Ten things: North Korea's film industry

- Published

The army will step in to provide extras for military films

In Hollywood, North Korea is a favourite movie villain. But few know that the communist country has its own film industry, which serves as both a propaganda machine for the state and a passion project for late leader Kim Jong-il.

1. Some of the top hits were made by a South Korean

Kim Jong-il was a massive movie buff who ensured the film industry had ample funding during the 1970s and 1980s. However, he was reportedly unhappy with the quality of films produced by his countrymen.

He ordered the abduction of South Korean Shin Sang-ok in 1978, and forced the director to make films for his regime. Shin's ex-wife, actress Choi Eun-hee, was also kidnapped.

Shin's expertise as a director enabled him to make films with better entertainment and production values.

"Shin was able to use old fashioned formulas of North Korean propaganda, and turn them into great movies," Johannes Schonherr, author of North Korean Cinema: A History, says.

"He changed the quality of North Korean cinema… other North Korean films also became better under his influence."

Popular movies by Shin included Runaway, an action film that ends in a train exploding, and Pulgasari, a North Korean monster movie inspired by Japan's Godzilla.

Shin and Choi escaped during a business trip in Vienna in 1986.

Pulgasari had just been completed at that time, and Kim Jong-il did not want to admit that it had been directed by Shin, so all the credit was given to Shin's co-director, Mr Schonherr says.

Shin continued his filmmaking career in the US and South Korea until his death in 2006.

2. The worst actors were American

Many North Korean actors are said to be schooled at the Pyongyang University of Cinematic and Dramatic Arts.

But as propaganda tools, many North Korean films also required foreign characters, especially Americans, to play the villains.

"If [North Korea] needed foreigners to appear in a film, they would ask [foreigners] already living there," says Mr Schonherr.

"Pretty much everyone - foreign students, professors and sports trainers - could be asked. And people didn't usually say no."

However, they had no say in what the movies were about "and most of them were terrible actors", he says.

Some of the most well-known Americans were Charles Jenkins, Larry Abshier, Jerry Parish and James Dresnok, who all defected to the North in the 1960s.

All four starred as evil capitalists in a propaganda film series called Nameless Heroes in 1978.

Charles Jenkins later said that he had been forced to act in the films, and going to North Korea was "the stupidest thing" he had ever done.

James Dresnok, who is still thought to be in the country, is reportedly famous among North Koreans, who call him Arthur, after a well-known character he played.

.jpg)

Charles Jenkins said he was forced to act in propaganda films

3. The film will come to you

Cinemas are said to be popular, due to the limited options for evening entertainment.

"Watching movies is, or at least used to be, one of their favourite pastimes," Mr Schonherr says.

North Korean defectors he interviewed described pleasant memories of cinema-going in the 1980s and 1990s. "The cinema was where they would hang out with their friends," Mr Schonherr says.

However, North Korean films are also screened in factory complexes, collective farms and in army units, Dr Mark Morris, a lecturer at the University of Cambridge's faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern studies, says.

"It's not a matter of you buying your ticket to see your favourite film - you'd be shown a schedule of what will be screened and generally it's a good idea to show up!" he says.

A commissar would often be present at the screening, and ask people to give an evaluation of the film, Dr Morris adds.

As a result "people are very careful to read the political message of the films".

4. One message - promote the Great Leaders

North Korean films span several different genres - but they all share the same message.

"Everything goes back to promoting Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il or the party in some way," says Simon Fowler, a film critic and author of a blog on North Korean films.

In films set in the pre-Kim era, films will show "a contrast between life in the past, and life being much better [under the Kims]", Mr Fowler says.

For example The Flower Girl depicts North Korea under Japanese occupation, with its characters suffering under the oppressive rule of their landlords, who are backed by the Japanese.

Things only turn around when members of the Korean Revolutionary Army come in to overthrow the landlords, foreshadowing a better future in a North Korea "liberated" by Kim Il-sung's army.

Meanwhile, Mr Schonherr says that in martial arts films "the evil guys are always either the Japanese or the Americans."

Despite North Korea's ongoing tensions with Seoul, fellow Koreans are normally spared the villain-treatment. "If they are [South] Koreans, there's always hope, and they'll usually get educated or won over by the end of the film," Mr Schonherr says.

North Korea's first leader, Kim Il-sung, is glorified in many of the country's films

5. … But don't show them

While most films emphasise the importance of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, you will rarely see the Kims portrayed in the films themselves.

Instead, they are often portrayed indirectly.

"For example, in a war film, someone will pick up a call from Kim Il-sung giving a great military suggestion," Dr Morris says.

"Everyone will straighten their clothing when the call comes, and the General will pick up the phone as if it's a living, glowing object."

