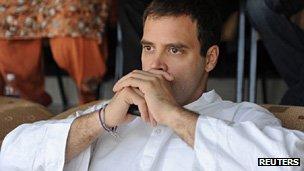

Waiting for Rahul Gandhi

- Published

- comments

Rahul Gandhi is India's prime minister in waiting

It's that time of the year again for India's febrile media - the time to resurrect Rahul Gandhi, external, scion of the Gandhi dynasty and India's prime minister-in-waiting.

It's time to tell the world again that the 41-year-old heir apparent is finally gearing up to lead his party, and in the event of a victory in the general elections in 2014, the government too. The reason to resurrect Mr Gandhi is also familiar: Mr Gandhi kicked off Congress's election campaign in Uttar Pradesh last week.

For the last six years or more, Indians have been hearing that the mild mannered dynast - educated at Harvard and Trinity College, Cambridge - has finally come of age. It is the media's favourite, and laziest, political narrative. The problem is that possibly nobody, maybe not even Mr Gandhi himself, quite knows when he will finally take the big plunge.

There was an avalanche of speculation about Mr Gandhi's move from what senior journalist MJ Akbar calls the "waiting room to the head office" when he was made the general secretary of the party, external in 2007. We heard more of the same when he launched his so-called 'Discovery of India', external tour in 2008, travelling to the countryside and having sleepovers in the homes of dirt-poor Dalits - formerly known as "untouchables".

There has been more of the tired conjecture recently: when Mr Gandhi's mother and Congress party chief , external handed over power to a group of leaders, which included him, during her five-week , external in the US; when Mr Gandhi lashed out at the Uttar Pradesh government for forcibly acquiring farmlands. Mr Gandhi had arrived and was poised to lead the party into battle, we were told every time.

Luxury

Rahul Gandhi, clearly, enjoys the luxury of several comings.

Mr Gandhi has his task cut out. His latest resurrection is happening at a time when his government's image is at an all-time low. The party has been relegated to an enfeebled alliance partner in key states like Tamil Nadu (last time Congress won an election here was in 1962) and West Bengal (last election victory was in 1972).

Mr Gandhi launched his party's election campaign in Uttar Pradesh

Not surprisingly, Mr Gandhi is trying to revive the fortunes of his party in the politically crucial state of Uttar Pradesh, which hasn't seen a Congress government in a quarter of a century - the last time the party even inched close to 100 seats was 20 years ago.

How much Mr Gandhi is able to revive the Congress in the heartland of Indian politics may well determine his - and his party's - future. India's most populous state sends more than 80 MPs to parliament, and is the historical political base of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty.

It won't be easy despite what critics call a record of misrule by the remote expensive statues., external Health care and education is in a shambles. Corruption is all pervasive.

As with most politicians, Ms Mayawati's record in power has been mixed. Even her worst critics will agree that Ms Mayawati and her party have contributed to significant empowerment of the Dalits. She has ensured good prices for farm produce. She has sped up urban works in many cities and towns in Uttar Pradesh. Politically, she has a vast network of dedicated party cadres compared to the fractious and dishevelled Congress.

Most believe that Mr Gandhi is right to take on Ms Mayawati on the issues of governance. But his critics say that he hasn't displayed the same charisma and political acumen. They see him more as an urbane, city-bred interloper, parachuting into the "other India", commiserating with the poor, and then returning to Delhi.

All time low

Mr Gandhi has launched his party's campaign at a time when his government's image is at an all-time low. It is reeling under allegations of corruption, policy paralysis, bad governance and an inability to check inflation. The middle class is peeved with interest rates hikes which put on hold their plans to buy homes and cars. "I think Rahul Gandhi is making the biggest mistake in thinking that political mobilisation and outreach can happen independently of your record in government," analyst Pratap Bhanu Mehta, has said. "That somehow you can be a big national leader without taking a clear public stand on the major issues of the country."

Mr Gandhi has travelled the countryside to connect with the poor

Apart from a speech in the parliament, Mr Gandhi has not spoken on how to tackle corruption, a cancer eating away at the country's vitals. He is a votary of inclusive growth, but Indians have no idea of his vision for India's economy in a fast changing world. Mr Gandhi has been silent on the much-needed public reforms, without which India will not be able to seize the initiative. His views on joblessness, education, the contentious debate over development and environment and affirmative action are virtually unknown.

Mr Gandhi's supporters defend their leader stubbornly. They point to media reports about how he has revitalised and democratised the flagging youth wing of the party, and inducted bright young men and women into its ranks.

This exercise, they say, threw up a bunch of young parliamentary candidates in 2009. But, as many point out, the Congress remains a deeply hereditary party - 37% of the MPs are hereditary compared to 19% hereditary MPs in the main opposition BJP. Real power - as with most other Indian parties - still rests with unimaginative, geriatric leaders. The younger MPs of the party, mostly privileged, rich dynasts themselves, have shown no spark or imagination either, say critics. Mr Gandhi's much-hyped party reforms have begun to look as disturbingly still-born as his father Rajiv Gandhi's famous pledge rid the Congress of power brokers.

The question is not whether Rahul Gandhi will become the prime minister. "The job comes to him by genetic entitlement, not electoral endorsement," as MJ Akbar puts it. But will Mr Gandhi make a good prime minister?

The jury is still out. India is a restless and aspirational country, and Mr Gandhi, say his critics, has been found wanting in addressing these aspirations and in bringing hope. There is nothing inspiring about his speeches, in the way, believe many, Nitish Kumar, the energetic Bihar chief minister, talks about a vision to rebuild his backward state. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta says, it is not enough to "come up to people and say, 'Hi trust me, I am a good guy'. It doesn't work like that".