority.

But it is also true that, particularly in their later years, both Tutu and Mandela - so affable, so inclusive - became international mascots for tolerance and forgiveness.

And it is easy to understand why some South Africans might feel uncomfortable, even resentful, about the way these men - fierce and uncompromising struggle heroes - have been repackaged as "cuddly" advocates of "rainbow-ism," to be wheeled out, shorn of their righteous anger, for the delight of Western audiences, rock stars and royalty.

The truth, of course, is that Tutu was many different things to many people. In death he is claimed, and contested, just like Mandela. That is the nature of an icon.

But what of Tutu's legacy in today's South Africa, a whole generation after he helped steer the country to democracy?

So much time has passed since those heady days. Is it even meaningful to ponder what it means for a nation to be cut adrift from the great moral leaders of the past?

Archbishop Desmond Tutu was unsparing in his criticism of the governments of ex-President Jacob Zuma (C) and Thabo Mbeki before him

Like Mandela, Tutu will never be forgotten. He will continue to live on as an example and inspiration to countless others. Surely, that is enough.

And it may be a difficult thing to say, or argue, at a time when so many are mourning his death, and celebrating his joyful, prayerful, extraordinary life, but it may be no bad thing that South Africa is finally closing not just another chapter in its struggle history, but the whole book.

Why? Because it may be time, as the political commentator Eusebius McKaiser put it to me, for South Africa to find "a different kind of hero - a more boring kind of hero".

In a modern era of political tensions and economic gloom, the nation needs someone who can shift the focus away from its contested past and instead inspire people to focus on - and to find solutions to - today's duller, technocratic challenges.

Above all, there is the urgent task of building and reshaping an economy so that it can lift millions out of poverty and make Tutu's rainbow nation the reality he always insisted it could be.

More about Archbishop Desmond Tutu:

IN PICTURES: The life of Archbishop Tutu

OBITUARY: South Africa's rebellious priest

Watch: The BBC's Nomsa Maseko looks back at the life and legacy of Desmond Tutu