Can Pakistan step back from the brink?

- Published

The murder of Salman Taseer was both the start and the symbol of Pakistan's unravelling in 2011

One year ago, Pakistan was shaken when leading politician Salman Taseer was murdered by his own bodyguard. His violent death and the lack of government response were merely the beginning of a turbulent year for the country. Writer Ahmed Rashid considers whether Pakistan can step back from the brink in 2012.

The death of Salman Taseer, governor of Punjab province, now appears as both the start and the symbol of the political, economic and social unravelling of Pakistan that has taken place since that fateful 4 January day.

The gruesome aftermath of his death, when the governing Pakistan People's Party, the army, the mullahs and civil society appeared to deny the reality of what had happened, made many Pakistanis ashamed of their rulers.

Roses for a killer

Mumtaz Qadri, an elite police force member, pumped 27 bullets into the politician as he was walking back to his car after lunch at an Islamabad restaurant.

Qadri had informed his police colleagues standing nearby that he would commit murder and throw down his weapon, so there would be no need to kill him. The police obliged by giving no warning to Taseer or shooting Qadri dead.

Qadri, who belonged to a small Islamic group called Dawat-e-Islam, said he killed Taseer because of his attempts to change the controversial blasphemy law. He was showered with roses when he made his first appearance in court.

Hundreds of lawyers pledged to defend him and he was treated as a celebrity by many.

Qadri was showered with roses when he appeared in court

Qadri was later tried and sentenced to death but he has appealed against the sentence.

Meanwhile Asia Bibi, the jailed Christian woman whose case of alleged blasphemy had so appalled Taseer, continues to grow weaker in jail and more isolated. There are fears that a zealous prisoner or guard in jail may try to kill her.

When Taseer's funeral was held, no cleric could be found in Lahore who would read his funeral prayers out of fear of the extremists - some of whom declared that the dead Taseer was no longer a Muslim.

The country's few liberal civil society members tried to counter the wave of intolerance that swept the country by holding small but ultimately meaningless demonstrations.

More important was the reaction - or total lack of it - by the government, the army, parliament and the political parties. There was no public condemnation of the murder by the highest authorities in the land, except for politician Sherry Rehman, now ambassador to the US.

More sectarian attacks

As if the family had not suffered enough, Taseer's son Shabaz was kidnapped by an extremist group in August and has not been heard of since.

Taseer was a multi-dimensional politician, businessman, writer and raconteur but he seemed to move to another level when he became governor, taking up controversial issues and defending human rights which even the government was too scared to do.

His death a year ago has brought many consequences.

During the past year, no politician has dared raise the issue of reforming the blasphemy law. Intolerance by extremists against both Muslims and non-Muslims has increased enormously and there has been a dramatic rise in the number of sectarian attacks, which are usually perpetrated by Sunni extremists against Shia citizens.

The Pakistani Taliban has continued to carry out brutal suicide attacks against the army and civilians and appears to be in control of more territory in Pakistan and also in Afghanistan's Kunar province.

The meltdown in relations between the US and Pakistan started just two weeks after Taseer's death, when Raymond Davis, a CIA operative, killed two gunmen in Lahore. The wave of anti-Americanism that followed prepared the ground for a much wider outbreak months later.

The killing of Osama Bin Laden by US special forces in May resulted in the biggest crash in US-Pakistan relations.

After that, alleged leaks from Pakistan's intelligence agency, the ISI, forced two successive CIA station chiefs in Islamabad to leave the country.

Later, the US stepped up confrontation by demanding the ISI curb attacks inside Afghanistan by the Pakistan-based Haqqani network.

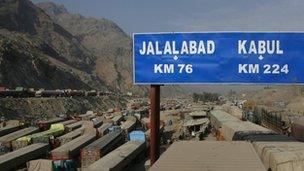

When Islamabad shut down the Nato supply route through Pakistan after Nato mistakenly killed 24 Pakistani troops, all links between the two military establishments were severed.

Looking ahead

Pakistan shut down the Nato supply route through after a Nato raid killed Pakistani troops

The government steadily lost credibility, authority and power as its conflict with the army and the opposition became worse, the economic crisis deepened and the country suffered severe energy shortages. The army also lost credibility. and the government accused the army and the Supreme Court of ganging up against it.

Taseer's killing is a watershed from which the government has not seemed able to recover and from which the extremists drew strength, increasing their defiance against a state that was deemed weak and vulnerable.

In the new year, the fear of more political assassinations lingers as do deepening divisions between the army and the government which would make the country ungovernable.

It is clear that the 50-year-old source of Pakistan's continuing instability - civil-military relations - is going to determine the course of 2012.

The army appears determined to oust President Asif Ali Zardari while he and his government appear determined to hang on. Taseer would have made a good mediator between the two because he had solid relations with both; however, there is no such figure in the political spectrum now.

Perhaps the only solution is early elections, possibly by the late spring or early summer, rather than in 2013. Pakistanis can only hope that by taking Taseer's life and death as an example, all sides in the present crisis in Pakistan can step back from the brink.

Ahmed Rashid's book, Taliban, was updated and reissued recently on the 10th anniversary of its publication. His latest book is Descent into Chaos - The US and the Disaster in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia.

- Published5 January 2011

- Published31 December 2011