Viewpoint: Does PNG back Australia's asylum deal?

- Published

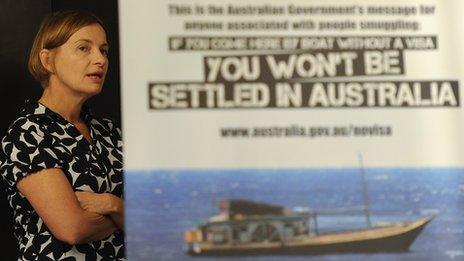

Last week several hundred students protested against the deal

Australia is to send its asylum seekers to Papua New Guinea where those found to be refugees will be resettled. But, reports Jo Chandler, the policy shift has sparked concern and some anger in the new host nation.

Effrey Dademo is a lawyer, activist and unblinkered critic of the unhappier goings-on in her homeland of Papua New Guinea. Five years ago she stuck her neck out to expose them by founding the influential online lobby community ActNOW, external!, its mission to "build a better PNG".

She is also a proud citizen, cherishing her country's vibrant traditions - it has more than 800 languages - and defending its wild, resource-rich landscapes from (mostly) foreign land-grabbers. Like many of her country-folk, she is disturbed - and deeply offended - by the implications of Australia's new hard-line asylum-seekers strategy.

Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's "PNG Solution", unveiled on 19 July, aimed to defuse a defining domestic political crisis ahead of the national election, now called for 7 September. Effective immediately, the strategy sets out to deter asylum seekers from boarding boats to Australia by promising them a new life in PNG instead - a fate worse than staying at home, apparently.

All genuine refugees identified in the next 12 months - most of them passing through PNG's expanded Manus Island processing facility - would be resettled in PNG at Australia's expense, Mr Rudd told Australian voters.

PNG's Prime Minister Peter O'Neill has been more equivocal in explaining the deal to his riled constituency in recent days. Nothing, he insists, is "written in stone", and terms would be adapted as needs be to protect PNG interests.

Ms Dademo is appalled at the commentary that Australia's "rude and discourteous" tactic has unleashed in the international media - "labelling this country as a 'hellhole', 'crime-ridden', 'impoverished' - it is simply not true".

PNG's frenetic and fiercely patriotic social media commentators were preoccupied for days debating "impoverishment" - by whose values was it measured; what account did it take of connections to clan, land, tradition?

Nonetheless the material poverty which the majority of Papua New Guinea's seven million-plus people endure is explicit. A paper published by the Lowy Institute in 2009, external estimated that about one million people live in extreme poverty, on less than $50 (£32) a year, with limited or no access to cash income, health and education services, markets, transport and food security.

Many more have insufficient or poor services. Some 85% live in rural and remote villages, surviving on their gardens; an increasing number occupy crowded urban settlements - many internally displaced by tribal or domestic violence, with no state welfare to support them.

The use of their nation as a deterrent has angered some in PNG

The health system is woeful and impossibly burdened by epidemic tuberculosis. The maternal death rate - 733 per 100,000 births - is among the highest in the world.

Roads are few and decayed; classrooms are crowded; traditional social safeguards are eroded by rollercoaster social change, and law and justice systems are too weak to stem the consequent violence. Even employed people - teachers, health workers, civil servants - struggle to find habitable housing.

"If we don't consider the already fragile state of things in-country, we're setting ourselves for disaster - although in this case, I think Australia has set us up for disaster," says Ms Dademo.

"Where do these people [refugees] live?" she asks. "Our PM was definitely sleeping when Timor-Leste rejected [former Prime Minister Julia] Gillard's use of them as the regional solution a while back. They were right. There was no proper consultation."

'Questionable handling'

The themes she identifies - lack of courtesy, of capacity and of consultation - resonate as the key concerns of opinion leaders and citizens caught up in the national conversation on the issue.

"We are an open, accepting and largely decent society and resent the suggestion that a sojourn here is something which should be portrayed as dangerous," says Lawrence Stephens, the chair of Transparency International PNG, and like Ms Dademo an activist with few illusions about PNG's problems.

Legality is another concern. A PNG opposition effort to challenge the Manus Island facility in the Supreme Court - arguing it violates a constitutional guarantee of personal liberty - stalled on a technicality but is likely to be upheld, says lawyer and prominent political commentator Deni ToKunai.

Mr O'Neill has signalled that parliament will amend the constitution to allow the deal - the latest in a series of amendments that have effectively fortified the O'Neill leadership with more than four years left to run, Mr ToKunai says.

"He's really been very smart about the whole thing… it's 90% impossible for a vote of no confidence to be put against him." Meanwhile MPs "are being bombarded about this - people are writing to them, asking what the hell is going on".

Australia has begun transferring asylum seekers to the Manus Island camp

The PNG Catholic Bishops - who have the largest congregations in the 96% Christian nation - have issued a joint statement condemning the plan as "unwise" and warning that PNG has been enlisted as "an accomplice in a very questionable handling of a human tragedy".

"While Papua New Guineans are not lacking in compassion for those in need, this country [unlike Australia which is a stable and thriving nation of immigrants] does not have the capacity at this time in its history to welcome a sizeable influx of refugees and provide for their immediate needs and a reasonable hope for a new and prosperous beginning."

Last Friday several hundred university students were turned back by armed police when they attempted to march on the Australian High Commission to protest against the deal - despite one of the sweeteners from Canberra being a windfall to reform higher education. Student leaders say it undermines PNG's sovereignty. They now hope to get a permit to regroup and rally churches and civil society groups to join them.

'Immense pressure'

Despite both the PNG national newspapers appearing to have lost interest in the topic, Mr ToKunai describes a kind of slow-burn hysteria building around the deal - "everyone is talking about it".

Inflaming the situation was confusion over the discrepancies between what was being said in Australia and PNG. Australian reports say the number of refugees to be settled is uncapped - and "but that's not what we're hearing here from our prime minister".

"On both sides of Torres Strait it is a really big issue, and our government has been under an immense amount of pressure," says Mr ToKunai. "I can't see PNG accepting more than 3,000 in total to be resettled. We may accept more than that to be processed [on Manus Island], but that is only a temporary issue."

Another festering sensitivity relates to the more than 9,000 West Papuan refugees living in PNG, many of them for more than 30 years, who are unable to access citizenship and many services or work legally .

The notion that a new intake of foreign refugees would get better treatment - because the Australian government is bankrolling their requirements under international law - than their long-suffering Melanesian brothers and sisters would distress many Papua New Guineans, Mr ToKunai says.

"Very few people have found out about that yet. And when they do, they will think it is very unfair."

Jo Chandler is an award-winning freelance journalist with more than 20 years experience at The Age newspaper in Melbourne. She has travelled extensively in Papua New Guinea.

- Published29 July 2013

- Published26 July 2013

- Published22 July 2013