Why ISI spy posters are all over Islamabad

- Published

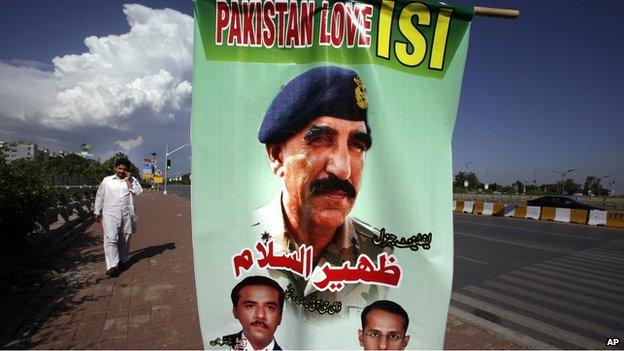

It looks like an election poster - but the man in the frame is ISI chief Zaheerul Islam

The banners and posters that went up on the central avenues of Pakistan's capital, Islamabad, over the weekend have the aura of a political campaign.

But there are no elections in sight, the banners do not praise any political party, and the face painted on most of them is not that of a politician but of the once secretive ISI intelligence chief, Lt Gen Zaheerul Islam.

"We love [the] Pakistan army and the ISI, and condemn attempts to malign them," reads the message on the banners.

Bizarre as it may sound, the campaign is apparently a public response to recent accusations by Pakistan's largest media conglomerate, the Jang group, that one of the top presenters of its Geo television channel might have been attacked by the ISI.

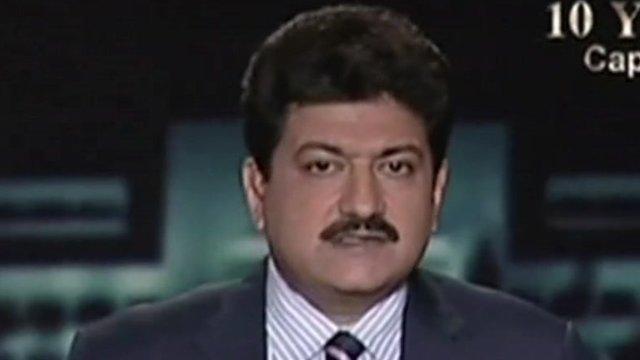

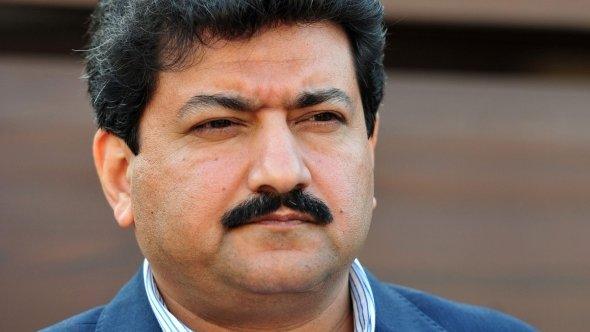

Hamid Mir survived a gun attack in Karachi on 19 April and is recovering in hospital.

Soon after the attack, his brother, Amir Mir, who is also a journalist, said in a statement that the TV anchor had earlier expressed fears the ISI might try to kill him.

Geo ran this statement for several hours against the backdrop of Gen Islam's picture - a move that many interpreted as an indictment of the general before an investigation could prove him or the ISI guilty.

The posters line central streets in the capital

Army chief Raheel Sharif (right) also figures prominently in the banners and placards

It was also unprecedented. While the role of the ISI has figured in public discourse in recent years, it has never been directly accused of any wrongdoing.

'Media trial'

But this troubling new precedent and its aftermath also brought on a feeling of deja vu.

The groups that have taken to the streets to express their love for the army and the ISI are more or less the same ones which defended the two institutions when Osama Bin Laden was found and killed in Pakistan.

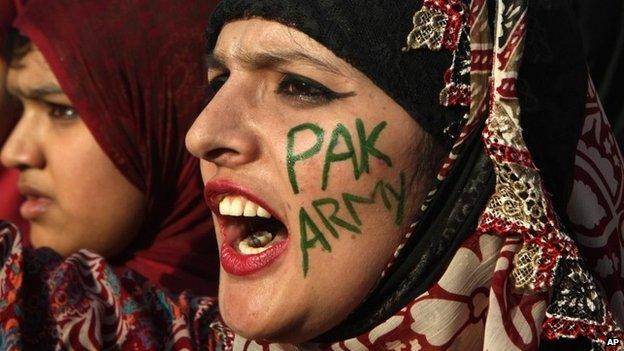

Campaigners have taken to the streets to defend the army

Later that year, they ran a vociferous street campaign aimed at preventing the last civilian government from reopening the Nato supply routes that Islamabad had ordered closed following an American air raid on one of its border posts.