Similarly, Mr Fowler describes a scene in Marathon Runner in which the protagonist is shown running up a hill to try and catch a glimpse of Kim Jong-il's convoy.

While she misses the convoy, she is able to touch the tyre tracks his car has made.

"She is crying and overwhelmed because she's managed to touch his tyre tracks," Mr Fowler says.

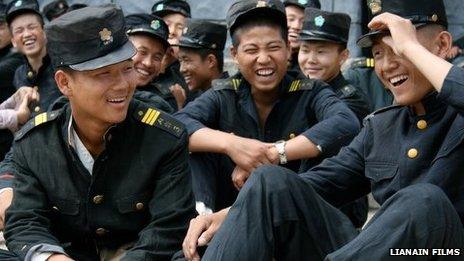

6. The army also acts

North Korea's ties with its neighbours and its bitter history with Japan, which colonised North Korea from 1910-1945, mean that epic war films are a key part of its propaganda strategy.

"Structurally, the Japanese occupation is absolutely crucial for North Korean films," Dr Morris says.

"Kim Il-sung and the Manchurian guerrilla fighters were the revolutionary faction whose identity derived from fighting the Japanese… [they argued that] fighting the Japanese earned Kim Il-sung and his colleagues the right to be the representatives of the Korean nation."

The North Korean army runs a production centre specifically for making war films, Dr Morris adds. "They provide soldiers as extras for free, as well as the necessary equipment."

Lynn Lee documented North Korea's film industry in her work The Great North Korean Picture Show.

As part of this, she was given access to the set of a war film "featuring a cast of hundreds of soldiers", directed by North Korea's Pyo Hang.

In Ms Lee's documentary, the young soldiers acting as extras are berated by Pyo Hang for not showing sufficient sadness in a scene where they are forced to surrender their weapons to the Japanese.

In the end, the director is forced to use a magic solution to make them "cry" - eye drops.

Some extras were berated for smiling or not looking sad enough during the film

7. Films feature strong women - and average men

While North Korea has always been led by men, its propaganda tends to portray strong female characters. Female athletes, soldiers, spies and even a traffic controller have featured in North Korean film.

The films show "strong, hard working women who sacrifice themselves for their leaders," Mr Schonherr says.

But while male heroes have featured in older films, especially martial arts, "there are a lot of weak men" in more recent films, he adds.

"Normally the women have to teach them how to be a good follower."

Dr Morris believes this fits in with Pyongyang's propaganda narrative. "The overarching figures in North Korea are men of the Kim family," he says.

"They don't really want rivals, so you don't have a male hero who exists in his own right as often."

And while the female characters may be strong, they ultimately know their place as well.

"Strong women [in film] generally end up having to get married - their lives are not considered complete before that," Dr Morris says.

8. Mr Bean made it into North Korea

While the media and internet are tightly controlled, foreign films occasionally make it in.

Foreign films are screened at the Pyongyang International Film Festival, which takes place once every two years. Past films include British films Mr Bean and Elizabeth: The Golden Age. Evita is thought to be the only US film screened in North Korea.

Outside the festival, it is rare for North Koreans to be offered foreign films. However, football comedy Bend it like Beckham became the first Western-made film to be shown on North Korean TV in 2010, as part of the British embassy's efforts to engage with Pyongyang.

The film was thought to be especially appropriate given North Korea's love of football, and Britain's ambassador in Pyongyang at the time, Peter Hughes, said that the film seemed well received.

9. Bikes are banned

Shots of bicycles and electric cables can fall foul of North Korea's censors

Some foreign filmmakers have been allowed into North Korea, offering an insight into how the censors think.

When filmmakers Lynn Lee and James Leong were given access to film their documentary on North Korean cinema, they had to abide by strict conditions, including allowing their footage to be shown to censors at the end of each day.

As they were chaperoned during their visit, the odds of them recording anything controversial were relatively limited. But even then, the censors came up with some surprising restrictions.

"The censors didn't like [shots of] people on bicycles or people with their shirt buttons undone," Ms Lee says. Shots including electric cabling in the streets were also banned from the film.

"I think... they wanted the city and the people to seem tidy, and not sloppy," Ms Lee says. "I can only hazard a guess because we never got to meet the censors ourselves."

10. Frame the Kims properly

Another sticking point for Ms Lee was how images of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-Il were framed.

"The censors didn't like shots that framed images of the leaders in an incomplete way," Ms Lee says. "They all had to be framed full on. If you cut off part of an image or a statue that footage would be rejected."

"This presented some problems because there were lots of images everywhere, and sometimes you don't even realise it's there when the camera is focusing on someone in front of them."

An entire section of her film, The Great North Korean Picture Show, had to be reshot, because it was set at the North Korean film museum and the images of the Kims weren't framed to the censors' liking.

- Published10 June 2013

- Published11 May 2013

- Published5 May 2013