Pakistan battles growing alcohol addiction

- Published

Pakistan is supposed to be officially "dry" because of its Muslim majority

Alcoholism is a growing problem in Pakistan despite it being illegal for the Muslim majority to drink. The BBC's Charles Haviland finds lives ruined and clinics and therapy groups trying to overcome a taboo subject.

Late one night, the beat of dance music drifts down from an upper storey of an apartment block on the edge of a Pakistani city.

Inside the flat, the music is pulsating around a dance floor. There is a bar where a range of liquor is being served and cocktails shaken. Under flashing stroboscopic lights, dozens of people laugh, dance and enjoy the drink.

This is one of the parties that are now commonplace in the cities but are highly discreet.

The liquor is bought illicitly from bootleggers - or from the regular alcohol shops that are supposed to sell only to minorities holding permits but also sell illegally to large numbers of Muslims.

Pakistan even has its own breweries which officially produce only for non-Muslims - or for export.

'Increasing trend'

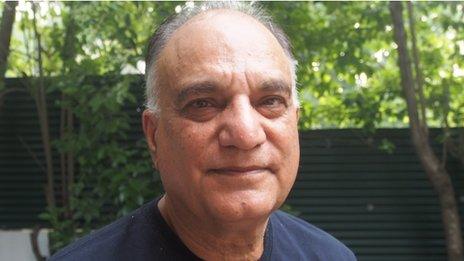

Mr Ahmed was formerly an alcoholic and now runs a rehabilitation organisation

The subculture of liquor enjoyment belies Pakistan's status as officially "dry". That is, the 96% of Pakistanis who, according to official figures are Muslim, are not supposed to drink.

The penalty if they do so is 80 lashes but it is not strictly enforced.

Although there are many harmless social gatherings, there is also a growing problem of addiction to the bottle.

Officials have told the BBC - while not wanting to be quoted - that alcohol-related diseases have risen by at least 10% in the past five years.

Tahir Ahmed, a former alcoholic who now runs a rehabilitation organisation, Therapy Works, detects "a visibly increasing trend". Six years ago, when he started this work, most drinkers were in at least their 20s; now, some are as young as 14, he says.

Sometimes alcohol is taken in conjunction with narcotics.

He says alcohol has a much firmer presence in the home - especially for the affluent - and at social occasions like weddings.

And he says that if a Pakistani drinks, it is usually in large quantities because it is, he believes, a response to the massive social pressures here, including the threat of political violence and high unemployment.

"Unfortunately drinking in Pakistan is not recreational," he said. "It's much more escapist and much more relief-seeking. That means drink till the bottle is emptied."

Now 65, this is the way he himself used to be. He watched two of his friends die of cirrhosis of the liver and nearly died himself.

He decided to stop drinking but went into clinical depression for a year. Only then did he receive therapy, later setting up his organisation, which is registered with Britain's Counselling and Psychotherapy Central Awarding Body.

'Taboo for women'

Drinking among the affluent is especially noticeable. Some senior politicians are rumoured to drink, and alcohol is served at some high-society events, though never on camera.

But it affects everybody. Last month, at least 12 people in Karachi died after drinking toxic home-made liquor.

Some Pakistani alcoholics are women. For them, the stigma is all the greater.

In Pakistan's second city, Lahore, Sara - whose name we have changed - recounts her story.

Five years ago, aged 33 and with two teenage children, she got divorced. Then alcoholism just sucked her in. She would go binge-drinking for days at a time and suffer blackouts.

"I would wake up and I would not remember the last two or three days of my life because I was so intoxicated. And that really frightened me."

Mr Umer said a strict and austere regimen helped him overcome drinking

As word got around and she became an embarrassment to her children, Sara wanted to go to a rehabilitation clinic. But being a woman made this very difficult in Pakistan.

"Some men will turn around and say, 'Okay, I have a problem.' But it's a taboo for women. A woman will never stand up and say I have a problem and I need help. That's not acceptable."

Nine months ago, she finally sought assistance and was able to get medicine and therapy-based help at home, from Therapy Works. Now she is recovering.

In an unregulated medical market, there are other clinics whose approach to treatment is much more strict. The BBC visited one in Karachi, called Willing Ways, where a group of current and former residents were in a session with the doctor who founded the establishment.

Clients are admitted with their families' consent, but they do not always realise they will be confined for three months. While living there, they are deprived of all addictive substances including tobacco, and of all external communications.

One former patient contacted the BBC and said he felt the set-up was excessively draconian.

But a satisfied former client, businessman Yousuf Umer, says the austere regimen worked for him.

"It has changed my life and I am a very successful man now."

'I'm listening'

Dr Mamsa, right, conducts a radio show using a mix of English and Urdu

While clinics and therapy-based groups tackle alcoholism, the media is now doing so too.

On Karachi's Radio 1 91 FM a psychiatrist-broadcaster, Dr Faisal Mamsa, takes calls every Thursday and Friday night on all sorts of social taboos - including this one.

"Go ahead. I'm listening," he tells callers in soft tones. Sporting a mop of unruly hair and a beard, he wears shorts in the studio.

There follows a conversation in a mix of English and Urdu.

Calls or texts from affected family members are encouraged. A woman says her husband has been drinking for 13 years but she cannot persuade him to seek help. The doctor suggests they contact Alcoholics Anonymous.

The next caller is an addict who admits he is violent.

Dr Mamsa says the anonymity of radio makes it ideal for this subject.

"I'm not concerned about the name," he said.

"If they're talking about a problem, it's not just them who's benefiting out of it but whosoever is listening to the radio is listening about it. What matters is that the problem is being discussed."

There is no chance of Pakistan's legally "dry" status changing in the near future. Yet there is an alcoholism problem, which officials and doctors say is growing.

At least more alcoholics are now coming forward to talk about it - and some are finding a way out of their misery.

- Published28 July 2013

- Published9 August 2012