Also, it is not the first time that Geo has been accused of wilfully confusing opinion with facts to hold what many call a "media trial" of public figures.

During the last five years, Geo was repeatedly accused of painting former President Asif Ali Zardari and his Pakistan People's Party as corrupt, even though none of them had been convicted by a court.

The trend proved infectious and was adopted by rival television channels in their race for public ratings and revenue.

Many suspect the ISI actively supported this trend and often offered lopsided information to certain presenters with a view to keeping the civilian government under pressure.

Many say both the ISI and Geo have become victims of their own "over-indulgence". Geo tried to conduct a "media trial" of the ISI, and was in turn accused of being an agent of hostile foreign powers by rival television channels vying for a share of Geo's mammoth business interests.

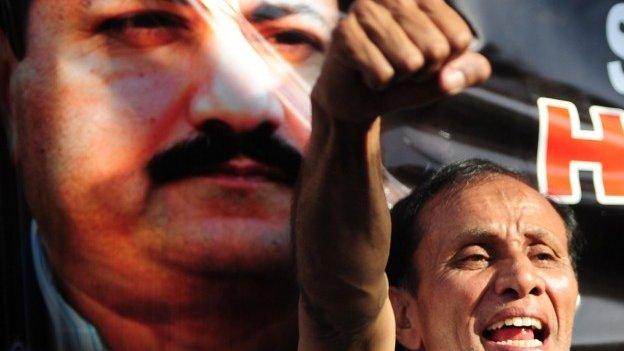

Human rights activists have staged protests against the Hamid Mir attack...

On the ISI's part, too, it is not the first time it has been suspected of carrying out an attack on journalists. In a number of cases since 2006, it has been accused, albeit indirectly, of intimidating, threatening, kidnapping or even killing journalists.

Run under standard operating procedures because there is no specific legislation to regulate its affairs, the ISI is known to have arrogated to itself a monopoly over shaping the country's security paradigm, and creating the social narrative to support it.

The proliferation of militant groups - and their respective political wings that are occasionally seen on the streets - are said to be a product of this autonomy.

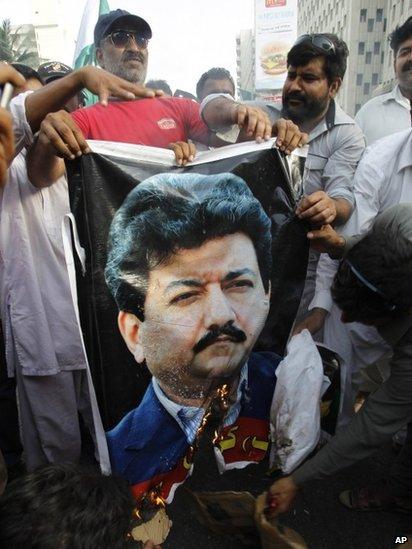

... army supporters burned a poster of Mr Mir

During the 1990s, the intelligence operatives indirectly controlled the narrative, promoting it mainly through the Urdu language press. Today they are known to directly influence the material that runs on TV channels.

Talk-show hosts from across the Pakistani electronic media have often privately shared anecdotes of how frequently ISI officials float programme ideas to producers and presenters, suggest subjects for talk shows, and set up unofficial moles of ex-servicemen and journalists to influence the debate.

Three-way battle

Both the intelligence establishment and the main media houses have tended to be on the conservative side of the social spectrum, providing a disproportionate space to hard-line religious groups and militants.

But signs of a rift emerged between them following the 2007 lawyers' movement that forced the military government of Pervez Musharraf to reinstate the country's chief justice it had sacked months earlier.

A major part of that battle was fought on television screens, with the journalist community pitting itself against the then military ruler.

Since then, the media has been growing in power, and has tried to wade into areas that were traditionally an exclusive domain of the ISI.

Hamid Mir's Capital Talk - one of the most viewed prime-time shows on current affairs - came up with some of the most biting criticism of the military's role in Balochistan, where locals accuse the ISI and its surrogate groups of kidnapping and sometimes killing political activists suspected of ties to a separatist insurgency.

Mr Mir also expressed mostly anti-military views on the issue of whether or not the former President and army chief, Pervez Musharraf, should be tried for high treason.

The military has had reservations over this move because it fears that Gen Musharraf's trial will show the institution in a negative light.

While the government has gone ahead with bringing a treason case against Gen Musharraf, the current army chief recently vowed to "resolutely preserve [the army's] dignity".

The attack on Hamid Mir is seen as an added trigger in a three-way battle of one-upmanship among the soldiers, the politicians and the media.

- Published23 April 2014

- Published25 April 2014

- Published27 April 2014

- Published27 November 2012

- Published15 March 2024