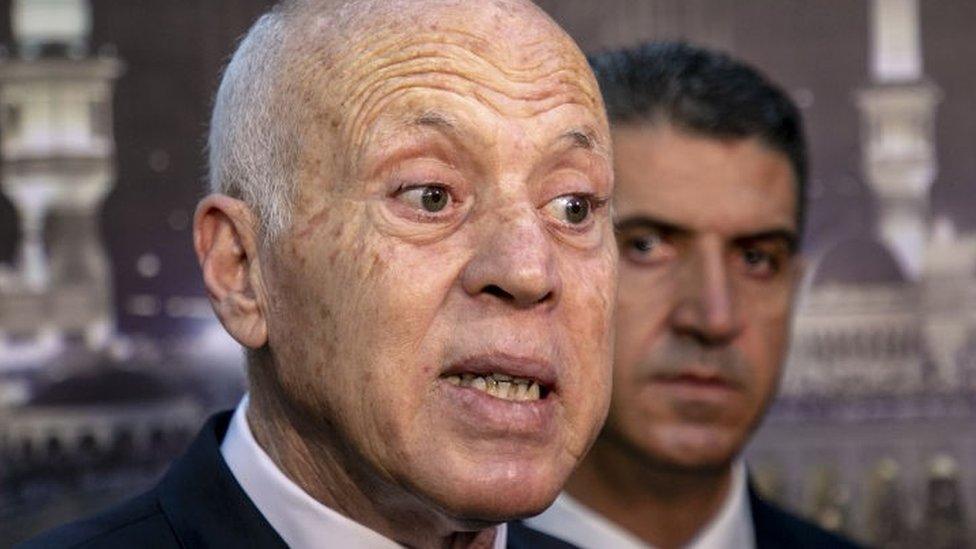

Tunisia referendum: President Kais Saied seeks mandate to extend powers

- Published

As Tunisia's president asks voters to approve on Monday a new constitution that gives him greater powers, North Africa analyst Magdi Abdelhadi looks at the man seen by his supporters as a saviour and by his opponents as a usurper of power.

President Kais Saied clearly feels that he is a man of destiny. Although his authoritarian streak is neither unique nor new to Tunisia or the region, his academic credentials and rhetorical style separate him by a long distance from all other Arab autocrats.

Delivering his speeches in impeccable classical Arabic, often adlibbed, at a considered pace, the former law professor conveys a sense of a man who weighs his words carefully, with clear focus and vision and ironclad determination.

Despite mounting criticism both at home and abroad since he assumed total power in Tunisia a year ago, he has continued undeterred to his, and his alone, desired destination. This may very well be part of his appeal to many Tunisians.

Tunisia was the birthplace of the Arab Spring, which saw the overthrow of long-serving ruler Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011.

But after more than a decade of political instability, which saw 10 governments come and go and endless squabbles in parliament, at times degenerating into violence, many Tunisians have simply grown sick of this "democracy", which brought no tangible improvement to their quality of life.

On the contrary, the economy was in free fall, with all economic indicators pointing in the wrong direction: inflation and unemployment up, foreign debt up, and the value of the Tunisian dinar has plunged.

And things got much worse as the Covid pandemic struck, and even more so after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the impact it had on food and energy prices.

With inflation soaring, many people are struggling financially

Mr Saied is not against the Tunisian revolution, at least that is what he says in public. Rather, he sees himself as the man of the people, who "corrects" the path of the revolution.

But the word "correction" - tassheeh in Arabic - has a notorious history in Arab politics. It has often been deployed to justify power-grabs.

Characteristically, the leader of "the correction" is motivated by selflessness and a profound sense of the weight of history upon his shoulders. He wants to set history right.

Mr Saied's constitution enshrines that narrative.

Speaking in the name of the Tunisian people, who have not been consulted in any significant way in its drafting, the draft constitution says: "Out of a sense of profound historic responsibility to correct the path of the [2011] revolution and the path of history itself, that is what happened on July 25 2021."

That is the day President Saied sacked the government, suspended the parliament and embarked on his single-handed mission to redesign the country's political future.

Critics say he's taking Tunisia back to where it was before the 2011 Arab spring - outright autocracy.

We will soon find out whether the Tunisians will endorse that narrative and back Mr Saied's authoritarianism.

In fact, Tunisians are not alone in expressing disappointment with democracy. Disillusionment with the ability of a democratic system of government to tackle economic hardships is part of a wider trend of perceptions in North Africa and the Middle East.

According to a recent survey, 81% of Tunisians prefer a strong leader, and 77% are more interested in effective government than the form it takes.

Tunisia's political crisis has been worsened by the economic crisis

There is a broad consensus among most observers that the new constitution reverses many of the democratic gains of the 2014 constitution that has been de facto annulled by Mr Saied. He has ruled by decrees since July last year.

As has been widely anticipated, Mr Saied's constitution is designed to give greater powers to the president and far less of it to the elected parliament.

This is a reversal of the balance of power between the two institutions as it was established in the 2014 constitution.

Crucially, it sets no curbs on presidential powers. There is no way of impeaching him in parliament or by any other institution.

Further, it is the president who selects the prime minister and the ministers, and he can dismiss them. He can also dissolve parliament as it seeks to withdraw confidence from the government.

The new constitution also undermines the independence of the judiciary - a cornerstone of a democratic system.

The mass dismissal of judges by the president has caused outrage in Tunisia

In short, it takes Tunisia back to the presidential system it had since independence with an emasculated parliament that has limited oversight powers.

But the draft does introduce some real innovation - not just for Tunisia, but for the entire region.

It removes the clause, found in most constitutions in the Arab world, that stipulates that Islam is the religion of the state and puts the relationship between religion and the state on a new trajectory.

Instead, the document says that "Tunisia is part of the Islamic nation, and only the state has to work to achieve the objectives of Islam". These are defined as protecting the individual's life, integrity, wealth, religion and freedom - no reference here to Sharia (Islamic law), which has been the main rallying cry of Islamism everywhere.

And Islam is defined not in the narrow terms of Sharia's legal code, but in such broad terms that make it potentially compatible with democratic values, which Muslim reformers have long called for.

This could effectively criminalise the use of religion by any political group, and thus undercut the powerful Islamist movement, Ennahda. But it is very likely to appeal to secularists.

Some of the strongest criticism of Mr Saied and his constitution have focused on the drafting process itself, which was neither transparent nor inclusive.

It was put together by a group handpicked academics. The public online consultation that was announced earlier this year has failed to attract large number of Tunisians - only 500,000, some 5% or so of the electorate.

Crucially, neither the constitution nor the president have specified the criteria for considering the document has secured wide public support.

No threshold for approving the document, nor a minimum turnout have been stipulated.

Tunisia is sharply divided between advocates of political Islam and secularism

Several parties - including the biggest block in the dissolved parliament, Ennahda - have called for a boycott.

But opposition to Mr Saied has never managed to mount an effective campaign to rally the public against the president or force him to change course.

All eyes will be on the turnout. A big turn out with a yes vote could cement Mr Saied's power. A low turnout or a no vote could plunge him and Tunisia in a deeper constitutional crisis.

Although he has been democratically elected with some 70% of the vote in 2019, failure to secure resounding popular support could further undermine his legitimacy and will most likely embolden his enemies to challenge him.

You may also be interested in:

Tunisia referendum: A nation divided