Thailand's 'red villages' eye Bangkok protests

- Published

Jonathan Head speaks to the "red villagers" still supporting Thaksin Shinawatra

The village of Nhong Huu Ling is an unremarkable rural community in north-eastern Thailand.

There are fields of vegetables, growing in the sandy soil, and clusters of fruit trees shading the houses.

Yet Nhong Huu Ling, just south-west of Udon Thani, now calls itself a "red village", as do thousands of others in the region, which is the heartland of support for the governing Pheu Thai party of Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra.

The declaration is little more than a symbolic statement of allegiance to the wider so-called red shirt movement that loosely incorporates the government's mass support base.

Villagers get together to share ideas on practical issues, like supporting small businesses or controlling illegal drug use. They also discuss politics. And these days, there is a lot to discuss.

On the day I visited the village head's house - with a giant-sized poster of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra in ceremonial robes covering one wall - there was a heated discussion about the comments being made by the anti-government protest movement in Bangkok, in particular the call for the entire Shinawatra family to be forced to leave the country - a call that at one point had reduced Ms Yingluck to tears.

The villagers were outraged by this, and were considering all changing their names to Shinawatra in solidarity.

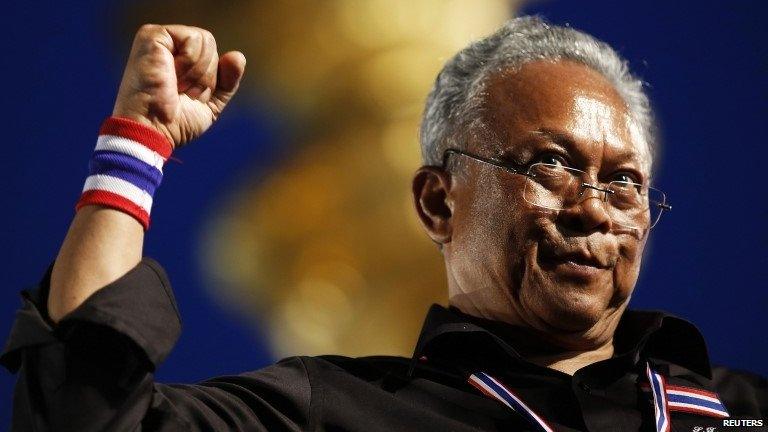

Many Thais, including villager Khamsaen Chaithep, remain fiercely loyal to Thaksin Shinawatra

They were also feeling aggrieved by the common refrain among the protesters that the people of Isaan, as the north-east is known, are too uneducated to know what they are voting for.

"Well, I know they have more education than me," said one old woman, who told me she had left school at the age of 10.

"But at least I understand what democracy is. Those people in Bangkok, who have been to university or studied overseas, how come they don't understand democracy?"

Throughout the recent crisis in Bangkok, the red shirts have been almost invisible.

That is partly because their leaders did not want to risk a confrontation with the protest movement which might prompt military intervention, and partly because their own movement has become factionalised and hard to mobilise from across rural Thailand.

People in the north-east repeatedly expressed frustration that they had to stay put, and watch the Bangkok protesters trying to overthrow the government they elected.

The loudest complaint I heard was about the allegation that the red shirts had been bought by the governing party.

Rice farmer Daoruang Sinthuwapee (front) says the rice subsidy scheme has greatly benefited his family

They were insulted by the notion that a few banknotes handed out during election time could induce them to give years of unwavering loyalty to Thaksin Shinawatra, and now his sister, Ms Yingluck.

Unprecedented help?

But what about the more sophisticated allegation that they had been bought by populist policies?

At a rice mill in Udon Thani, farmers had started queuing from the early hours of the morning to sell their harvest.

It's an annual ritual that begins with their trucks being weighed, samples of rice taken to assess moisture content, and then the sacks are opened, and the rice poured onto the growing mountains of grain stored at the mill.

In the past, they could never be sure what price they would get. Today, they are guaranteed a very generous price by the government.

Agriculture remains central to many villages in Thailand's north-east

"It means we have money left over to spend," farmer Daoruang Sinthuwapee told me. "We have enough to school our children, and more for the family. We never had this kind of help before."

But there was some uncertainty over when the farmers would be paid.

The Bank of Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives, which makes the payments, has been unable to raise enough funds on the bond market this year to cover the huge cost of the scheme.

In other parts of Thailand, farmers have started protesting over late payments.

The benefits of the rice scheme may ensure most farmers in the north-east vote for the governing party in the February election. But many economists expect the scheme to collapse, because the massive rice stocks cannot be sold on the international market for the price the government paid.

It could backfire badly on the prime minister.

Her decision to raise the minimum wage is also popular with workers. But not with factory owner Pornthep Saksujarit.

Pornthep Saksujarit's factory was squeezed by the government's decision to raise the minimum wage

He employs 400 people at his plant, making sensors and other electronic components for cars and cameras. It is the kind of investment that is helping the north-east move away from dependence on agriculture.

He told me the sudden rise in the minimum wage, to 300 Baht ($9; £6) a day, squeezed his margins to the point where he has had to stop workers from doing overtime.

"We would like help from the government, with infrastructure, or cutting taxes or the price of utilities," he said.

"But next time they want to raise the minimum wage, please do it gradually."

'Die for democracy'

The verdict on Prime Minister Yingluck's populist policies will certainly be a lot harsher than on her brother's, from his time in office, which are still widely praised, even by his opponents, and are the ones most often cited by his supporters to explain their loyalty; the low-cost healthcare scheme, and the micro-credit Village Fund.

Plern Thienyim is a passionate red shirt supporter, but she wasn't always.

"Until Thaksin came along, we always voted for the Democrat party," she told me. "Even when Thaksin was campaigning for the first time and making all these promises, we didn't believe him."

Plern Thienyim's brother, Wasan, was killed during the red shirt protests in 2010

She was working in a textile factory at the time. Then she borrowed from the Village Fund to start a small tailoring business, which she has gradually expanded. No other prime minister had ever given her an opportunity like that, she said.

So in April 2010 she and her brother Wasan joined the red shirt protests in Bangkok, against the then-Democrat government. Wasan was killed by a shot to the head in the first armed clashes with the army.

She is bitter about what she sees as the different treatment given to protesters from her side, and those now in Bangkok, and the attempts to depose the government she voted for.

That sense of injustice is driving even sceptical red shirts to stand by their party, and put aside the reservations some of them have about the continuing influence of Thaksin Shinawatra, and some of the government's policies.

"We won't accept another coup, like in the old days," said Khamsaen Chaithep, wife of the village chief in Nhong Huu Ling.

"We will fight to keep the government we elected."

"And if the military tries a coup again, we are ready to come out, to die for democracy."

- Published17 December 2013

- Published12 December 2013

- Published22 May 2014

- Published10 December 2013

- Published28 November 2013