The families fleeing Pakistan's militant infighting

- Published

Mohammad Saeed (far right) and his family had to flee their homes on foot

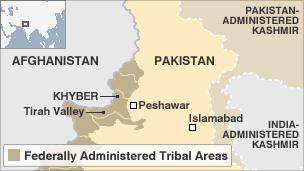

Mohammad Saeed and Mumtaz Gul from Pakistan's north-western Khyber tribal region are the latest statistics on Pakistan's swelling chart of internally displaced persons (IDPs).

But their stories, like many others, are sadly human and poignant.

They are among approximately 3,000 people who have fled the latest militant infighting in Khyber.

They are now fighting a frustrating battle to secure government help for food and shelter.

I met them outside the registration office of Jalozai camp for IDPs, some 30km (19 miles) east of Peshawar city, the regional capital.

"The officials here say they haven't been notified about our displacement, and so we can't be entitled to life-saving assistance," says 36-year-old Mohammad Saeed.

.jpg)

Crucial supply routes between Pakistan and Afghanistan run across the Takhtakai valley

"They say we will be registered as IDPs by the Khyber tribal administration. But I was at the Khyber offices in Peshawar yesterday, and they told us we'll be registered by the Jalozai camp officials."

Thus caught in the bureaucratic red-tape, he has rented a ramshackle house in a village some 15km (9 miles) north of Peshawar for $20 (£13) a month, in order to provide shelter for his family.

For the likes of Mr Saeed, this is a case of double jeopardy - first you scurry for safety, then you shuttle between government departments to find out which one will certify you as a displaced person.

Bombshells across the valley

We drive to his house, and sitting on open ground outside, he gives me an account of his escape.

In the first week of February, his native Takhtakai valley - located in Khyber's picturesque Tirah region - was simultaneously hit by heavy snowfall and fierce battles between four different militant groups vying for control.

Takhtakai's strategic value is obvious to those who know the area. It is one of the highest human settlements in Tirah, overlooking both a Pakistani military supply route to the border with Afghanistan in the north, and the Taliban-infested Orakzai region in the south.

The local tribe held back the militants for four long years, until the fighters of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) group of Taliban joined forces with an erstwhile rival militant outfit, Lashkar-e-Islam, and stormed the posts of the tribal defenders.

"Bombshells flew across the valley for a day, and by the evening there were reports about the outer posts having fallen and most local fighters having been killed," Mr Saeed recalls.

Fearing Taliban reprisals, people started to flee, leaving their cattle and their winter food stocks behind.

"I herded 13 members of my family - among them three women and eight children - down the winding mountain trails for four days, and reached Peshawar without losing a single one of them," he says.

Not everybody was as lucky though.

Mumtaz Gul, 50, who fled Takhtakai with 25 members of his family, speaks of children and older people having died or gone missing.

"Among several other families fleeing the fighting, there was one woman who had not had time to properly dress her 18-month-old son," Mr Gul says.

The child caught pneumonia and died on the second day of their flight.

"We made a stop for about two hours to hold a funeral and dig a grave for the child. The mother seemed devastated.

"She had tried to cover the boy with her shawl, but couldn't keep him warm and walk through three feet of snow at the same time," he says.

Mr Saeed says he also had an early scare when a couple of hours after leaving their village, his sister-in-law slipped and broke an ankle.

For the next three days, Mr Saeed and his 18-year-old nephew took turns carrying her on their back. They covered the entire distance from Takhtakai to Peshawar on foot, except for two brief truck rides.

Threat to 'crucial' services

.jpg)

Those living at Jalozai have been bearing the brunt of funding cuts to the camp

Back at the Jalozai camp, the IDPs pushing wheelbarrows queue up in front of a food distribution centre to receive their monthly supplies, which have been dwindling in recent months.

"What we get is just enough for four or five days, because I have 17 mouths to feed," complains 62-year-old Abdul Hameed.

Officials at the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid (Ocha) in Islamabad admit there have been ration cuts and also a complete stoppage of reproductive health and newborn services.

This is because last year Ocha received only 76% of its $289m (£190m) appeal for funds. Officials now say they will need to bridge a $70m (£46m) funding gap to continue "crucial" services over the next year.

The provincial government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province, which chipped in with $900,000 (£590,000) of funding support last year despite a financial crunch, is afraid that adding more people to the camp population in the wake of diminishing resources may spark unrest there.

"There is donor fatigue, because this problem has gone on for several years, and there is no end in sight," says one provinical official.

Since the first large scale displacement in 2008, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's government has handled more than 298,000 IDP families, he says.

About 163,000 of them still remain displaced, living either in one of the three designated IDP camps or with what the aid fraternity call "host communities" - communities living on the fringes of the war zones that have tribal links to the displaced people.

Meanwhile, the Islamist insurgency continues to fan across the mountains, displacing more people either because of militant infighting or counter-insurgency operations by the military.