Lessons from the death of North Korea's first leader

- Published

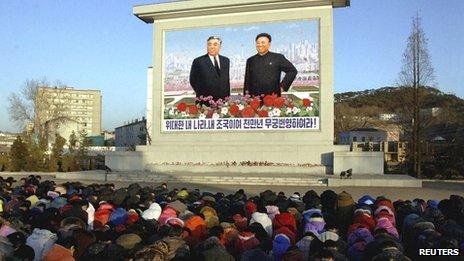

Tributes and mourning for Kim Jong-il may well follow the public pattern seen for his father in 1994

When North Korea's "Great Leader", Kim Il-sung, died suddenly in July 1994, the country was immediately plunged into a power struggle that has never been resolved.

As the period of mourning began, reports emerged of troop movements in Pyongyang and other major cities as different factions of the military and the ruling party rushed to consolidate their positions.

That Kim Jong-il would succeed his father was not in doubt, but the level of his control over secretive state institutions was a complete unknown.

Negotiations with the US to dismantle North Korea's nuclear weapons' programme had broken down the previous year, and the US administration was preparing for the possibility of the collapse of the regime and - in a worst-case scenario - war.

Amid all this, the BBC was allowed in, with the invitation itself proving to be evidence of the tensions under the surface.

In the week that we were chaperoned around, open arguments broke out between minders - often in front of us.

Our first stop was a huge Pyongyang art gallery where artists were working round the clock on portraits of Kim Jong-il. Stacked up under high ceilings, they showed North Korea's new leader taking command in an array of places - farms, factories and on warships.

But one minder told me under his breath: "He is only the Dear Leader. It'll be years before they are shown."

Our next visit was to a badge-making factory where new red lapel badges of the "Dear Leader" were tumbling out of a machine. One minder explained the factory was working overtime to meet the huge demand of the people. Another insisted they would be held back until it was "safe" to be seen wearing one.

The badges were apparently related to the ruling party and therefore might not have been viewed with sympathy in places where the party and the military were at odds.

Sticking together

In a long interview with a senior party official, we were told that this was an opportunity for North Korea to open up for reform. I later heard that he had lost his particular power battle. He had been executed for corruption.

Residents of Pyongyang have been shown crying in the streets following the news of their leader's death

Our minders were young men, mostly educated in China, Russia, even Malta, and we never knew exactly which institutions commanded their loyalty.

Over evening drinks they would crack hilarious jokes.

One night, the conversation turned to America and the 1969 moon landing. Despite their differences, our highly intelligent guides became deadly serious, insisting that this historic event had never happened because North Korea would be the first country to send a man to the moon.

While Kim Il-sung held absolute sway over his country, under Kim Jong-il it slid deeper into poverty and further towards military confrontation.

In 2006 and 2009, it carried out nuclear tests. In March 2010, it sank a South Korean patrol boat. And in November 2010 it shelled an island near the disputed border.

Tributes and mourning over the next few days may well follow the public pattern seen in 1994.

One similarity is the delay - under the traditions of Confucian mourning - between the death of Kim Jong-il on Saturday and the announcement more than a day later. The regime kept the secret so well that the South Korean President, Lee Myung-bak, only knew about it from the television news.

Rivalry may run high underneath, but in a crisis, North Korea's secretive and ruthless leaders have a track record of sticking together.