Vietnam border shoot-out raises Uighur questions

- Published

Thai border authorities have detained several Uighurs from Xinjiang, China, in recent months

Last weekend Thai authorities said they had arrested a group of 16 suspected illegal migrants thought to be Uighurs from Xinjiang, China.

The arrests came days after a violent incident on the border between Vietnam and China in which seven people died. The 16 Chinese nationals involved in this clash were also believed to be Uighurs.

These events show South East Asia may have become a transit hub for Uighurs leaving China.

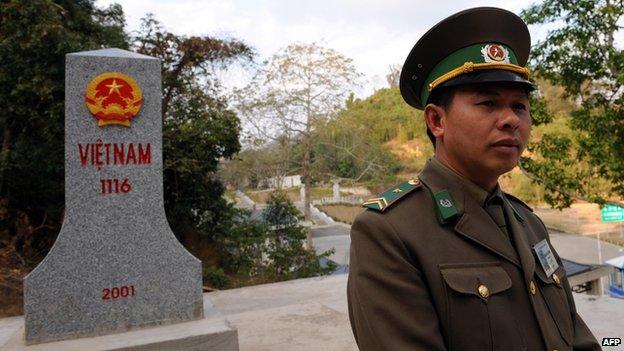

Bac Phong Sinh is a remote border crossing nestled in the hills between Vietnam's Quang Ninh province and China's Guangxi.

It awakes for only a few hours a day when Vietnamese and Chinese traders pull through their carts, loaded with fruits, vegetables, garments and other consumer goods.

What happened in the afternoon on 18 April was unexpected. A group of 16 Chinese nationals - 10 men, four women and two small children - had been brought to Bac Phong Sinh that morning after being detained for "illegally entering" Vietnam.

The Quang Ninh border guard said that while waiting to be transferred back to China, some of the men began attacking the guards, armed with wooden bars that they had broken off the furniture inside the interview room.

They also seized an AK-47 automatic rifle from one of the guards and opened fire, Colonel Le Tien Thanh told reporters.

Vietnamese soldiers from nearby border posts and policemen were sent in to deal with the incident. In a fight that lasted more than three hours, two Vietnamese border guards were killed. Five Chinese nationals also died - some shot dead and others killing themselves by jumping from the tall building, according to local media.

Newspapers reported that the Vietnamese quickly transferred the bodies, together with the remaining migrants, some injured, to the waiting Chinese special forces.

The local government then issued a statement saying the situation was under control and everything had returned to normal. They also praised the courage of the Vietnamese soldiers who "gave their lives to defend the country's sovereignty".

Uighur groups accuse the Chinese government of religious and cultural repression

'Not appropriate'

But many questions are left unanswered.

Tran Quoc Thuan, a former official at Vietnam's National Assembly and a lawyer, asked about the "unusually fast transfer of bodies and people to the Chinese side".

Unverified photos posted on Vietnam's social media showing bodies being stacked on a cart led to criticism of "inhuman treatment" by the authorities.

"It is not normal [for the Vietnamese] to transfer them across the border without any investigation even after they allegedly killed Vietnamese border guards," Mr Thuan said.

"There is also a possibility that the [Chinese] side will give them [the injured people who were repatriated] the harshest punishment."

Mr Thuan suggested it was possible Vietnam and China had reached a deal on how to handle this kind of case. But he said what had taken place was "not appropriate to Vietnam's laws and international legal practices".

In 2009 Vietnam and China signed a pact on land border management, in which both agreed to co-operate to "prevent and stop illegal migration" across the border.

Vietnam and China agreed on a land border management deal in 2009

Vietnamese press, quick to cover the shoot-out in Bac Phong Sinh, have swiftly removed references to Xinjiang in their reports. Photos of four women in the group, all wearing headscarves and distinctive Uighur clothing, were also deleted from official media websites.

It seems, say observers, to be a concerted effort to describe the Chinese nationals as "illegal migrants" and take out any ethnic and possibly political connotation.

Uighurs live predominantly in western China and are mostly Muslim. Uighur groups accuse the Chinese government of religious and cultural repression.

There have been several violent incidents in Xinjiang, including ethnic rioting in Urumqi in 2009 that killed 200 people.

More recently there have been high-profile attacks in Tiananmen Square and at Kunming railway station that the Chinese government has blamed on Uighur "terrorists" inspired by extremist groups.

Rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch warn that this would "likely contribute to an increased outflow of Uighurs from China".

Vietnam is one of the chosen routes as Chinese nationals do not need a passport to cross the border, just a travel permit - which is easy to obtain.

In the evening on the same day, 18 April, another group of 21 suspected Uighurs was said to be detained in Mong Cai, not far from the location of the shooting.

'Investigation needed'

Vietnamese media from time to time report on arrests and repatriations of groups of "illegal migrants who said they'd travelled from Xinjiang via Yunnan to Vietnam", but the number of Uighurs using this route is unknown.

Carlyle Thayer, a veteran Vietnam watcher in Canberra, Australia, said: "Vietnam appears to be under pressure from China to detain and repatriate Uighur asylum seekers who attempt to enter Vietnam as a gateway to resettlement overseas, in Turkey for example."

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has operated an office in Hanoi for decades but so far it has not received any Uighur refugee applications.

Beijing blames Uighur "terrorists" for the attack on Kunming railway station in March

Vietnam, as well as some other countries in the region, does not have a national asylum system nor has it signed the UN 1951 Refugee Convention.

Potential refugees are normally regarded as illegal migrants and this, say rights groups, makes them susceptible to detention, expulsion and other risks.

But Peter Showler, a Canadian refugee law expert, argued that as "Vietnam is not a signatory to the convention it is therefore not bound by its obligations".

"Each sovereign country has the right to decide which non-citizens can enter and remain in its territory," he said. "The starting point is sovereignty."

Vietnam also does not wish to repeat the experience it previously had with North Korean refugees.

For years Hanoi turned a blind eye to not only the border crossings but also the presence of safe houses for North Korean defectors in the country, risking seriously damaging the relationship with Pyongyang, its traditional ally.

After the airlift of more than 450 North Koreans from Vietnam to Seoul in July 2004, the Vietnamese government tightened border controls in order to make sure this awkward situation would not happen again.

Meanwhile, the exile World Uyghur Congress has called on the UN to look into the border shooting.

Spokesman Dilxat Raxit told the BBC Chinese Service: "We urgently urge the United Nations to investigate the action by the Vietnamese authorities that resulted in the deaths of the Uighur people".

- Published26 September 2014

- Published3 March 2014

- Published3 March 2014