Will China's rise shape Malaysian Chinese community?

- Published

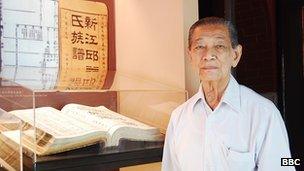

Khoo Boo Hong says overseas Chinese are no longer seen as the rich ones

In Malaysia's northern state of Penang, a distinct shift is being felt in the immigrant Chinese community, as it rides the wave of China's economic rise.

The Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi, one of the richest clan associations, used to send money back to their ancestral home in Fujian province, China.

But that is changing as places like Sin Aun, a fishing village that the clan members' families hail from, are now bustling and have no need for money sent from overseas.

"In the past, overseas Chinese were seen as more wealthy but now the Chinese from China are even richer than us," says the clan association's Khoo Boo Hong.

Indeed, Chinese money is becoming more visible in Penang. A bridge that is currently under construction is being partly financed by a cheap loan from the Chinese government. The 4.5bn Malaysian ringgit (US$1.4bn) project is set to be the longest bridge in South East Asia, stretching 24km (15 miles).

The Chinese community in Malaysia acts as a bridge for business opportunities in China.

In 2010, Malaysia was one of China's biggest trading partners from South East Asia. Two-way trade hit 147bn Malaysian ringgit (US$46.3bn) last year, with a push to more than double that amount by 2015.

'Special relationship'

Much of the trade has been established by the Chinese Malaysian community, says Oh Ei Sun, the former political secretary on Chinese affairs to Prime Minister Najib Razak.

Malaysia was the first South East Asian country to form diplomatic ties with China in 1974.

As a result the two countries have a special relationship, and the Chinese in Malaysia have tried to exploit this kinship by developing business ties with China, says Mr Oh.

The Chinese began arriving on Malaysian shores in the early 15th Century. Today, they make up 24% of a population of 28 million, and have always been more prosperous than other ethnic communities. According to a 2011 Forbes magazine list, eight out of the top 10 richest Malaysians are ethnic Chinese.

This wealth imbalance has fuelled long-standing resentment among the Malay majority. It erupted into deadly race riots in 1969 - violence that two years later led the government to implement an affirmative action plan called the New Economic Policy.

This gave ethnic Malays and indigenous groups privileges over the Chinese and Indians, such as cheaper housing, priority in university scholarships and civil service jobs. The policy officially ended in 1990 but it has been succeeded by similar plans.

Lim Cheah Chooi hires Malaysian or Singaporean Chinese managers for his factories in China.

"The quota system is still in place on so many levels," says Teo Nie Ching, a lawmaker from the opposition Democratic Action Party. This limits job prospects for Malaysian Chinese in certain businesses, including listed companies, she says.

"After so many generations [the Chinese] still feel that we are second class citizens," Ms Teo says.

Analysts say this sense of alienation has made many Malaysian Chinese look for opportunities elsewhere, including China.

Speaking the language

As the Chinese economy opens up, Malaysian Chinese act as a bridge because many are educated in the United States or Britain but they can also understand the Chinese language and culture, says Lim Cheah Chooi.

His engineering firm, Unimech Group Berhad, has production factories in China, but he employs Malaysian or Singaporean Chinese at the middle management level.

This is something you see even among local Chinese companies who export to the West, says Mr Lim.

"How many people can say they speak Mandarin, multiple Chinese dialects, Malay and English? Most Malaysian Chinese can," he says.

This advantage is maintained because of Malaysia's multilingual education system. Ethnic Chinese and Indians can choose to study at the primary level in their mother tongue.

With the rise of China, more and more people, including non-Chinese, want to learn Mandarin, says Yong Yeow Khoon, CEO of the Chinese-language newspaper Guang Ming Daily in Penang, who is also a board member at an independent Chinese school.

The number of non-Chinese in Chinese vernacular schools is estimated to have grown to over 60,000 over the last three decades.

Even the Malay prime minister has sent his son to learn Mandarin at the Beijing Foreign Studies University.

Optimists point to this as a sign of increasing acceptance of Chinese culture by the Malay community. But some say this is wishful thinking.

Attitude change?

Although the government has been pushing for national unity through the 1Malaysia slogan, analysts interviewed by the BBC do not believe that there is a fundamental change in attitude towards the Malaysian Chinese.

Economist Cheong Kee Cheok, who used to work for the World Bank, says some Malays do not distinguish between the Chinese from China and the ones from Malaysia.

"Malaysia in some ways is hostage to its own politics," says Mr Cheong.

He also says that Malaysia needs to be more aggressive in accessing the Chinese market. It may have had a head start in China, but "unfortunately...never used this advantage".

He believes much more can be done to facilitate relations between the two countries. At the moment most businesses who get into China are through the individual efforts of Malaysian Chinese businessmen, he says.

He says Malaysian leaders are not serious about China's rise.

The latest visit from Chinese premier Wen Jiabao in April could lend credence to this theory.

Malaysian blogs were filled with complaints about the grammatical mistakes on the welcome banner put up for Mr Wen in Chinese, suspected to be roughly translated from Malay.

Interpretations vary but the Chinese banner read: "Official welcoming ceremony, with him together his Excellency Wen Jiabao official interview Malaysia."

Many comments on Lowyat.net forum said that was shameful, given that ethnic Chinese people form the second-largest population in this multi-racial country.

"What do you expect? No Chinese working in government," wrote automan5891.