Viewpoint: Where do Australia rivals stand on foreign policy?

- Published

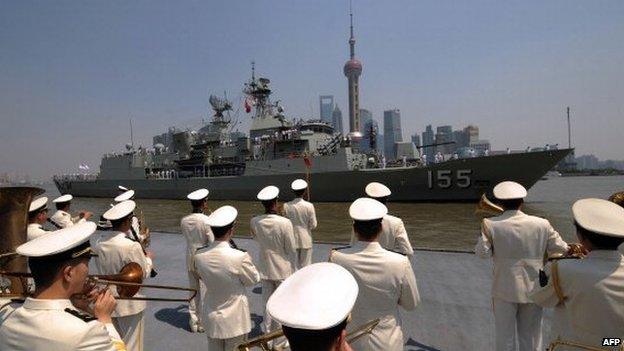

Australia's next leader must balance ties with both China and the US

Australia's election winner will need to address a broader range of global issues in a changing strategic environment, writes the Lowy Institute's Michael Fullilove, as he looks at where the poll rivals stand on foreign policy.

On 7 September, Australians go to the polls to choose their next prime minister. Labor's Kevin Rudd, serving in the job for the second time, is currently several lengths behind conservative opposition leader Tony Abbott.

There are few heads of government better versed in international issues than Mr Rudd, a Mandarin-speaking foreign-policy aficionado. Mr Abbott's background is more in the area of domestic policy and, initially at least, he would probably view foreign relations through that lens.

There are important foreign policy differences between their two political parties. At a high level, multilateralism is written more clearly into Labor's DNA than that of the conservatives. Bilateralism is more the opposition's thing, indeed it was critical of the government's successful bid for a UN Security Council seat.

Labor highlights its achievements in regional and global forums such as the Security Council and the G20, and its success in helping Australia to avoid recession during the global financial crisis. The opposition's focus is more on bilateral relationships and free trade agreements.

The opposition has signalled that it will align its foreign policies more closely with economic interests. Shadow Foreign Minister Julie Bishop promised in her remarks at the Lowy Institute foreign policy debate on 7 August that under the coalition "foreign policy will be trade policy; trade policy will be foreign policy". She stated that "aid for trade" would be a cornerstone of the coalition's aid policy.

In contrast, Foreign Minister Bob Carr warned against linking aid to trade and de-emphasising the humanitarian purpose of foreign assistance.

West or East?

There are also many foreign policy similarities between the two sides, however.

Both are exceedingly optimistic about the "Asian Century". There is shared faith in the ongoing primacy of the US alliance, confidence in the peaceful rise of China, and belief in Australia's ability to successfully negotiate its changing strategic environment.

US Marines are now based in Darwin, under a deal with Washington

Yet Australia's leading economic partner is now China - a competitor of its great strategic ally, the United States. This will pose immense challenges in the future.

On the issue of illegal immigration, the government has stated that "asylum seekers who come [to Australia] by boat will never be resettled in Australia". In an attempt to achieve this, the government has instituted a Regional Resettlement Arrangement which enables Australia to send asylum seekers to Papua New Guinea for processing and resettlement.

The opposition's policy - Operation Sovereign Borders - is for a military-led response in which decision-making is streamlined into a single command structure.

The opposition does not strictly guarantee that asylum seekers who come by boat will never be resettled in Australia. However, in another sense the opposition Leader has gone even further than such a guarantee. By promising repeatedly to "stop the boats", he has set himself a very ambitious key performance indicator should he be elected prime minister.

'Faster engagement'

The parties take a similar approach to defence spending. In recent years, defence expenditure has fallen to around 1.5% of Australia's GDP - a level not seen for three-quarters of a century.

Both sides of politics agree that it should be restored to 2% of GDP: the opposition says it will do so within a decade; the government promises only that it will do so "when fiscal circumstances allow". Neither has explained convincingly how it will hit this target.

The parties also have similar policies on Afghanistan, where 1,550 Australian Defence Force personnel remain deployed. The plan to withdraw most of these troops by the end of 2013 has bipartisan support.

For more than a decade now, Australia has underfunded its diplomatic service. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) has been hollowed out and overstretched as a result of miserly appropriations and rising demands.

Both sides agree that more should be spent on the foreign service, but they will not say how much or when.

Regardless of who wins office on 7 September, the fact is that managing Australian foreign and defence policy has become much more complicated in recent years.

The world's political and economic action has moved in our direction, in ways that are both positive and negative. Furthermore, Australia is now a member of the world's two most important economic and political forums, the G20 and the Security Council. This gives Australia a new prominence in global affairs and new opportunities to realise its prosperity and security.

All of this will test Australia as a country. Its political leaders will need to engage on a much broader range of global issues at a higher level, and at a faster pace, than they have ever done before.

For either Kevin Rudd or Tony Abbott, that test will begin on 8 September.

Michael Fullilove is the executive director of the Lowy Institute, an independent international policy think-tank based in Sydney, Australia.