Bangladesh finally confronts war crimes 40 years on

- Published

Ferdousy Priyabhashini says she was a victim of Pakistani war crimes

Like many other Bengalis, eminent sculptor Ferdousy Priyabhashini is happy to see those accused of mass murder and rape during Bangladesh's 1971 independence war finally stand trial.

Ms Priyabhashini was 23 at that time, when a group of Pakistani soldiers and their Bangladeshi associates stormed into her house and dragged her away. Her husband and three children watched helplessly as she was bundled into an army jeep.

For seven months, she was repeatedly raped and tortured at an army camp in the capital Dhaka, she says.

"I was subjected to extreme physical and mental torture. They had no mercy. Many of my friends and relatives were killed in front of me," she said.

"It is heartening to see, 40 years after those atrocities, that some of those responsible for those gruesome acts are in the dock," Ms Priyabhashini said.

Violent birth

Bangladesh is yet to come to terms with its violent birth in 1971, after the Pakistani government sent in its army to stop was what was then East Pakistan from becoming independent.

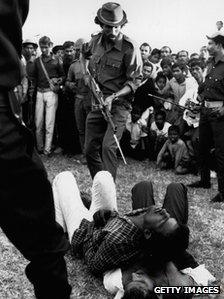

Suspected collaborators were sometimes killed by their captors.

It is not exactly clear how many people died, but official figures estimate that more than three million people were killed and hundreds of thousands of women raped during the nine-month bloody battle.

The minority Hindu community was particularly targeted. Many Hindus were even forcibly converted to Islam.

The war ended with the surrender of Pakistani forces to India, which intervened after millions of refugees flooded its eastern states to escape the brutality.

Soon after the war, there were demands from the victims and human rights groups to try those responsible for the slaughter, rape and looting.

However, Delhi, Dhaka and Islamabad agreed not to pursue war-crimes charges against the Pakistani soldiers, who were allowed to go back to their country.

Collaborators pursued

Despite various attempts, efforts to try those Bangladeshis who allegedly collaborated with the Pakistani forces did not materialise until last year.

In 2010, for the first time, the Awami League-led government set up the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) to try those Bangladeshis accused of collaborating with Pakistani forces and committing atrocities.

So far seven people, including two from the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party and five from the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami party, have been arrested and are facing trial in Dhaka. All of them deny the charges.

The Jamaat-e-Islami is the country's largest Islamist party and it opposed Bangladesh's independence from Pakistan at that time. Some of its members allegedly fought alongside the Pakistani army.

However, the two opposition parties accuse the government of carrying out a vendetta and trying to use the trial to curb their political activities.

"The trial will be transparent and independent. International observers will be allowed to come and watch the trial. The accused will be given full opportunity to defend their case," said the Bangladeshi law minister, Shafique Ahmed.

Despite the overwhelming public opinion in support of the trial, there are some bottlenecks.

Fair trial doubts

The leader of Jamaat-e-Islami is accused of more than 50 killings during the war.

First of all, this tribunal is almost a domestic set-up and the three judges sitting on the tribunal are from Bangladesh. The United Nations and other international agencies do not have any major role to play.

Human rights groups said some of the rules were not consistent with international standards, as followed by war crimes tribunals in Rwanda or Cambodia.

"Bangladesh has promised to meet international standards in these trials, but it has some way to go to meet this commitment," Human Rights Watch said in a statement issued earlier this year, external.

Defence counsels also complained about a lack of time for their team to prepare for the case. They also argued that Bangladesh didn't have the expertise to try war crimes, so the trials could not be fair.

"Both prosecution and defence do not have sufficient training in a trial of this magnitude," argued Abdur Razaaq, a senior lawyer for the accused and also a leader of the Jamaat.

"Our legal infrastructure is also not adequate to handle this case. So, how we can expect a fair trial?"

'Culture of impunity'

However, the government vehemently argued that it had enough legal expertise and manpower to conduct the trial. It promised that there would not be any political interference or revenge.

Despite the debate over whether or not the tribunal meets international standards, there is broad agreement in the country that the trial is long overdue. The consequences are likely to be severe if it doesn't go ahead this time.

"The trial will put an end to the culture of impunity, said Aly Zaker, an eminent writer and director.

"If not, the peace and harmony which the people of Bangladesh are trying to practise can be totally destroyed. So this trial is very important for our country and our people," he said.

- Published3 October 2011

- Published10 August 2011

- Published16 June 2011