North Korea: Will new UN sanctions persuade or provoke?

- Published

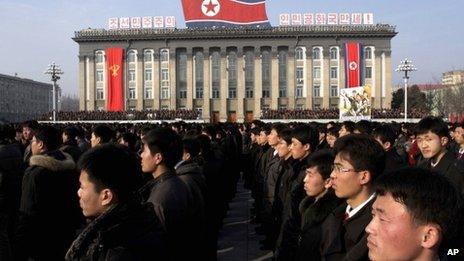

North Koreans rallied on Thursday in Pyongyang in an apparent show of support

North Korea has threatened to defend its sovereignty by launching pre-emptive nuclear strikes against both the United States and its ally, South Korea, claiming that Washington is itself preparing to attack the North with nuclear weapons.

The ostensible trigger for this warning from Pyongyang has been a two-week-long set of extensive joint military exercises involving primarily some 13,000 US and South Korean forces on the Korean peninsula, scheduled to start on 11 March.

The threat comes on the back of an earlier warning from the North to abrogate the Armistice Agreement of 1953 marking the cessation of hostilities between North Korea and the US and its allies during the Korean War.

Notwithstanding the North's strident claims that the US is planning an unprovoked assault on the North, the exercises - known as Key Resolve and Foal Eagle - are defensive in character and have been taking place routinely, in varying form, since the 1970s.

This year's exercise marks a departure only in being directed by the South Korean joint chiefs of staff rather than by the Combined Forces Command linking together US and South Korean top military officials.

A more plausible explanation for Pyongyang's bellicose, provocative rhetoric is the unanimous passage of a new UN Security Council Resolution (2094), sharply condemning North's Korea's rocket launch of December 2012 and its apparent detonation of a nuclear device on 12 February.

Historically, the North has routinely used belligerent statements when the council has been about to pass resolutions, possibly in an effort to discourage it from reaching an agreement.

Effective measure?

If blocking an agreement was the North's goal, it appears to have signally failed to achieve this.

Resolution 2094 was passed unanimously by all 15 members of the Security Council.

It significantly tightens existing sanctions intended to restrict the North's development of its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programme, while introducing a more extensive set of new measures focusing on freezing the North's financial transactions, prohibiting the opening of bank branches, limiting bulk cash transfers (a common way for the North to gain access to finance), and restricting trade connected to any of the North's illicit activities.

The resolution also targets individuals and institutions explicitly connected with the North's WMD program, strengthens interdiction measures to limit the transfer of WMD technology by land, sea and air, and also prohibits the transfer of luxury commodities - such as jewellery, yachts and cars - to the North.

While 2094 has important declaratory weight in signalling the international community's clear opposition to the North's recent provocations, it is unclear how effective the new measures will be in impeding or reversing the North's nuclear programme.

Targeting luxury commodities may impose temporary pain on the North's leaders, but it is questionable whether the list of commodities is sufficiently extensive to make a difference.

Tightening controls on the flow of cash to the North may make it more difficult for the regime to protect its assets, but the North's leadership has become more agile in eluding financial restrictions since 2005 when the US treasury successfully closed down access to some of the bank accounts of senior North Korean officials.

Most importantly, the interdiction provisions involve conditional language that could function as a loophole for non-compliance, mandating states to inspect cargo, but only if they have "reasonable grounds" to believe that cargo contains prohibited items.

The UN Security Council unanimously backed Resolution 2094

Diminishing opportunity

Pyongyang's bellicose rhetoric and its decision to close the air and sea space on its east and west coasts have heightened regional anxieties that the North may be planning to engage in some form of military provocation.

The threatened pre-emptive nuclear strike seems more bluff than reality, since the North's leaders know it would be suicidal, and an attack on the US seems impracticable given the still technically rudimentary quality of the North's ballistic missile programme and the unproven state of its nuclear miniaturisation technology needed to place a nuclear warhead atop a missile.

A more troubling possibility is that the North might choose - out of irritation with the UN - to precipitate a border clash with South Korea, either on land or sea, as it did before in 2010.

With US and South Korean forces primed to respond to any such action, there is a risk of limited conflict escalating rapidly into something far more uncontrollable and potentially destructive.

Offsetting this pessimistic prognosis is the positive sign that the North has yet to single out the new Seoul administration of President Park Geun-hye for direct rhetorical condemnation.

By contrast, in 2008, when Lee Myung-bak became president, the North was unreservedly condemnatory and critical of the new government.

With the door still open, in principle, for dialogue and diplomatic negotiation (a route that China continues to advocate), there may still be an opportunity, albeit a rapidly diminishing one, for a negotiated settlement.