Karachi polio killings: The price of prevention

- Published

Pakistan is the only country where there is public opposition to immunisation programmes

Health workers battling polio in Pakistan are paying a heavy price for their efforts.

Tens of thousands of them hit the streets every couple of months to immunise millions of children across the country, and they do it despite a growing risk to their lives.

Pakistan is one of only three countries that are still polio endemic, with a potential to spread this crippling disease to areas where it has been eradicated.

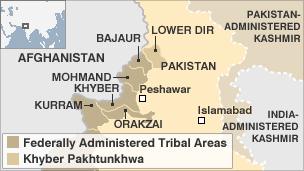

Groups wielding influence over large areas, especially in the north-west, strongly oppose the campaign.

For the most part, the reason lies in attempts by regional religious groups to create space for themselves in a wider movement of religious militants that partly or wholly drew strength and support from elements in the powerful security establishment.

The World Health Organization launched its polio eradication initiative in Pakistan in 1994. Under the programme, it provided technical and financial support while the provincial health departments provided the field staff.

The campaign made steady progress over the next 10 years, and the incidence of polio hit its lowest point, with only 28 cases reported in 2005.

Crying foul

But that year is also marked by the advent of so-called Mullah Radio, an FM channel run by Maulana Fazlullah, who went on to lead Taliban militants in the north-western district of Swat.

He was the first cleric to use his radio sermons to create hostility towards polio immunisation campaigns, calling it a conspiracy by the Americans to sexually sterilise children and thereby control the population of Muslims.

The sermons created quite a stir in Swat, and led to the country's first-ever attacks on health workers by members of local communities.

This kind of public response was not lost on clerics elsewhere who were using FM channels to create a following.

Within a year, more than half a dozen FM channels across the north-western tribal region were crying foul about the polio eradication campaigns, poisoning the atmosphere for health workers.

With time, religious groups thought up other reasons for defying the immunisation programme, such as the argument that the health workers were being used by foreign powers to spy on locals.

This argument found impetus when a Pakistani doctor was accused of running a fake vaccination campaign to help the American Central Intelligence Agency locate al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden in a house in Abbottabad.

During the last five years, health workers have been roughed up in communities, or even kidnapped and killed by organised groups.

Earlier this year, the militant groups controlling the Waziristan tribal region refused to allow vaccination of children - the first unofficial blanket ban across an entire geographical region. The authorities were hoping to vaccinate about 250,000 children in Waziristan.

As a result, the incidence of polio has been on the rise, reaching 198 cases in 2011. Most of these cases are reported to be from the north-west.

According to the provincial health department in Peshawar, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and the adjoining tribal region accounted for 45 out 56 cases reported in the country during 2012.

Targeted by snipers

Officials indicate that the situation in Pakistan is partly to blame for a polio epidemic in neighbouring Afghanistan, and also a recent outbreak in China.

There are also fears that the virus strain may cross borders into India, where no polio cases have been reported this year.

Hostility by religious and militant groups may not be the only impediment to the eradication of polio in Pakistan.

The immunisation campaigns have suffered in areas where military operations are ongoing, or where rain and floods have uprooted populations and disrupted communications for long periods during the last two years.

But the spread of militancy has been a major factor and, as the incidents in Karachi show, it is now snipers employed by organised militant groups who are targeting health workers rather than individuals in hostile communities.

In coming days, many of the roughly 80,000 field workers across Pakistan, however needy they may be, will be forced to ask themselves whether the 1,500 rupee ($15) fee they will receive for a three-day campaign is worth the risk.

- Published18 December 2012

- Published26 November 2012

- Published17 October 2012

- Published17 July 2012

- Published24 May 2012

- Published20 February 2012