Rwanda genocide: 'I forgave my husband's killer - our children married'

- Published

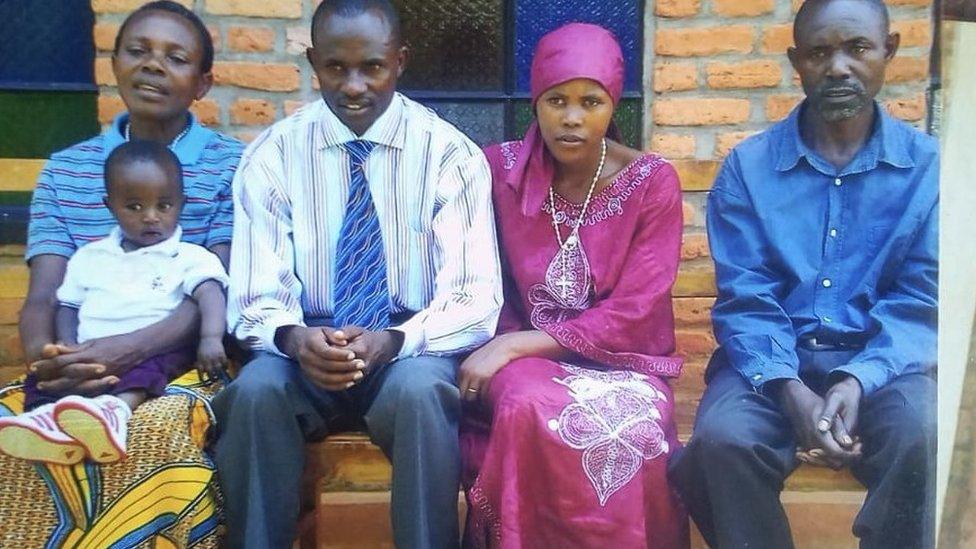

Alfred and Yankurije married 14 years after the genocide

To heal you must love - so believes a woman who not only forgave the man who killed her husband 28 years ago during Rwanda's genocide, but allowed his daughter to marry her son.

Bernadette Mukakabera has been telling her story as part of continuing efforts by the Catholic Church to bring reconciliation to a society torn apart in 1994 when some 800,000 people were slaughtered in 100 days.

"Our children had nothing to do with what happened. They just fell in love and nothing should stop people from loving each other," Bernadette told the BBC.

She and her husband Kabera Vedaste were from the Tutsi community, who were targeted after an aeroplane carrying Rwanda's ethnic Hutu president was shot down on 6 April 1994.

Within hours, thousands of Hutus, indoctrinated by decades of hateful propaganda, began well organised killings - turning on their Tutsi neighbours around the country.

One of these was Gratien Nyaminani, whose family lived next to Bernadette's in Mushaka in western Rwanda. They were both farmers.

After the massacres ended, with a Tutsi rebel group taking power, hundreds of thousands of people accused of involvement in the killings were detained.

