Hometown Karachi: Returning to report on a bleeding city

- Published

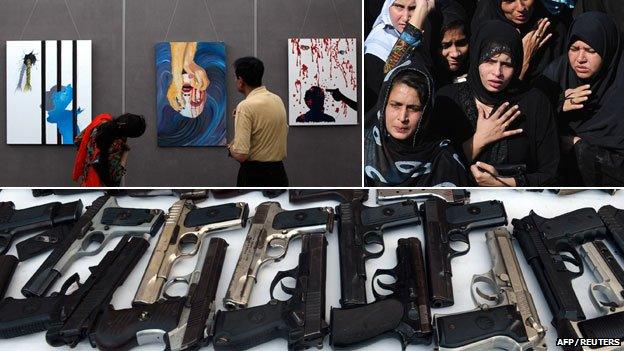

Guns and violence have become the norm in Karachi

After 12 years with the BBC World Service in London, Shahzeb Jillani has decided to return to Karachi to work as Pakistan correspondent. But, as he explains here, the turmoil in the city means his decision has not gone down very well with friends and family.

"Have you absolutely lost your mind?" That was my mother's predictable response.

"People are trying to get out of this god-forsaken city," she said, "and you are planning to come back!"

Her fears aren't entirely exaggerated. Facts speak for themselves: last year was the bloodiest year for Karachi in nearly two decades, with about 2,000 people killed in drive-by shootings, bombings, and revenge attacks.

That is based on reported figures. A lot of threats, extortion and day-to-day crime in this city of 18 million people go unreported.

But in Karachi, you can't help but hear about them in every other conversation.

Envelope with a bullet

Visiting the city recently, I caught up with friends from school over dinner at a seaside restaurant. Sitting above the splashing waves on a moonlit night, I could feel the cool breeze of the Arabian Sea on my face. We were served a large, spicy fish with a pile of hot naan bread.

There, I met a classmate, who is now an industrialist and someone I had not seen in years. When I gave him a customary hug, I felt something sticking out around his belt. He saw the puzzled look on my face, reached under his shirt and took out a gun.

"Here, it's just a 9mm pistol," he said handing me the weapon. "What are you doing with a gun?" I almost yelled at him.

"I usually don't leave home after dark. But when I do, I don't leave without it," he said. "This city has changed. It's not the same place you left 12 years ago."

Over the next couple of hours, my friends narrated incident after incident about the extent of lawlessness in Karachi.

More than 2,000 people died in bombings or other attacks in Karachi in 2012

A story about a multinational executive receiving an envelope with a bullet inside and a note saying: "Pay now, or we know which school to pick up your son from."

A story about a relative who arrived at Karachi Airport on a late night international flight, only to be abducted and robbed of his baggage while on his way home.

A story about a teenage boy shot dead along with his brother and father while he was being dropped off at school in the morning, because the family happened to be Shia Muslims.

The mood became predictably grim.

My friends tried to change the subject, joking about the stuff we indulged in as teenagers: our picnics at the beach, our failed romances and the Bollywood songs of our generation.

We talked about our cheerful friend Moin, who was the first among us to die after losing his battle with a brain tumour a few years ago.

We recalled the tears, the laughter, the embarrassments and the heated arguments, recalling the details just as we have done during previous but rare reunions.

But it was not long before the reality of today's Karachi pulled us back into the present.

A text alert informed me there had been a killing not far from where we were. A young graduate of one of Pakistan's top management schools had been killed in a drive-by shooting along with his father.

In that week alone, dozens more people in Karachi lost their lives in seemingly senseless attacks.

And yet, the chief minister of the province insisted not only that the law-and-order situation wasn't that bad, but that it was actually improving.

For most people, it sounded like little more than a bad joke. But such is the disconnect between Pakistan's rich and powerful ruling class and millions of its insecure subjects.

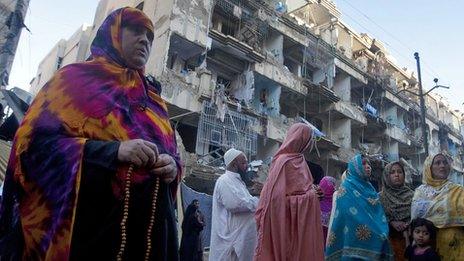

And so, Karachi continues to bleed.

City out of control?

These days, it is considered a good day in the city when "only" five to six people die in shootings. Eight to ten is considered the new "normal".

No wonder then, Pakistanis have lost track of the fact that far more people have died on the streets of Karachi at the hands of gun-toting militants and criminals in recent years, than by the much detested American drones in Pakistan's mountainous tribal areas.

And this when the city is technically not even at war - at least not yet.

So, what does the future hold for Pakistan's economic capital?

Karachi has the distinction of being home to the country's biggest number of educated, middle class people. Some of Pakistan's best universities and hospitals are located there. Nearly 60% of the nation's tax revenue come from Karachi.

But if this mega-city represents the best of Pakistan, it also presents a nightmare scenario.

Many believe - with its multi-layered conflicts and state weakness - Karachi is already out of control and ungovernable. Heavily-armed militants, al-Qaeda-linked groups and criminal gangs operate with impunity here.

Hence, the fear that the slow-burning turf war for the city's wealth, resources and votes is threatening to spiral out of control. If that happens, it could potentially destabilise this nuclear-armed country.

The optimistic view is that Karachi has seen worse periods of violence only to bounce back, even to thrive.

So far, I haven't been able to explain to family and friends why I would willingly give up my job in London and move to Pakistan. But it's a story I care about - and in my heart, it just feels like the right thing to do.

Whatever happens, I will be there reporting as the story of Pakistan's biggest city continues to unfold.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published23 March 2012