North Korea purge: What lies ahead for Kim Jong-un?

- Published

Kim Jong-un glowered and slumped in his chair at a memorial for his father

It's a move worthy of Shakespeare: two years after he came to power, North Korea's young ruler has apparently purged and executed his own uncle for plotting a coup against him.

The brutal tale, broadcast at length on state media, had the world gripped. But how much is true? And how much has it revealed about the way North Korea's ruling family works?

Sitting on the podium beneath a giant beaming portrait of his late father, Kim Jong-un wore an expression that seemed calculated to catch attention.

Slumped in his chair, his eyes lowered and his mouth turned down, he seemed to glower at the vast court of political elites clapping before him.

He had plenty of reasons to look upset, of course. The event was to commemorate his father's death two years earlier.

But was it grief making him look so irritable, or anger at the uncle who had apparently betrayed him? Was it a warning to the assembled masses? Or even fear; a premonition that the rows of obedient acolytes hid many more such threats?

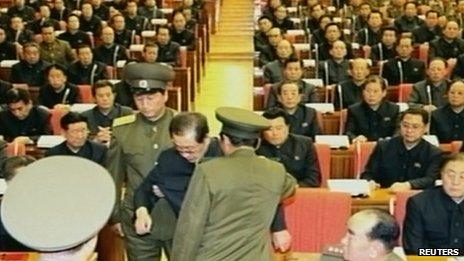

Mr Chang's purge from power was unusually high-profile

Perhaps it was even a desperate sign that the execution of Chang Song-thaek was not, after all, the nephew's doing - a signal that this 30-year-old, nuclear-armed orphan was not actually in charge of the country at all.

As usual, glimpses inside Pyongyang's political machine only seem to highlight how little we know.

The reams of news coverage churned out by North Korea give an unusual impression of instability at the heart of the North Korean regime.

They describe in lurid detail the charges being brought against Chang Song-thaek - everything from plotting a coup to using pornography to "half-hearted clapping" on Kim Jong-un's rise to power.

Photographs of Mr Chang, stooped and under arrest, were broadcast on state media. And the news was broadcast on the city subway.

But how valid are the claims that Mr Chang was plotting to overthrow his nephew?

If Mr Chang was, indeed, executed - something we have no evidence for beyond the word of the North Korean state - we can be fairly sure it was for something serious. Senior officials in Pyongyang are rarely executed, and certainly not in this very public way.

North Koreans read about Chang Song-thaek's execution at subway stations

Mr Chang was not only Kim Jong-un's mentor and guardian, he was a member of the ruling family - and the fact that two of his aides were also executed, according to South Korea's spy agency, adds to the suggestion that something serious was taking place.

But was it a coup? The level of public indoctrination following Mr Chang's arrest certainly could suggest some kind of political upheaval or threat.

Several North Koreans have reported covertly to contacts in the South that party meetings, lectures and self-examination sessions have been stepped up, and there's apparently great emphasis on loyalty.

A few days after Mr Chang's arrest, North Korea's army chief publicly vowed to "defend Kim Jong-un and no-one else".

The very fact that state media have been so expansive on the subject of Mr Chang's disloyalty is interesting, suggesting to many that something is seriously wrong at the heart of the regime.

North Korea's media are more commonly known for reports featuring the Great Leader and his visits to ever-successful factories, or ever-ready military units.

Strength or weakness?

The sudden crack in the veneer was shocking. North Koreans were told that the country's second-most senior statesman, and uncle to their leader, was a traitor; that he had peopled his many state offices with traitors, and was building a rival faction within the regime.

Many think it's weakness that drove the government to open up about this threat from within - a need to stamp out other rivals, or crush more general flickers of dissent, as economic hardship continues to bite.

It's difficult to see clearly inside Pyongyang's corridors of power, but recent footage smuggled out from the North certainly appears to show ordinary citizens shouting and standing up to policemen in the street.

Sun Mu, a former propaganda artist for the North Korean Army, told the BBC that what struck him most about the announcement of Mr Chang's arrest was the style: "The wording seemed hurried, clumsy and not really well thought out. As if it had to be expanded in an attempt to gain legitimacy."

Paik Hak-soon, of Seoul's Sejong Institute, believes that the media's new confessional spirit is a sign of the regime's strength, not weakness - and that the suggestion of serious divisions among the leadership is false.

Some analysts say Mr Chang's purge was a sign of the regime's strength

"Pyongyang would never have publicised divisions among the elite in this way if they were actually a threat," he said.

Prof Paik thinks it was simply time for Chang Song-thaek - with his reputation for arrogance and ambition - to relinquish the mentor's role; that he had become too powerful in his own right.

And there are plenty of lurid, unconfirmed rumours offering other explanations for Mr Chang's arrest - including one that ties him romantically to Kim Jong-un's wife.

Another defector in Seoul who used to work in North Korea's military propaganda unit, Kim Seong-min, said he did not believe the detailed list of charges given by state media were the real reason Mr Chang was purged.

"We knew a lot of it already," he said. "I think he must have done something that really drove Kim Jong-un mad."

Some experts believe the military is becoming increasingly prominent

So was there a coup plot? It seems a plausible explanation for why North Korea has departed from its normal behaviour over Chang Song-thaek: to use insurrection as a cover for some other crime is a risky strategy for a regime that relies on repression.

But if it is true, then given Mr Chang's prominence, the waves are likely to ripple down for many weeks to come.

Perhaps that explains Kim Jong-un's downcast expression earlier this month. But then again, there's no hard evidence that he was the one behind his uncle's execution.

North Korean analysts are divided into those who believe the young leader holds the reins of power, and those who see him as the puppet of older, more established forces - like the army.

Michael Madden, who specialises in tracking senior figures within the North Korean leadership, notes that military personnel were positioned on Kim Jong-un's right hand during a visit to the state mausoleum this month.

Kim Jong-un and his wife are standing very deliberately in front of everyone else, but both the defence minister, and the army chief of staff appear to be rising in prominence under his leadership.

And during his two years in power, there have been several instances of military aims over-riding economic ones: the closure of the industrial park at Kaesong, run jointly with the South; the cancelling of an American aid-deal with a long-range rocket launch; and the snubbing of China's influence by carrying out a third nuclear test.

Troubled times ahead?

The question of who actually wields power in North Korea is an ongoing debate.

But amid the smog of what we don't know about this incredible story, a couple of pinpricks stand out.

Mr Chang's execution shocked Koreans in both the North and South

One is the shock reported by Koreans on both sides of the border.

South Koreans expressed dismay that ancient Confucian values of respecting elder family members could be so blatantly flouted.

And several North Koreans here in Seoul reported a negative shift in attitude towards Kim Jong-un among their contacts back home, with people asking privately how their leader could do this to his uncle.

The other point of broad agreement is the likelihood of provocations to come.

The South Korean defence ministry has said it believes there's a "high chance" of military action by the North to distract attention from the troubles back home.

A senior South Korean government official, who didn't want to be named, put the likelihood at "100% - sometime before April".

Only time will tell if he's right, but if Kim Jong-un's expression is anything to go by, there may be troubled times ahead.