Why China air zone raises risk

- Published

China says planes flying within its claimed zone must identify themselves and obey protocols

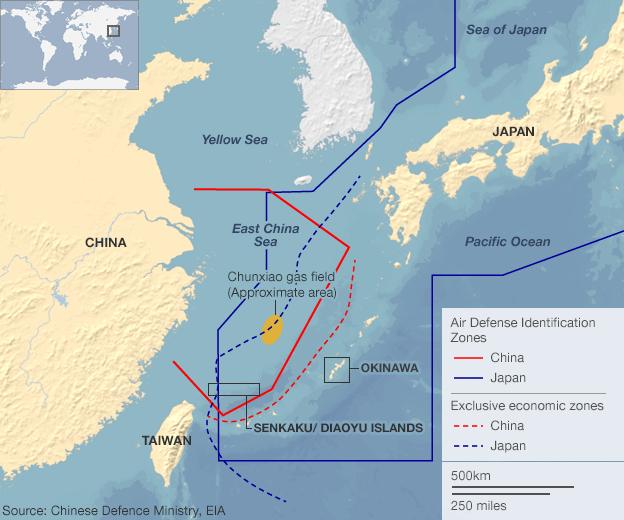

China's demarcation of an air defence zone that overlaps areas claimed by Japan is a strong statement, writes Alexander Neill of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), and one that raises the risk of possible miscalculation and escalation in the region.

China's unilateral establishment of an air defence identification zone (ADIZ) demonstrates President Xi Jinping's resolve to defend China's territorial integrity.

It is the most striking act of military escalation since he became China's top leader and top military chief one year ago.

Nevertheless, Chinese leaders will repudiate any criticism, pointing out the imposition of Japan's existing ADIZ in the region extending over China's claimed territory.

In the absence of transparency in Chinese defence spending, analysts commonly resort to the study of strategic signalling by the People's Liberation Army (PLA) - and the creation of the ADIZ amounts to a very strong signal from the military leadership.

The imposition of the ADIZ is resonant of the PLA's missile blockade of Taiwan in 1996, when former Chinese President Jiang Zemin ordered the unilateral establishment of air and maritime exclusion zones during a series of missile tests to the north and south of Taiwan.

The ADIZ declaration confirms that the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands are a "core concern" for China; it places the archipelago in the same category as the South China Sea and Taiwan.

China's defence white paper released in April holds some obvious clues to recent PLA actions. Japan is described as "making trouble" over the island dispute, while the US military pivot to Asia has created regional tension, according to the document.

Over the last decade, populist nationalism in China has been fuelled by an official narrative of humiliation at the hands of the West. Such sentiment has been tempered by adherence to Deng Xiaoping's "hide and bide" policy of strategic restraint.

Recently, however, demonstrations of Chinese military power would suggest that Xi Jinping may be prepared to overlook this policy.

China's new regional identity as an economic powerhouse with an increasingly potent military has made the humiliation narrative less relevant; a sense of national pride is now pervasive. Chinese sabre-rattling is often a reflection of domestic sentiment and a form of public appeasement.

This latest gesture comes in the wake of significant military tension in the region.

In January 2013, Japan's Ministry of Defence accused the PLA Navy of directing fire control radar onto a Japanese naval vessel not far from the disputed islands. China vehemently denies that such hostility took place.

China's best option to maintain escalation dominance in the absence of a permanent military presence in the Senkaku region is the establishment of the ADIZ.

The greatest red line for China would be the establishment of manned positions on the islands by Japan, an action which could prompt a swift escalation in hostility.

Both countries have avoided such actions thus far; however, recently China has flown drone sorties close to the disputed region, prompting fighter scrambles by Japan.

US surveillance

Another recent development was the roll-out of China's first stealth drone, which came soon after the maiden flight of the J-31 stealth fighter earlier this year.

All of these weapons systems are still in the developmental phase but they emphasise the success of Chinese military modernisation over the last decade.

And while China is far away from becoming a global military power, US defence experts have noted that China has been able to concentrate formidable military capabilities in its own backyard. Some analysts suggest that in certain areas, the PLA may be able to rival US capabilities in the region.

Most significantly, the ADIZ is symbolic of China's persistent anger at the regular surveillance and intelligence gathering sorties mounted by the US military at sea and in the air along China's borders.

One particularly sensitive episode was the loss of a Chinese fighter pilot killed in a collision with a US surveillance aircraft on an intelligence gathering mission over the South China Sea in 2001.

Chinese leaders will argue that the establishment of the zone is designed to avoid such incidents, but given the extremely fast reaction times required for air interdiction and the relative inexperience of both the Chinese and Japanese air forces, the potential for swift escalation and possible miscalculation will increase.

The proximity of the US 7th Fleet in Japan and the regular operations mounted by the US military in the ADIZ area mean that the Pentagon will be extremely resistant to comply with air identification protocols demanded on China's own terms, as will the Japanese military.

The creation of an air identification zone also belies Chinese confidence in its own command and control networks and its ability to mount air surveillance over a large expanse of the East China Sea.

The US response may be to up the tempo of its own military drills planned for the area, forcing the PLA into a defensive response, testing both Xi Jinping's resolve and his chain of command.

Alexander Neill is the Singapore-based Shangri-La Dialogue Senior Fellow for Asia-Pacific Security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies

- Published25 November 2013

- Published23 November 2013

- Published22 November 2013

- Published22 November 2013

- Published10 November 2014

- Published29 October 2013