Kenya-EU trade deal: Why the East African Community was left out

- Published

Kenya's President William Ruto is confident that the trade deal will boost local industries

Kenya's President William Ruto hailed his country's "remarkable partnership" with the European Union (EU) as the two sides inked a 25-year trade deal, but it has raised questions about East African unity.

Has the region's economic powerhouse undermined that unity or did it have little choice but to go it alone?

That's been a major point of debate all week - and it's likely to intensify once we get official reaction from the six other states in the East African Community (EAC) - the regional trading bloc that, some believe, should have been at the heart of the agreement with the bigger and more powerful EU.

So far, they have been silent, but the deal - the most comprehensive agreement that Kenya has ever negotiated with the EU, locking in both sides for 25 years - seems to fly in the face of the position of at least the Tanzanian government.

It said in a statement last year that it would only support an agreement that benefited the EAC at large - not just Tanzania.

Kenya's decision has certainly irked lobby group Econews Africa, so much so that it's threatening to go to court to challenge it.

Econews Africa's executive director Edgar Odari argues that Kenya has "effectively jumped the gun, opened up new negotiations with the European Union, [including] a new chapter on trade and sustainable development and gone ahead to get it signed by President [Ruto]".

Kenya did ink an EAC-brokered deal with the EU in 2016, but it never fully came into effect as most other members of the regional bloc refused to sign it.

Backers of President Ruto's bilateral deal accuse them of dragging their feet over finalising that agreement, resulting in Kenya suffering the most.

They point out that Kenya is the only EAC member that falls in the category of "emerging" country, while the rest are classified as "least developed", meaning their exports could continue to enter the EU market without a deal.

So, Kenya had to strike its own agreement - or risk losing access to the lucrative market.

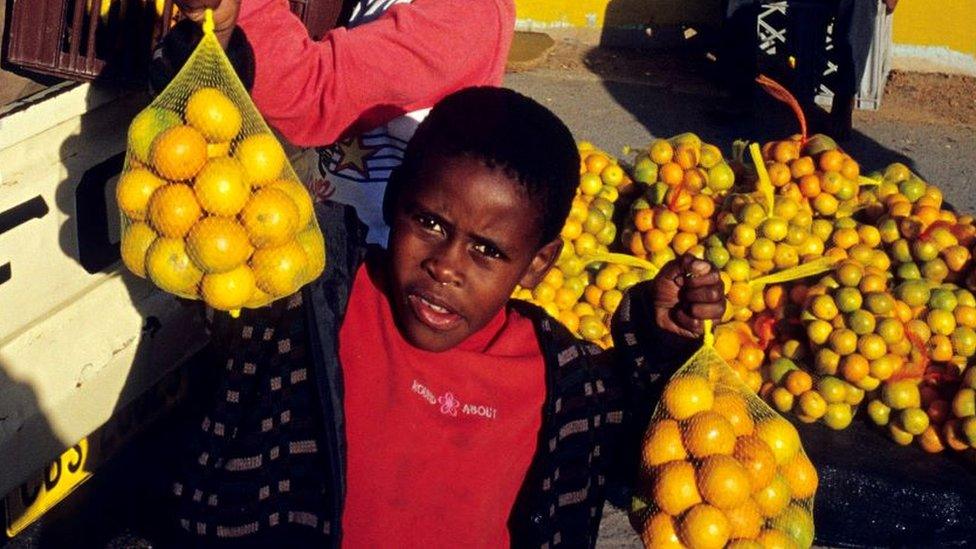

Kenya is a major exporter of flowers to Europe

The 27-nation EU is Kenya's second-biggest trading partner, after China, and Kenya's most important export market.

The EU mainly imports vegetables, fruits and flowers from Kenya to the tune of $1.3bn (£1bn), while exporting mineral and chemical products, as well as machinery, to Kenya worth $2.2bn.

Kenya's presidential spokesperson Hussein Mohammed hailed the agreement, saying it would:

boost investment in the manufacturing sector

create jobs in various industries

position the country as a hub for European companies trying to enter the East African market

give Kenyan farmers duty-free access to their biggest export market

However, Kenyan officials have said very little about the fact that the deal gives the EU unfettered access to the Kenyan market, and the reduction of tariffs over a 25-year period.

Concerns abound that this could lead to European products flooding Kenya to the detriment of local industries.

To address these concerns, the government will have to help Kenyan businesses to scale up to stave off competition from much bigger European players, while ensuring exports to the lucrative EU market increase.

It is confident that it is up to the challenge, so much so that it is looking at sealing a bilateral trade deal with the US next year, raising the question of what this means for efforts by African states to create a united trade front.

Related topics

- Published1 July 2022

- Published27 January 2021

- Published4 July 2023