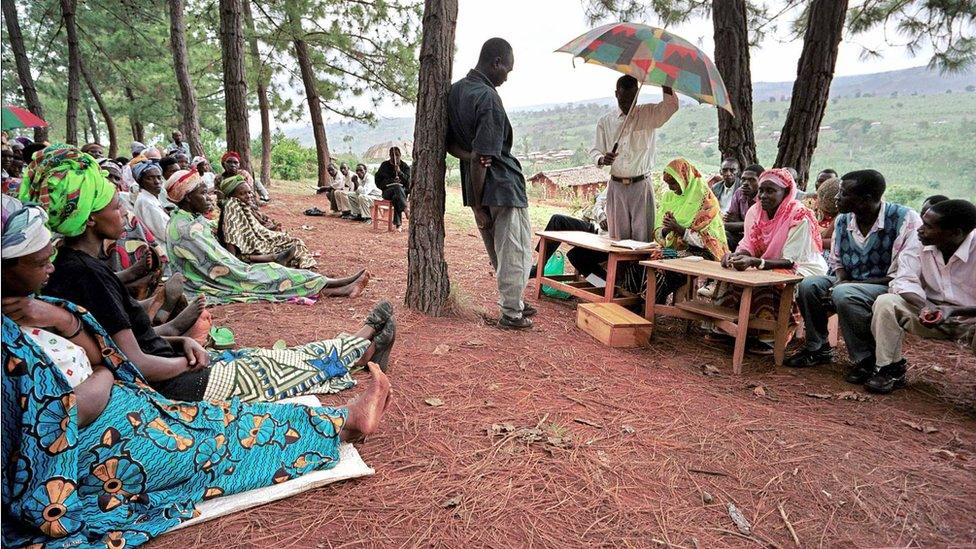

Gratien was taken into custody and eventually tried by one of the community courts, known as gacaca, set up to deal with genocide suspects.

At these weekly hearings, communities were given a chance to face the accused and both hear and give evidence about what really happened - and how it happened.

Rwanda's traditional gacaca courts dealt with hundreds of thousands of genocide suspects

In 2004, Gratien told Bernadette how he had killed her husband and apologised - and at the same hearing she chose to forgive him.

This meant that he did not have to serve a 19-year jail term, but a two-year community service sentence instead.

'I wanted to help'

During the 10 years he was in detention before his public apology, his family had sought to make amends with Bernadette and her son Alfred, who was about 14 years old when his dad was killed.

Bernadette (R) and daughter-in-law Yankurije (L) have a close bond - and their families remain united by love

Gratien's daughter Yankurije Donata, who was about nine at the time of the genocide, began to go over to Bernadette's and help around the house.

"I decided to go and help Alfred's mother do the housework and even the farm because she had no-one else to help her considering that my father was responsible for her husband's murder," she told the BBC.

"I think Alfred fell in love with me when I was helping out his mother."

Bernadette was touched by her consideration: "She helped me knowing well that her father killed my husband, she knew that I didn't have any help because my son was at boarding school.

"I loved her heart and behaviour - this is why I didn't resist her becoming my son's wife."

But for Gratien it was not so simple - he was at first sceptical when told of the marriage proposal.

"He kept asking how and why a family he offended so much would want anything to do with his daughter," Yankurije said.

The happy couple flanked by Bernadette (L), holding their son, and Gratien (R)

At last he was persuaded and gave his blessings as Bernadette was adamant that she harboured no ill-will towards Yankurije.

"I did not have any resentment towards my daughter-in-law for her father's actions," Bernadette says.

"I felt like she could make the best daughter-in-law because she understood me better than anyone else. I persuaded my son to marry her."

The couple wed at the local Catholic Church in 2008.

This is where Gratien had confessed before the congregation after completing his community service two years earlier - seeking forgiveness.

'No reconciliation, no holy communion'

The church has been at the centre of efforts to reunite communities in the area.

Father Ngoboka Theogene from the Cyangugu Diocese says people have embraced its reconciliation programme. Several other denominations have facilitated similar initiatives.

The churches realise that people have no choice but to live together, so much better do so in peace and understanding.

"Those accused of genocide crimes are not allowed to partake of the sacrament until they have reconciled with their victims' family," Father Ngoboka explains.

The final reconciliation happens in public where the accused and the victim stand together.

"The victim stretches their hands towards the accused as a sign of forgiveness," he says.

People attended a recent event in Mushaka to mark 28 years since the genocide to learn ways to coexist, not long after Gratien had died.

"When we speak about change it is not about changing one's skin colour but changing your bad character," said the event's facilitator, Apiane Nangwahabo from the Mushaka parish.

"A change of heart is important before deciding to live a holy life."

It was here that Bernadette spoke about her son's marriage to the daughter of her husband's killer.

"I love my daughter-in-law so much and I don't know how I would have survived if she wasn't here to help me after my husband died."

She says she is heartened to see that Alfred and Yankurije's love story has encouraged many others to seek and offer forgiveness.