The search for flight MH370

- Published

The hunt for Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 enters a new phase in September, as investigators intensify their search of a refined area of about 60,000 sq km.

This refined search area is located 1,800km (1,100 miles) off the west coast of the Australian city of Perth.

Using specialist equipment to survey the ocean floor, teams searching for wreckage of the plane have been mapping the sea bed.

Until now, knowledge of this part of the ocean floor was limited, but the mapping will allow targeted searches to take place.

Six months on from the disappearance of the plane, which was carrying 239 people en route from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing, its fate remains a mystery.

No trace of the aircraft has been found and there is no explanation for its disappearance.

In May, the initial hopes that acoustic signals thought to be from MH370's "black box" flight recorders would lead investigators to the jet's final resting place were dashed.

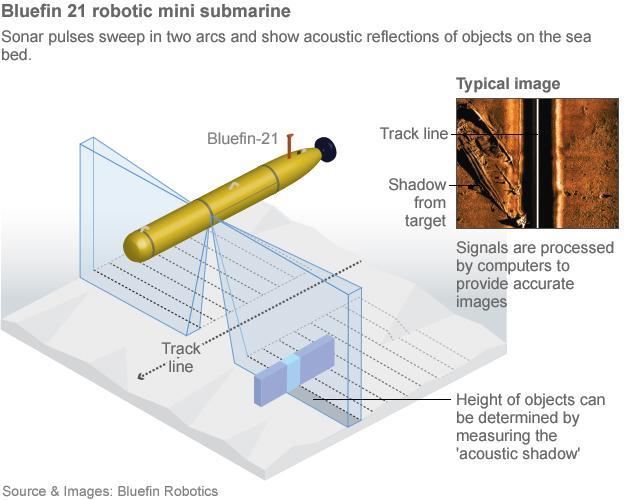

Australian officials said that a Bluefin-21 submersible robot found nothing in its search of the area where four "pings" were detected in April.

The new phase of the search, in which contracted ships fitted with specialist deep tow survey systems will conduct a metre-by-metre for the missing plane, is expected to start by the end of September and may take up to twelve months.

Where is the search?

Since the plane disappeared on 8 March, the hunt has changed in scope many times, starting in the South China Sea.

At its largest, it covered 7.68 million sq km (2.96 million sq miles) - a total of 2.24 million square nautical miles. This was the equivalent of 11% of the Indian Ocean and 1.5% of the surface of the Earth.

However, from 16 March, satellite images of possible debris and tracking data released by the Malaysian authorities appeared to confirm that the plane crashed in the Indian Ocean, south west of Australia.

After searching an area more than 2,000km (1,240 miles) south-west of Perth, the hunt switched more than 1,000km (600 miles) further north, based on further analysis of radar data which showed the plane was going faster, thus using fuel more quickly.

The search zone narrowed again in early April to an area of 850 sq km (328 sq miles) of the ocean floor - located close to acoustic signals detected by Australian teams.

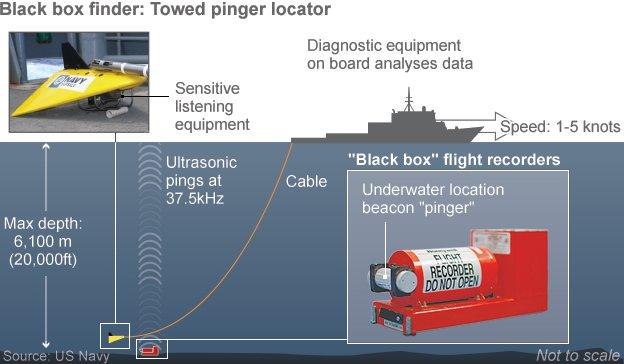

Richard Westcott reports on the use of a pinger locator to find a black box

But after the area where the 'pings' thought linked to the missing Malaysian plane were detected was ruled out, efforts turned to reviewing search data and surveying the sea floor using specialist equipment.

This further analysis of satellite data resulted in identifying a new search area announced in June, shifting the focus to an area 1,800km (1,100 miles) off Perth.

