Why are climbers leaving Everest?

- Published

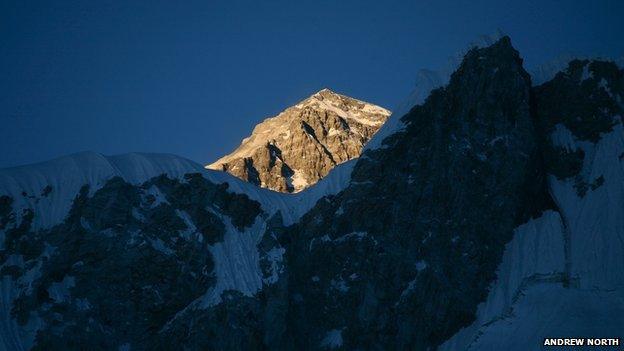

Mount Everest, the world's highest peak standing at 8,848m (29,029ft), straddles Nepal and China

The climbing season at Mount Everest is in disarray after 16 guides were killed in an avalanche, prompting a row over the risks they take and how much they are paid.

Why are climbers leaving Everest?

An avalanche killed 16 Sherpa mountain guides on 18 April, the beginning of Everest's annual three-month climbing season.

The tragedy shocked climbers and sparked a row over Sherpas' conditions in relation to the much greater risks they take. Despite an attempt by the Nepalese government to mediate, many Sherpas refused to carry on helping expeditions climb the mountain, prompting large numbers of foreign mountaineers to descend.

Many are characterising this as a labour dispute, with a new, younger generation of Sherpas demanding better rights than their predecessors.

What happened on 18 April?

An avalanche struck the area known as the Khumbu Icefall, just above base camp, as a group of more than 20 Sherpas were making their way through this twisting mass of ice-boulders and crevasses.

The Khumbu Icefall is just above base camp at 5,800m (19,000ft)

They were working for several different climbing expeditions, including the British company Jagged Globe, and carrying loads to camps higher up the mountain.

The avalanche killed 13 Sherpas and left three missing presumed dead.

It was the single deadliest accident on the mountain.

Surendra Phuyal, in Kathmandu, reports on the deadly avalanche

What happened next?

Climbing teams started leaving the mountain for the following reasons:

Labour dispute - Sherpas refused to re-fix the route as part of their stand. Many companies were still prepared to climb, but it became impossible amid the dispute

Compensation and pay row - the government initially offered $400 (£238) compensation to victims' families, sparking protests and threats of a boycott. It later revised its offer to $5,000 but families want $10,000. There has also been conflict over Sherpas' pay - which is dwarfed by government revenue from climbing permits

Respect for the dead - the Sherpas, and some climbers, urged that summit attempts be suspended following the tragedy

Being able to return - some climbers were influenced by government assurances their climbing permits would remain valid for the next five years

The families of the dead Sherpas are demanding higher compensation from the government

Will anyone climb Everest this year?

As of mid-April, about 300 international climbers were at base camp. Of 50 teams there, 31 intended to climb Everest. About half are leaving or preparing to leave. Sherpas, who make up a similar number - are also leaving, along with hundreds of other support staff such as cooks and porters.

Ang Tshering Sherpa, president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association, says it is possible no-one will climb the mountain this year.

"Teams are leaving, it's over for all," says climber Alan Arnette, on his blog., external "Time to mourn and regroup."

Meetings have been held at base camp between the government and Sherpa guides

But Madhusudan Burlakoti, a tourism ministry official, says he hopes some teams might still climb.

Navin Singh Khadka, of the BBC's Nepali service, says the government and mountaineering bodies will do all they can to avoid any closure of the mountain.

The official line from the government is stay and climb, or leave - it's up to you, he says.

But meanwhile several climbing teams are making their preparations to climb the mountain from the Chinese side and are reportedly on schedule.

Has anything like this happened before?

Khadka says the scale of the crisis is without precedent.

Some teams left following the 1996 disaster in which eight climbers died during a storm and in 2006 following controversy after a solo climber died.

In total, some 250 climbers have died on the mountain.

What is the future for Everest?

The world's highest peak has seen controversy several times in recent years. Overcrowding and environmental damage - as well as safety concerns - have been among the issues stirring headlines.

But the mountain continues to attract hundreds of climbers each year, and Khadka says Sherpas, who can earn up to $8,000 (£4,800) in the three-month Everest season - 10 times the national average wage - will always need to make a living.

Everest has continued to fascinate since the first summit attempt in the 1920s

It's been a black year for Nepalese mountaineering, says Khadka, but high unemployment means guides have no choice but to return.

As long as the mountain is there, people will climb it, he says, and officials say the current crisis is gifting them an opportunity to look at these wider issues and how to manage them.