'My dad, the claw hair clip inventor'

- Published

Model Kaia Gerber wears her claw clip in classic tortoiseshell

It was the hair accessory of choice in the 1990s - fashionable yet functional - making a comeback in Covid lockdown when a trip to the salon wasn't possible.

But few people realise the claw clip started life in a humble workshop in France, and it was invented by my foster dad.

"We had a saying: 'Wherever you go in the world, you'll find a bottle of Coke, a poster of Michael Jackson and our hair clip,'" he remembers.

I was brought up in France between two families. My birth mother, Maria, is from Cape Verde off the West African coast. She fled the islands when she got pregnant with me, aged 24, eager to leave behind her life of hardship for a better future in Europe.

That meant escaping in the middle of the night to catch a plane to Guinea-Bissau. From there it was a turbulent journey of several months to reach Portugal and then France, aided by friends and family along the way.

I was born weeks later in December 1976 in Riom, a small town in eastern France. We slept on the streets in deepest winter until she discovered an abandoned shed. Her health has never been the same since.

Me with my birth mother Maria in 1977

A young French couple, Christian Potut and his wife Sylviane, heard of our plight and offered to take me in for one night, and help my mother find us a home.

Yet, somehow, I never left.

My birth mum Maria always said the Potut family would be repaid for their generosity. It turned out she was right.

Fast-forward to the 1980s - a time of big phones, big hair - and for Christian - big dreams too.

He had left school at just 14 with no qualifications but a passion for making things. Aged 27 and broke, he set up a small workshop in a 17m-sq- (180-sq-foot) old bread oven at the back of his parents' garden.

But the business slowly expanded and by 1986 Christian and Sylviane's company, CSP Diffusion, opened its first factory in our hometown, Oyonnax, making various plastic items such as hairbands, combs and even yo-yos.

Then came the moment that changed our fortunes forever.

"One day I kept crossing and uncrossing my fingers," says Christian. "And that's when I had my lightbulb moment. I said to myself: 'I sell combs and clips, why don't I combine the two?'"

And so the iconic claw hair clip was born.

"It was for any type of hair - curly, fine, thick, long, short," he says proudly.

Christian Potut explains how he came up with the idea for the iconic hair claw clip

Did having me, an African daughter, make my dad reflect more deeply on why it mattered that the designs worked for all hair textures, I ask him?

"Not really," he says, or at least it wasn't a connection he remembers consciously making all those years ago.

But their universality was right for the times.

This was an era when high fashion and the high street were growing ever closer, and claw clips were inexpensive and democratic - coveted by the rich and ordinary people alike.

"This clip takes me right back to my childhood, when my mother used it every day on her clients," says hairdresser and L'Oréal brand ambassador Alexis Rosso. "It was also a game-changer for women of colour, for whom having long, relaxed hair was in fashion at that time. This clip changed the game for women of all races."

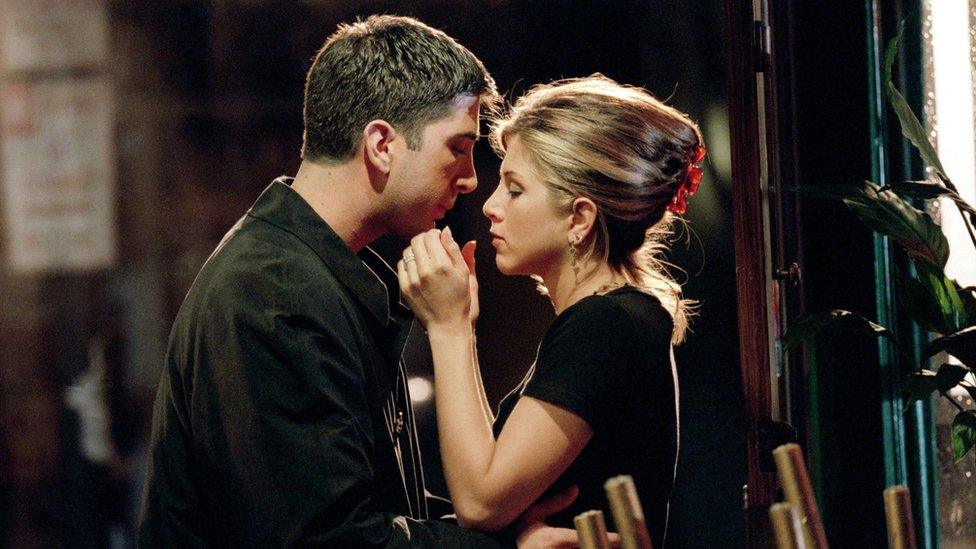

Eventually claw clips were everywhere you looked - even gracing the iconic hairdo of Rachel in the hit TV show Friends, played by Jennifer Aniston.

