Pakistan's murky cricket-fixing underworld

- Published

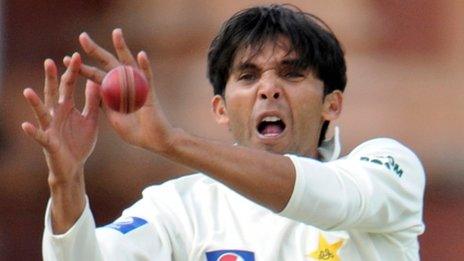

Mohammad Asif is preparing to serve a jail term for his part in the spot-fixing scam

Now that three Pakistani cricketers and an agent have had jail terms for their part in a spot-fixing conspiracy dished out, the suspicion is that the betting scam may actually have been much wider.

Suggestions from the courtroom in London imply that several other Pakistani players may also be involved and names were tossed around the court hearings on Monday and Thursday.

The media in Pakistan also reported on Thursday a news story carried by The Cricketer magazine saying secret deleted text messages uncovered by Scotland Yard and placed on the court's record reveal that every single match played by Pakistan in England last year was targeted by bookies.

So what was going on during Pakistan's cricket tour of England in the summer of 2010?

An idea of the febrile atmosphere is provided by Pakistani fast bowler Shoaib Akhtar, who was on the Pakistani squad during that tour, in his recently released book, Controversially Yours.

"I desperately wanted us to play well," he writes, "especially in preparation for the World Cup… but I was also fighting to stave off demoralisation. I had started by trying to become a mentor to the youngsters, but now I didn't know whom to trust."

In one of the one-day matches at Lord's, he recalls English player Paul Collingwood telling him that Pakistan was involved in match fixing.

"I kept repeating, who does? He was clearly bitter and claimed that I was totally blind." Later, Akhtar says in the book, he watched in despair as Jonathan Trott called Wahab Riaz a fixer during a net session.

Bookie 'match-fixers'

Many in Pakistan feel that the fact that Pakistani cricketers continue to fall prey to bookies is because the Pakistan Cricket Board has repeatedly failed to nip the evil in the bud.

Pakistani fans have said they feel betrayed by the actions of the cricketers

"We have seen similar episodes in the past… but it is happening again," former Pakistani cricketer Aamir Sohail told the BBC.

"Unless you learn from these and introduce reforms… I'm afraid this will continue to happen in future."

Shamimur Rahman, a Pakistani journalist, had his first brush with a bookie when he went to cover a Pakistani Test series in South Africa in the mid-1990s.

"The man was calling from India. He somehow found my number and rang me up before a match to know about weather conditions. He was apparently weighing odds for early betting."

Rishad Mehmood, sports editor of Pakistan's Dawn newspaper, says bookies have now morphed from simple gamblers to match fixers.

"From the 1980s through 1990s, bookies cultivated players and journalists and got into a position where they could offer huge sums of money in confidence to players to under perform.

"By the mid-1990s we were faced with a situation where a large number of senior players in several teams of the world had become virtual members of the match fixing mafia."

Mr Mehmood says that while the cricket boards in India and South Africa moved quickly and firmly against erring players, the Pakistanis remained complacent.

"What we have seen recently is nothing but the power of the bookies over players which we have ourselves allowed to pervade the game," he says.

A budding cricketer, Zulqarnain Haider, deserted the Pakistani team in Dubai in November 2010, saying he was being threatened by bookies to fix matches in a series against South Africa.

He later accused a close relative of one of the top players of the Pakistani team of being in league with the bookies. The accusation was denied.

Some analysts point out that such temptations are especially acute in Pakistan because players there do not have the opportunities - through sponsorship or lucrative domestic leagues such as the IPL for example - that players in other major cricketing nations may have.

And the judge expressed some sympathy for the youngest and greenest of the cricketers to be sentenced, Mohammad Amir.

"You come from a village background where life is hard. You were only 18 and readily lent on by others."

These resonate with concerns about the role of agents and their considerable influence over impressionable young players.

The judge told agent Mazhar Majeed, external on Thursday that his position as manager to half a dozen members of the Pakistani team "meant that you... were in a position to influence other players in the team as you did."

'Paid to under-perform'

But many in Pakistan feel match fixing has become a family business for many cricketers.

In 2000, a young Pakistani bowler, Ata-ur-Rehman, submitted a written statement on oath before a judicial inquiry naming three top cricketers of the time as having offered him big money to under perform at a match in New Zealand.

The cricketers will have to serve out jail terms in UK prisons

According to his sworn affidavit, he was offered 300,000 rupees ($3,488) for bowling loose deliveries in three overs.

He alleged he was paid this money, and asked to bowl four more loose overs in the next match, which he said he didn't and was afterwards manhandled for it by a senior team member.

Subsequently, Ata-ur-Rehman retracted his statement, but weeks later showed up again at the inquiry to reconfirm his original statement.

He said he retracted his statement because his brother, who was playing county cricket in London, had gone missing and he had received phone calls saying if he didn't retract, his brother may be harmed.

He said his brother had now been recovered and was safe.

Dawn newspaper's sports editor, Rishad Mehmood, was summoned to the same inquiry.

He was asked to explain how his then newspaper, The News, had in a report predicted that Pakistan - then a favourite - may lose to minnows Bangladesh more than 20 days before the match.

Pakistan actually lost to Bangladesh, who were subsequently awarded Test status by the International Cricket Council (ICC).

Mr Mehmood is not willing to share details, but he alleges this and many other decisions were taken at a meeting of a number of senior players in the World Cup squad weeks ahead of the tournament to draw up the team's strategy.

"All junior players at the time - such as Shoaib Akhtar and Shahid Afridi - were sitting outside, sulking, while the representative of a known underworld don who was blamed for the 1993 bombings in Mumbai, was inside, in the meeting," he says.

- Published3 November 2011

- Published3 November 2011