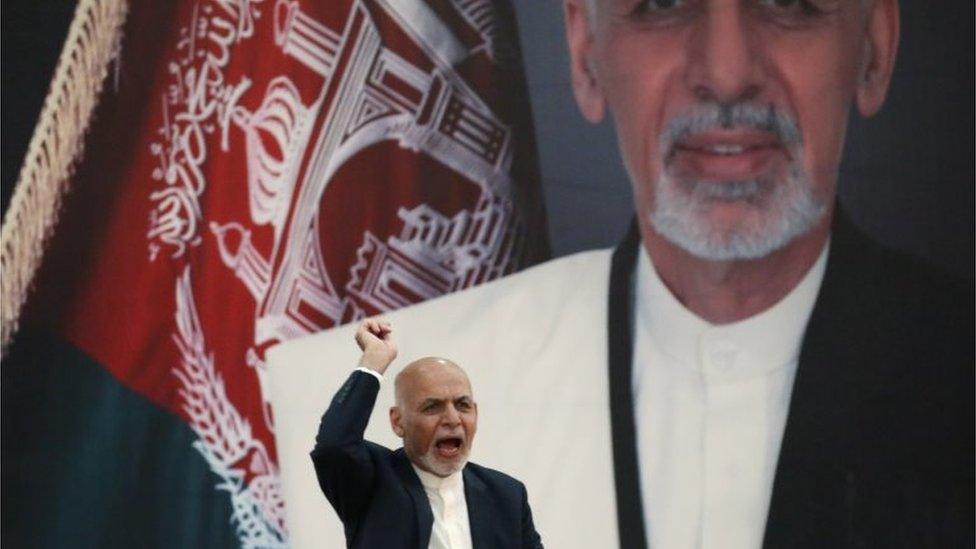

Who is Ashraf Ghani? The technocrat who sought to rebuild Afghanistan

- Published

Ashraf Ghani gave up his US citizenship to stand in the 2009 Afghan presidential election

Ashraf Ghani is a former technocrat who spent much of his career outside Afghanistan, before returning to help the country rebuild after years of war.

He came into office in 2014 seen as incorruptible and hands-on - too much so, some would say - but is also noted for his short temper.

However, five years later, with memories of the fraud allegations which mired the 2014 vote still fresh in Afghans' minds, his reputation stands a little more tarnished.

Mr Ghani's time in office has been marked by an uneasy alliance with his chief executive and main rival for the top job, Abdullah Abdullah.

A member of the country's majority Pashtun community, Mr Ghani took office as most foreign troops were leaving in 2014.

But since then the Taliban have extended their presence, eroding Kabul's writ across the country - undermining Mr Ghani's authority.

He was shut out of peace talks between the US and the Taliban, before they were called off earlier this month. The militants regard his government as US puppets.

Mr Ghani has introduced some anti-corruption policies but little progress appears to have been made. Earlier in September, the US said it would withdraw about $100m (£80m) earmarked for an energy project, citing unacceptably high levels of corruption in the Afghan government.

Afghan government 'cannot be sidelined'

Ashraf Ghani first came to prominence in Afghanistan running the loya jirga - the grand meeting of elders after the fall of the Taliban in 2001.

He had previously been an academic in the US, and worked for the World Bank.

As a close ally of then-President Hamid Karzai, he was made finance minister in 2002, working alongside his future opponent Dr Abdullah Abdullah, who was foreign minister in the same administration.

After he fell out with President Karzai in 2004, he was appointed Chancellor of Kabul University, where he was seen as an effective reformer.

He was also a vocal critic of the way international aid money was being wasted in Afghanistan, and, in particular, money from the US, which he saw as operating in a "parallel state" which hired the best Afghans to service foreign offices in the capital Kabul, rather than building effective Afghan institutions.

In a BBC interview in 2007, he said: "When we build a school by Afghans, the maximum cost is about $50,000. But when it is built by our international partners the cost can be as high as $250,000."

The difference was caused by the fact that contractors, many of them foreign, took percentages. He said: "It's totally legal, but is it not corrupt?"

However, he had little political support in Afghanistan at the time. In 2009, he ran an ineffective campaign to be president and came a poor fourth in a race that was again won by President Karzai.

But with Mr Karzai barred by the constitution from standing for a third time, Mr Ghani mounted a second, far better campaign in 2014. He built a solid base of support after raising his profile in province after province as the head of the team managing the transition of military control from the US-led coalition to Afghan forces.

Abdullah Abdullah and Ashraf Ghani signed a power-sharing deal but have been at odds

Mr Ghani eventually emerged as president after the US mediated a deal with Dr Abdullah the same year. The protracted negotiations did nothing to foster trust between the two men.

And while his campaign was far better organised in 2014 than 2009, his victory was tarnished by the discovery of far more fraudulent votes on his side than for Dr Abdullah.

Mr Ghani also tarnished his international reputation as a clean technocrat by his choice of running mate - General Abdul Rashid Dostum, a leader from the north with a notorious past.

In a newspaper article during his 2009 campaign, Mr Ghani had called him a "known killer". The alliance which followed five years later was a pragmatic decision that delivered votes in places where the future president had no profile.

This time round his choice of running mates appeared less risky.

- Published5 October 2017

- Published6 June 2017