What does purge say about North Korea's stability?

- Published

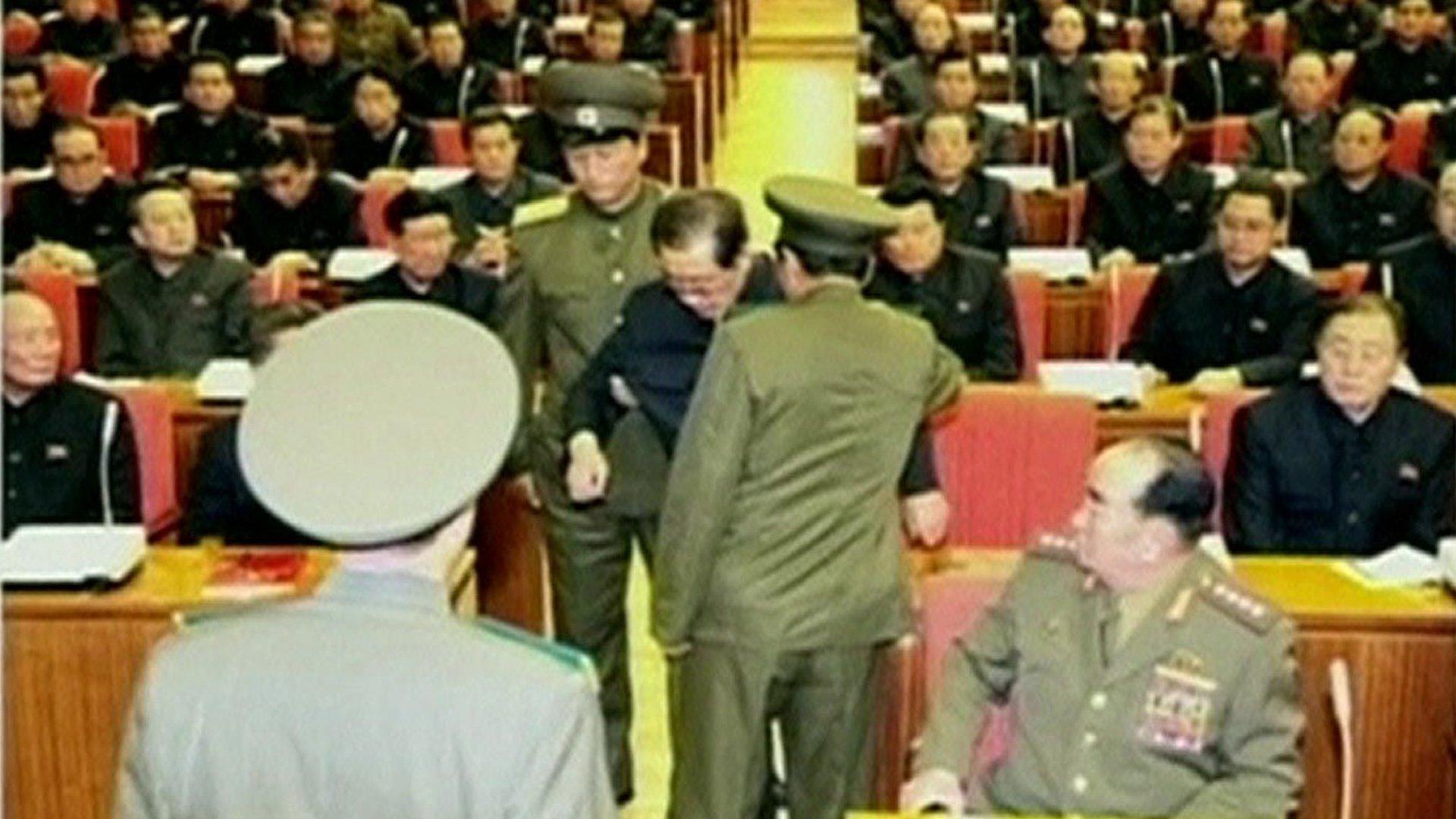

Mr Chang, second from left, outgrew his usefulness to Kim Jong-un

North Korea's second most powerful figure has been executed, days after being purged from the country's ruling elite. State media said Chang Song-thaek had pleaded guilty to challenging the leadership of Kim Jong-un and forming a rival faction within the Workers' Party. He had already been stripped of all his official positions and expelled from the party, but what does his very public expulsion say about the stability of North Korea's opaque political machine, asks the BBC's Lucy Williamson.

Few countries choreograph their political drama quite like North Korea. And after surviving for months on scraps of news and hearsay about the regime, analysts of the country's politics have been thrown a juicy steak.

Almost overnight, Chang Song-thaek morphed from uncle and mentor to North Korea's young leader to "anti-revolutionary" criminal outcast. He was stripped of all official positions, edited out of official documentary footage, and his forcible removal from a party meeting, as well as his long list of alleged misdeeds and character faults, were broadcast on state media.

The detail of those charges alone startled many people; the report on North Korea's state news agency ran to several pages.

"It's unique," an official at South Korea's Unification Ministry said. "We haven't seen this kind of official announcement in the past - the very detailed explanation seems like an attempt to provide legitimacy for its decision."