Friends is one of the most popular TV shows of all time

But it wasn't until all my schoolfriends kept bugging me for more and more clips that I realised just how big a hit it was.

By the mid-1990s our family company was selling hundreds of thousands of hair clips worldwide per month, the factory was extended and staff numbers ballooned to 50-odd to meet the ever-growing demand.

During school holidays I'd sit in the workshop alongside Christian and Sylviane's children, Sandrine and Jean-François, checking each clip one by one, cleaning any marks and removing any excess plastic before packing them for shipping.

One thing that stays with me is the scent of melting plastic. It may seem strange, but for me, that smell sums up warm childhood memories.

It's hard to believe the amount of work that goes into such a tiny item.

"First comes the drawing," says Christian. "Then we make a resin scale model, a plaster mould, and pour a type of metal alloy on top to give us the final mould. This mould is then attached to a huge press machine. Hot, liquid acetate is poured inside. As it cools, the claw takes shape and is injected.

"It's a real labour of love. It used to take me around 200 hours to create a single mould."

'I always knew that I was clever enough to change my life,' says Christian Potut

The biggest markets were the US and Japan, but European countries like Greece couldn't get enough of the claw clip either.

"It was brilliant... so innovative," recalls Fanny Lappas in Athens, who was one of my parents' first and biggest clients, ordering up to 100,000 clips at a time.

Today we mostly associate claw clips with classic colours like black and tortoiseshell.

But in the 1980s and 1990s, keeping up with the latest trends meant bringing in fashion and colour consultants to offer a vast palette - and enlisting the jewellery brand Swarovski for an exclusive diamanté range fit for royalty.

"One of our clients was the sole supplier for Sweden's royal family - her shop in Stockholm was like a fairy's shop," recalls my foster mum Sylviane. "She had rows and rows of our clips with rhinestones - our most expensive items - and she would sell every single one of them.

Britain also had a taste for our fresh and exciting designs. Client Paul Criscuolo tells me it was the first such clip he had seen.

"I had been in the business for years but when Christian arrived in our London office with that clip... we knew straight away that it would be big."

As the business grew, so did my parents' belief in their principles. Trust was paramount. "We sold a lot of clips, but we also made a lot of friends," says Sylviane.

Clients in the 1990s check out CSP Diffusion's latest designs

Success brought the opportunity for travel.

"I had never left our region of France before, but with this clip I was meeting clients in Tokyo, Toronto or Morocco," says Christian.

By this time I was a teenager and could speak some English, which made me an asset to the team on business trips abroad.

I was agog the first time I saw New York. We stayed in one of the city's fanciest hotels and I remember looking out of the window and promising myself that I, too, would follow my dreams.

It was hard work but there were some memorable failures too - such as the time I assembled hundreds of mis-matched clips for a very important client in New York.

Yet I learned a lot from the experience, and now double- or triple-check everything I do.

My birth mother says she doesn't regret the challenges we faced because "I knew, deep in my soul, that my daughter would avenge me and make me proud".

My foster parents opened their home and their hearts to me, gave me the audacity to dream big and encouraged me to come to the UK.

Without them all, I wouldn't be who I am today, a producer and presenter for BBC Afrique's Cash Éco programme. I was recently voted sixth-most influential African woman of the diaspora, external and in the top 100 most influential African women, external.

How amazing it is to witness the revival of my dad's invention 30 years on.

"We know that fashion tends to repeat itself - and just as ponytails and flared trousers have made a comeback, so has this vintage item," says L'Oréal's Mr Rosso.

Model Bella Hadid wearing a claw clip last year

"We still feel the same pride and excitement today when we see the younger generations wearing our clip. It's truly a classic design," says Sylviane.

But with all that success, were there any regrets for Christian and Sylviane?

"We should have applied for a patent. It was protected in France but not abroad," Christian says. "There are copies all over the world… But it's been copied because only good things are worth copying."

And I know that one thing they don't regret at all is taking me in.

"People called us mad because they were African immigrants and we barely had enough for ourselves, but when I held you in my arms, it was love at first sight," my foster dad tells me.

"When I saw you, I felt that you were mine," adds my foster mum.

Essential business tips from Christian and Sylviane Potut:

Love what you do, it's a must

Have faith in yourself and your product

Pay close attention to your clients' needs

Patent your product - coughing up the money earlier on will be worthwhile in the end

Keep new projects close to your chest, only telling the people you trust.

Related topics

- Published19 May 2021

- Published4 March 2021

- Published23 January 2019

- Published23 April 2019

- Published20 December 2018