This area's sea bed is being mapped by the Chinese survey ship Zhu Kezhen, which was joined in June by the Dutch-owned Fugro Equator vessel.

The survey is expected to yield detailed information about the shape of the ocean floor, considered essential to the search for the missing plane.

Without the mapping phase, it would not be safe to put down submersibles to conduct a metre-by-metre search, as there is a high risk these vehicles would be lost.

The mission is expected to take up to a year, at an estimated cost of $55m (£34m) or more.

Authorities have also asked the UN's Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization to check its system of hydrophones, which are designed to pick up possible nuclear tests, for any clues as to where the aircraft may have crashed.

Who has been taking part in the search?

Eight countries have been assisting - Australia, China, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The investigation is being led by the Malaysian authorities, who are also liaising with the FBI, Interpol and other international law enforcement agencies.

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) is leading the underwater search for missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370.

The day-to-day search operations have been run from Australia's newly-created Joint Agency Co-ordination Centre, external (Jacc) based in Perth.

Dutch firm Fugo Survey, external has been contracted by the Australian government to conduct the deep sea search, using its vessels to search a swathe of the Indian Ocean where the plane is believed to be located.

Members of China's Civil Aviation Administration and officials from the France's Office of Investigations and Analysis for the Safety of Civil Aviation have also been involved in the investigation.

The French have been lending expertise from the two-year search for the flight recorders from the Air France Airbus A330 which crashed into the Atlantic Ocean in 2009.

British company Inmarsat, along with the UK Air Accident Investigations Branch, have provided detailed satellite data analysis to aid the hunt.

What key equipment has been used?

Two vessels - the Australian naval support ship Ocean Shield and the UK's HMS Echo - used specialist listening equipment that can detect ultrasonic "pings" from the plane's "black box" flight recorders.

The Ocean Shield used a "towed pinger locator" (TPL), which is pulled underwater behind the ship at slow speeds and uses a highly sensitive listening device called a hydrophone to pick up signals.

Once the "pings" were detected, the autonomous mini-submarine Bluefin-21 was despatched to create a detailed sonar map of the sea bed. It is also able to carry a camera unit to take pictures of any possible wreckage.

By 29 May, it had scoured 850 sq km (328 sq miles) of the ocean floor, Australia's Joint Agency Co-ordination Centre said.

The depth of the water in the search area is estimated to be between 2,000m and 4,000m (6,560ft and 13,120ft).

Early in the search, military aircraft also scoured the area for any possible floating debris.

Aircraft types involved in the search include a US Navy P-8 Poseidon and Australian, New Zealand, South Korean and Japanese P-3 Orion maritime surveillance planes.

Two Chinese Ilyushin Il-76s also operated out of RAAF Pearce air base near Perth, while Malaysia sent two C-130 Hercules aircraft.

The Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion is equipped with radar and infrared sensors as well as observation posts to help detect any debris on the surface of the ocean. It also has three cameras beneath the landing gear capable of zooming in for a closer look.

The four-engine turboprop plane is designed to fly low and slow to aid surveillance. Once it has reached the search location, one or two outer engines can be turned off to preserve fuel and extend the surveillance time.

The plane is also fitted with a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) - used for detecting submarines underwater. The aircraft also has acoustic detectors, which are able to detect sound 1,000ft (304.8m) below the surface of the ocean.

Australia's HMAS Success, a naval oil tanker, is equipped with a crane which could be used to recover any possible wreckage.

China has deployed a number of vessels, among them the survey ship Zhu Kezhen, external, in the area where the plane is thought to have crashed.

The Equator and a second ship, the Fugro Discovery, will use deep-tow instruments

Its operations are being supported by the Chinese ship Haixun 01 and Malaysian vessel Bunga Mas 6, which are helping transport data to Fremantle each week for further processingwe.

The UK's HMS Tireless submarine, described as having "advanced underwater search capability", also joined the team.

Starting late September, the Fugro Equator and Fugro Discovery vessels will use side-scan sonar, multi-beam echo sounders and video cameras to hopefully locate and identify the aircraft debris.