'John the Baptist'

Chief among Mr Chang's charges: that he had challenged his country's leadership, arrogated control of economic, judicial and security affairs to himself, and tried to form his own rival faction within the ruling Workers' Party.

It is the biggest political shake-up since the death of the country's former ruler Kim Jong-il two years ago. But North Korea's political reporting of itself is rarely transparent, so what might this unusual glimpse through the looking glass actually mean?

Some analysts believe it could signal restlessness within the ruling elite. As news first surfaced of Mr Chang's purge, Professor Victor Cha of Georgetown University warned that "there is a great deal more churn inside the North Korean system than is popularly depicted in the media, even though Kim appears in control".

"If you have to take out the top people," he says, "that's usually a sign that things are quite dynamic, because if they were going well, you wouldn't need to."

South Korea's online news site DailyNK, which has sources inside North Korea, believes Mr Chang's removal highlights a rift over how to boost growth in the country, perhaps sparked by China's successful economic reform process.

It quotes an unnamed source as saying that Chang Song-thaek "had been pushing for Chinese-style 'reform and opening', not a partial opening" as wanted by Kim Jong-un. "What started with conflict between the two," the source says, "ended in Chang's downfall."

Others, though, believe there is little policy difference among the top levels of government.

Dr Paik Haksoon, of Seoul's Sejong Institute, says that if divisions among Pyongyang's elite were serious, the regime would not have publicised them in this way, nor resolved them as quickly. Instead, he says, Mr Chang's expulsion is more a sign that the young Kim Jong-un has outgrown his tutor.

"Chang Song-thaek had finished his role as a bridge between the past and the future," he said. "You can compare him to John the Baptist in the Bible - the man of the Old Testament who played a bridging role for the new era of Jesus Christ."

But that role, in shepherding North Korea's young leader through the transition of power, had unexpected consequences.

Some experts see Mr Chang's removal as a sign of Kim Jong-un's growing authority

"The more people Chang attracted, the more powerful he became, and that was the challenge to Kim Jong-un," says Dr Paik. "Chang Song-thaek was such a big figure in North Korean politics that his removal demanded a long and detailed explanation on why he had to be expelled."

Even so, what is surprising, says Dr John Delury of Yonsei University, is the acknowledgement by North Korea that "there are members of the Party, and the Kim family - people at the highest levels of government - who are deeply corrupt and disloyal. This level of admission about someone who until a month ago was right next to the leader - it is startling. And also a warning to others."

Read this way, Mr Chang's removal is another sign of Kim Jong-un's authority: the latest in a series of carefully calibrated moves to demonstrate his control, and his independence - from the former army chief, whom he purged last year; from China's leaders, whom he snubbed soon after taking power; and now from his closest advisor and confidante.

And that authority is being demonstrated, not just to a domestic audience, but an international one as well.

'Important barometer'

What is striking, says John Delury, is the speed with which North Korea got control of the story. "They very quickly went public with their version of what's happened to Chang Song-thaek," he said.

"In some ways, we can link this to new developments in North Korea's relationship with the world: they have a Twitter account, they put out videos on YouTube, they're much more integrated into the global conversation, and when they become the centre of that conversation, they pro-actively get their side of the story told."

But even with such a rare level of official detail around Mr Chang's removal from power, it is never easy to pin down the truth of what is actually going on.

"North Korea's official announcements are a very important barometer for us," an official at South Korea's Unification Ministry said, "and there are certain keywords within them that we pay particular attention to. But we also have other channels - official and unofficial - that we try to gather information from."

Mr Chang used to be the second most powerful person in North Korea

Other sources, though, can be equally problematic. "The study of North Korea tends to be dominated by political organisations, governments, intelligence organisations, think-tanks," says John Delury. "And the North Korean sources themselves - whether government or defectors - tend to have very intense agendas."

He says that as a result of this lack of clear information, experts "tend to come up with a framework - you sort of have to. You start to fit facts to your framework and it becomes very hard to let go of it, and then you start missing things."

Haksoon Paik agrees that context is everything. And taking a stance - for example, by writing a newspaper column - is a risky business. "It could improve my image or destroy it!" he says. But in the end, "when there are conflicting interpretations, you have to use your judgement".

And the long years of watching North Korea's state media do gradually bestow a cumulative kind of insight, he says. One of the reasons Dr Paik believes Kim Jong-un is so firmly entrenched in his position is the experience of watching him on television, from the moment of his accession until now.

"At first he wasn't very natural," he says. "He was quite awkward sometimes. But as time passed by, he was clearly enjoying his status. I remember one occasion, a few months after he took power, when he was delivering some 'on-the-spot guidance', with Chang Song-thaek beside him. Kim Jong-un turned suddenly towards his uncle, and Chang stiffened immediately in response, just like soldiers do with their generals. It was such a natural reaction, and I was rather shocked."

Rare moments like these are perhaps the closest we'll come, at least for now, to observing directly the workings of the North Korean state. Glimpses through the curtain of North Korean propaganda; fingered lovingly like prayer-beads, year after year, by those watching from outside.

- Published9 December 2013

- Published25 September 2013

- Published3 December 2013

- Published19 July 2023