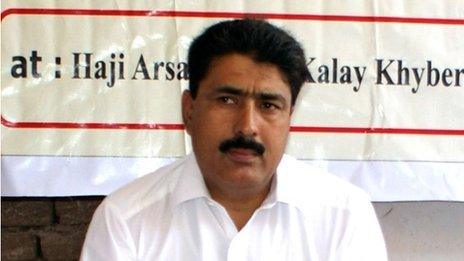

Jailed Bin Laden doctor Shakil Afridi refuses to stay silent

- Published

Shakil Afridi now faces another trial for allegedly killing a patient

The Pakistani doctor who is accused of helping the American Central Intelligence Agency track down former al-Qaeda leader, Osama Bin Laden, says he is being denied his right to a fair trial.

"I am the first individual in Pakistan to have been denied permission to meet my lawyers, which is my basic legal right," he says in a hand-written letter he was able to smuggle out to his lawyers from his prison cell this week.

"What kind of a court, what kind of justice is this?"

This is his first contact with his lawyers in 15 months. It is also his first communication with the outside world since September 2012, when he spoke to Fox News from his prison cell by a smuggled phone.

His lawyers say they are living in a communication vacuum.

Closed tribal process

"We are strategising our defence by just anticipating what our client may want, we have no permission to consult him on specific issues," says Qamar Nadeem, one of Dr Afridi's two regular legal counsels.

Besides, a very small portion of the legal proceedings against him is available in writing, says Wasim Ahmad Shah, a Peshawar-based journalist who covers legal affairs for Dawn newspaper.

"Most legal proceedings in the current phase of the case are based on verbal exchanges between lawyers and court officials, and may or may not signify actual developments in the case," he says.

"This ambiguity appears deliberate."

Bin Laden's compound was visited as part of a CIA fake vaccination programme to determine if he was linked to the property

From the start, Dr Afridi's case has carried the undertones of realpolitik instead of a legal battle.

He was arrested in May 2011 for what many ex-military defence analysts considered to be his role in organising a hepatitis vaccination campaign that aimed at procuring DNA samples from residents of a compound where Bin Laden was subsequently found.

But a year later, Dr Afridi was given 33 years in jail for a totally different offence - that of collaborating with a banned militant group operating in his native Khyber tribal region.

Few believed the credibility of that verdict, because he had actually been kidnapped by the Lashkar-e-Islam group for performing "questionable" surgeries in his private clinic in Bara, a town in Khyber region.

Locals say he paid a hefty ransom to the group to secure his release,.

Also, instead of the country's mainstream judicial system, his case was taken to an administrative court functioning under a special law governing the tribal areas, called the Frontier Crime Regulations (FCR).

These courts are presided over by officials of the tribal administration, operate behind closed doors and do not necessarily follow standard legal procedures.

It is also not clear exactly when he was handed over to the Khyber administration by the ISI intelligence service that initially arrested him on 23 May 2011.

In his Fox News interview, Dr Afridi claimed he had been kept at an ISI lockup in Islamabad for almost a year.

Convenient scapegoat

US officials have called for Dr Afridi's release

This would mean he never attended the hearings of the court, and was simply handed the sentence, which came exactly one year after his arrest, on 23 May 2012.

A temporary reprieve of sorts came in August this year when his sentence was overturned on procedural grounds and his case sent to a more senior administration official for retrial.

But last month a woman brought a murder charge against him, saying her son died after a 2005 surgery performed on him by Dr Afridi at his Bara clinic.

This has again raised eyebrows in Pakistan because hospital casualties normally fall under clauses pertaining to negligence, not murder, and relatives of a patient routinely give their consent in writing before surgeries are performed.

So what's going on with Dr Afridi?

Independent analysts are unanimous that he has served as a convenient scapegoat for the Pakistani military, which had come under severe domestic criticism for failing to prevent the American raid that killed Bin Laden.

But charging him for what he did - help lead the US to the most wanted man in the world - could cast aspersions on Pakistan's role as an ally in the war against militants.

And such a move could also preclude the possibility of Pakistan using Dr Afridi in a face-saving deal with the US at some point in the future.

But while the authorities continue to beat around the bush, Dr Afridi has refused to lie low.

He created ripples in September last year when he gave an interview to Fox News. The episode caused a blanket ban on his meetings with relatives and lawyers and cost some prison guards their jobs.

He has now smuggled out a letter to his lawyers.

"I don't know what's happening in my case," he writes. "I don't know on what grounds the commissioner suspended my sentence. But I'm happy with you [lawyers]. If you stay resolute, success is near, God willing."

- Published11 September 2012

- Published30 May 2012

- Published11 September 2012

- Published24 May 2012